The July Monarchy

Colin Jones, Paris: Biography of a City, pp.270-274

| The collapse of the restoration of the Bourbon Monarchy in three days of rioting in Paris (the Trois Glorieuse as the French would remember them) led to the establishment of the relatively moderate July Monarchy described below. Although rioters seemed intent on expunging royal symbols in the city, the Trois Glorieuses produced neither a republic (the thought of which frightened the middle classes) nor a Bonapartist restoration. Political manoeuvring centred on the Hotel de Ville, where Lafayette, in a deliberate replay of 1789, was appointed commander of a reconstituted National Guard (it had been disbanded for political indocility in 1827). [Yes, that is the same Lafayette who as a young man served in the American Revolution.] The upshot was the continuation of monarchy, albeit with a new king. The throne of the socalled July Monarchy was offered to, and accepted by, the duc d'Orleans. The Orleans house had cultivated support in Paris since the time of Louis XIV. The new ruler, Louis-Philippe the First (and last), was eldest son of Philippe-Egalite, the Revolutionary duke who had turned his residence the Palais-Royal into a hotbed of radicalism, and voted for the death of Louis XVI. Louis-Philippe himself had served with some distinction in the republican army before fleeing the Terror in 1793, and since 1815 had been reinstalled in the Palais-Royal. The new king now abandoned his ancestral Palais-Royal to establish himself in the Tuileries (which still lacked, it must be said, some elementary comforts -- there was no running water until 1848). In the Trois Glorieuses [the three glorious days in which the Bourbon monarchy was overthrown in 1830]Paris had changed the government of France-and done so with little damage to itself: only 600 rioters and 150 soldiers died in the disturbances. |

| A |

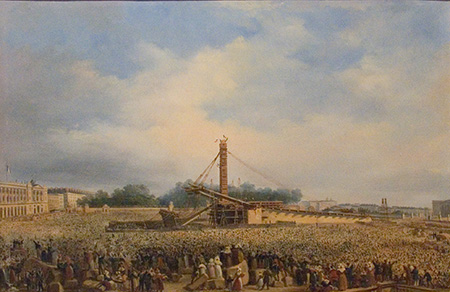

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (1830) The city which had served Louis-Philippe his crown on a platter received warm royal endorsement. The new king declared Paris to be 'his native city', named his first grandson the comte de Paris, confirmed the continuance of the National Guard, resided in the Tuileries and walked the city streets with an umbrella on his arm. 'What the people need now,' Lafayette had told him during power negotiations in 1830, 'is a popular king, surrounded by republican institutions.' Louis-Philippe consequently introduced a more liberal constitution, and nurtured a popular personal image. He distanced himself from the aura of the Restoration by rejecting anything which smacked of the old union of 'Throne and Altar'. The Rue Charles X was thus renamed the Rue Lafayette; the old Royal Household was disbanded; the king ostentatiously refused to attend mass in public each Sunday; and public religious processions in Paris were banned. Royal ceremonies became secular, populist occasions. In a commemoration of the Trois Glorieuses in 1840, for example, the king in augurated a column honouring the July combatants in the Place de la Bastille, where it still stands. Modest in its political claims, the new regime was modest in its attitudes towards public monuments within the capital. The July Monarchy was more of a finisher than an initiator in matters monumental. Most of its major achievements were inherited projects, many of which had ground to a halt at some stage since 1789. . . . Further completion and embellishment included the Arc de Triomphe de l'Etoile, and a remodelled Place de la Concorde ( both 1836). A wellattended spectacle saw the planting that year, on the site of Louis XV's old equestrian statue, of the Luxor column, dating from the thirteenth century BC -- making it the oldest object in Paris by more than a millennium. . . .

The most imposing of these gestures of continuity with Paris's past was the decision to bring back Napoleon's remains from Saint Helena. The publication in 1823 of Las Cases's memoirs of Napoleon on Saint Helena had helped to stimulate a more positive reassessment of the Empire. In these hard times Napoleon's reputation rose too among Parisian workers, for whom the emperor had always tried to provide work, bread and circuses. Following several years of negotiations with the British, the transfer was agreed in 1840. After a long journey by sea and land, the imperial remains made a long procession through the streets of Paris on the freezing day of 5 December 1840. The hearse, designed by the architect Henri Labrouste (whose work includes the cavernous Bibliotheque Nationale on the Rue de Richelieu ), was a highly decorated and monumental assemblage ten metres high and four wide. Its progress under the Arc de Triomphe and along the Champs-Elysees towards the Invalides, where the remains would rest henceforth, was watched by hundreds of thousands. 'It feels as though the whole of Paris has slipped into one half of the city,' noted Victor Hugo, 'like liquid in a tilted vase. '

King Louis Phillipe

|

|

|

T |

|

Honoré Daumier - Rue Transnonain, April 15, 1834

|

A provocative decision by Bourbon supporters to hold a commemorative mass in the church of Saint-Germain!'Auxerrois on the anniversary of the duc de Berry's assassination led to the church being sacked and burned by the anti-clerical descendants of the sans-culottes. “Sans-coulottes” was a term used earlier to describe the radicals from the poorer classes of Paris.] Although the cholera epidemic of l 832 quietened things down somewhat, 1833 and 1834 witnessed a long series of acts of collective militancy. In a horrible incident in 1834-the so-called 'massacre of the Rue Transnonain -- the forces of order killed rebels and bystanders in cold blood. If popular agitation died down from mid-decade, it had not gone for good, as was to be shown by the revolutionary journees [days]of February 1848 which deposed Louis-Philippe. |

The Tomb of Napoleon, Invalides