Social Classes in France, 1815-1870

Gordon Wright, France in Modern Times: From the Enlightenment to the Present (New York: W.W. Norton,1981), pp.167-170.

"The paradox of French history is that a revolutionary settlement was to provide the basis for a profoundly conservative pattern of society." -- Alfred Cobban

Juridically speaking, France emerged from the revolutionary era a society of atomized equals, with no intermediate groups intervening between the whole society and its individual citizens. In reality, it remained a complex tapestry of classes, groups, and professions, the outlines of which are difficult to distinguish clearly. Many of France's prerevolutionary social distinctions survived in custom if not in law; and superimposed upon them were new distinctions of more strictly economic character. The diversity thus produced was still further increased by persistent regional differences in speech, culture, and outlook. Although the revolution had swept away many artificial barriers to national unity and had intensified the sentiment of nationalism, several generations would still be needed to erode away deeply etched provincial traits. Indeed, that process of erosion has never been completed to this day. Restored to the top of the social pyramid in 1814 was the old aristocratic caste, undiminished in its pride of birth though no longer privileged in a legal sense. . . . The old court aristocracy did face serious problems of readjustment, notably of an economic nature. Most of them had lost their prewar estates and -- more serious still- -- the royal subsidies that had once supported them in frivolous leisure at Versailles. They hiked to the public treasury for help; what they sought was either compensation for lost properties or some kind of salaried government post, even if it might involve menial duties. In the 1820's many aristocrats moved into such bureaucratic positions as justices of the peace, tax collectors, even postmasters. The fact that they often served honorably and efficiently did not reconcile the sons of the bourgeoisie, many of whom emerged from university or law school to find no official posts left open to them. The resentment of this latter group contributed bourgeois antagonism toward the Bourbon dynasty. |

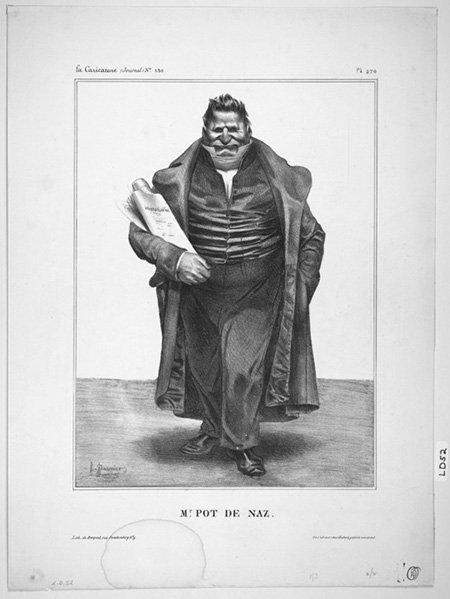

Honoré Daumier, Caricature of Joseph Baron de Podenas, 1833 |

Honoré Daumier, Caricature of a Bourgois Banker, 1835 |

From the outset the old aristocratic families were forced to share the top rung of society with those members of Napoleon's peerage that had rallied to the n cause in 1814. As one historian succinctly puts it, "Napoleon I was overthrown but his followers were not. They arranged the Bourbon restoration and were absorbed into the new system." Contempt for these upstarts was general among the "real" aristocrats, who nevertheless had to confine themselves to grumbling about it. Their bitterness was to be even greater toward the new peers named by "the usurper" Louis-Philippe after 1830. . . . After 1852 Napoleon III once again inflated the nobility by elevating his favorites to the peerage. The nineteenth century thus produced a far more complex aristocracy than that of the old regime -- one that by 1870 was divided into categories almost as distinct as geological strata. Until 1830 the aristocracy dominated politics, set the tone of society, and controlled much of the nation's wealth. From 1830 to about 1880, its monopoly was steadily eroded by the bourgeoisie. Under Louis-Philippe and successive regimes, it was the bourgeoisie that began to set the tone, no longer in obsequious imitation of the nobility but in conformity to its own developing set of standards and ideals, a curious blend of capitalist and precapitalist values. It was also the bourgeoisie that now provided the bulk of France's political elite, and that displaced the aristocrats at the top of the economic ladder [i.e. middle class]. One fact is clear: during the period from 1815 to 1870 (except for a brief interlude in 1848-49), it was only the upper echelons of the bourgeoisie that moved up into positions of political and social power. These were the wealthy bankers and business men: financiers like the Rothschilds and the Periers, industrialists like the Wendels and the Schneider brothers. For the most part, their rise to wealth and status was recent. . . . As long as the Bourbons reigned, the upper bourgeoisie was still overshadowed by the aristocracy; but its members did have the right to vote and to sit in parliament, where its spokesmen made up the liberal opposition. After 1830 it moved to the center of the stage, and stayed there (with a partial interruption in 1848) through the next four decades. But its hold on political and social power was not a total monopoly; those landed aristocrats who chose to collaborate with Louis-Philippe or with Napoleon III kept a share of influence, and both Legitimist and Orleanist peers kept much of their local power and social prestige. . . . |

| The petty bourgeoisie was an even more heterogenous category. It included the mass of little independents of city, town, and village-small enterprisers, shop keepers, artisans, clerks, schoolmasters, petty employees of the state. Some of them inherited an old family tradition of shopkeeping or craftsmanship; their fathers or grandfathers had been the sansculottes of the Great Revolution, the partisans of Robespierre and Marat. A far greater number had recently made the transition from what the eighteenth century had called le menu peuple or the "popular classes." Those who came of peasant origin usually took two or three generations to penetrate the lower levels of the bourgeoisie; the process of direct promotion from peasant to bourgeois was to remain uncommon until the later nineteenth century, when access to the bourgeoisie became a matter of educational level and achievement. . . |

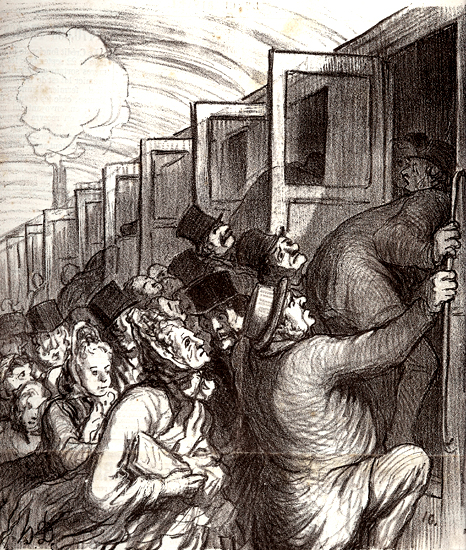

Honoré Daumier, The Pleasure Train (1843) |