The Revolution Becomes Radical

The revolution had three phases. The liberal phase found France under a constitutional monarchy during the National Assembly (1789–1791) and Legislative Assembly (1791–1792). After the destruction of absolutism and feudalism, legislation in this period guaranteed individual liberty, promoted secularism, and favored educated property owners. The aforementioned Declaration of Rights proclaimed freedom of thought, worship, and assembly as well as freedom from arbitrary arrest; it enshrined the principles of careers open to talent and equality before the law, and it hailed property as a sacred right (similarly, the National Assembly limited the vote to men with property). Other laws, enacted in conformity with reason, contributed to the “new regime.” They offered full rights to Protestants and Jews, thereby divorcing religion from citizenship; they abolished guilds and internal tolls and opened trades to all people, thereby creating the conditions for economic individualism; they rationalized France’s administration, creating departments in the place of provinces and giving them uniform and reformed institutions. Significantly, the National Assembly restructured the French Catholic Church, expropriating church lands, abolishing most monastic orders, and redrawing diocesan boundaries.

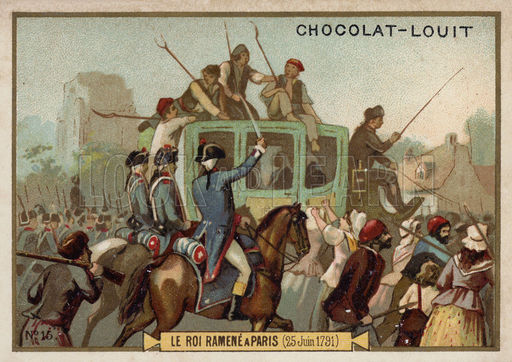

The revolution did not end despite the promulgation of the constitution of 1791. King Louis XVI had never reconciled himself to the revolution and as a devout Catholic was distressed after the pope condemned the restructuring of the church (known as the Civil Constitution of the Clergy). Ultimately, the king attempted to flee France on June 20, 1791, but was stopped at Varennes. Radicalism constituted another problem for the assembly, for Parisian artisans and shopkeepers (called sans-culottes ) resented their formal exclusion from politics in the Constitution and demanded legislation to deal with France’s economic crisis and the revolution’s enemies, particularly nobles and priests. After Varennes, radicals called increasingly for a republic. In addition, revolutionaries’ fears of foreign nations and counterrevolutionary émigrés led to a declaration of war against Austria in April 1792. France’s crusade against despotism began badly, and Louis XVI’s veto of wartime measures appeared treasonous. On August 10, 1792, a revolutionary crowd attacked the royal palace. This “second revolution” overthrew the monarchy and resulted in the convocation of a democratically elected National Convention, which declared France a republic on September 22, 1792, and subsequently tried and executed the king.

This 19th century advertisement for chocolate shows how strong the memory of the French Revolution remained in France a century after the events. This image represents the unsuccessful attempt of King Louis XVI in 1791 to escape France and join the military forces of other countries attempting to destroy the Revolution. He and his family were recognized at the border and forced to return to Paris. From this moment they were seen as dangerous enemies of the nation.

This 19th century advertisement for chocolate shows how strong the memory of the French Revolution remained in France a century after the events. This image represents the unsuccessful attempt of King Louis XVI in 1791 to escape France and join the military forces of other countries attempting to destroy the Revolution. He and his family were recognized at the border and forced to return to Paris. From this moment they were seen as dangerous enemies of the nation.

The revolution’s second, radical phase lasted from August 10, 1792, until the fall of Maximilien Robespierre (1758–1794) on July 27, 1794. The Convention’s new declaration of rights and constitution in 1793 captured the regime’s egalitarian social and political ideals and distinguished it from the liberal phase by proclaiming universal manhood suffrage [i.e.the right of all males to vote], the right to education and subsistence, and the “common good” as the goal of society. The constitution, however, was never implemented amid the emergency situation resulting from civil war in the west (the Vendée), widespread revolts against the Convention, economic chaos, and foreign war against Austrian, Prussia, Britain, Holland, and Spain. Faced with imminent collapse in the summer of 1793, by spring 1794 the government had “saved” the revolution and organized military victories on all fronts.

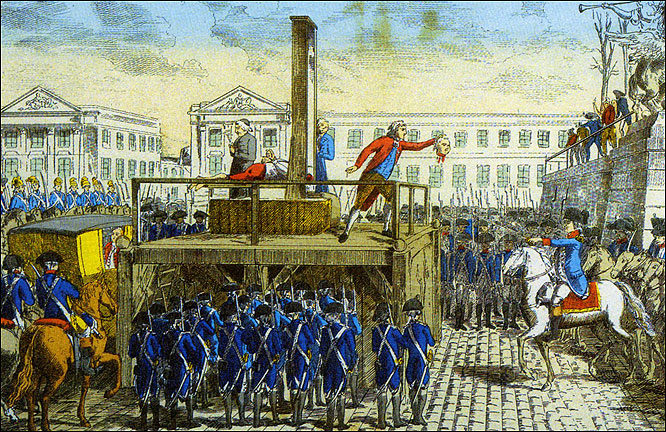

The stunning change of events stemmed from the revolutionaries’ three-pronged strategy under the leadership of Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety. First, they established a planned economy, including price controls and nationalized workshops, for a total war effort. The planned economy largely provided bread for the poor and matériel for the army. Second, the government forced unity and limited political opposition through a Reign of Terror. Under the Terror, the Revolutionary Tribunal tried “enemies of the nation,” some 40,000 of whom were executed—often by guillotine—or died in jail; another 300,000 people languished in prison under a vague “law of suspects.” The unleashing of terrorism to silence political opponents imposed order at the cost of freedom. It raised complex moral issues about means and ends and has led to vigorous historical debate: Was the Terror an understandable response to the emergency, one that saved the revolution from a return of the Old Regime, or was it a harbinger of totalitarianism that sacrificed individual life and liberty to an all-powerful state and the abstract goal of regenerating humankind? Finally, the revolutionary government harnessed the explosive force of nationalism. Unified by common institutions and a share of sovereign power, desirous of protecting the gains of revolution, and guided by a national mission to spread the gospel of freedom, patriotic French treated the revolutionary wars as a secular crusade. The combination of a planned economy, the Reign of Terror, and revolutionary nationalism allowed for a full-scale mobilization of resources that drove foreign armies from French soil at the Battle of Fleurus on June 26, 1794.

As part of its efforts to end the inequality that had traditionally marked French society, the Revolution confiscated most of the property that the Catholic church had accumulated over the centuries and demanded that priests sign an oath recognizing the legitimacy of the new political order. Many refused and worked with the internal external enemies of the Revolution to return France to the "ancient regime" (the system before the Revolution). The radical leaders of the Revolution imprisoned or executed many of them as traitors to the nation. The memory of this conflict continued to shape French society through the Second World War, and many Catholic conservatives continued to refuse to accept any government accept any government except a traditional monarchy.

As part of its efforts to end the inequality that had traditionally marked French society, the Revolution confiscated most of the property that the Catholic church had accumulated over the centuries and demanded that priests sign an oath recognizing the legitimacy of the new political order. Many refused and worked with the internal external enemies of the Revolution to return France to the "ancient regime" (the system before the Revolution). The radical leaders of the Revolution imprisoned or executed many of them as traitors to the nation. The memory of this conflict continued to shape French society through the Second World War, and many Catholic conservatives continued to refuse to accept any government accept any government except a traditional monarchy.

The Guillotining of Louis XVI, 1792

|

|

.