The Fall of the July Monarchy, Alistair Horne, Seven Ages of Paris

Like that of 1968, the year 1848 was one of revolt and revolution across the board. In Europe, old political structures collapsed like houses of cards. Given the paucity of communications , what was remarkable was how swiftly revolution spread across Europe. "There was," wrote a British historian, "a sound of breaking glass in every continental capital west of the Russian frontier." In Vienna even the seemingly immortal Metternich -- who had given Europe its past three decades of peace -- was deposed. . . .

In Europe, old political structures collapsed like houses of cards. Given the paucity of communications , what was remarkable was how swiftly revolution spread across Europe. "There was," wrote a British historian, "a sound of breaking glass in every continental capital west of the Russian frontier." In Vienna even the seemingly immortal Metternich -- who had given Europe its past three decades of peace -- was deposed. . . .

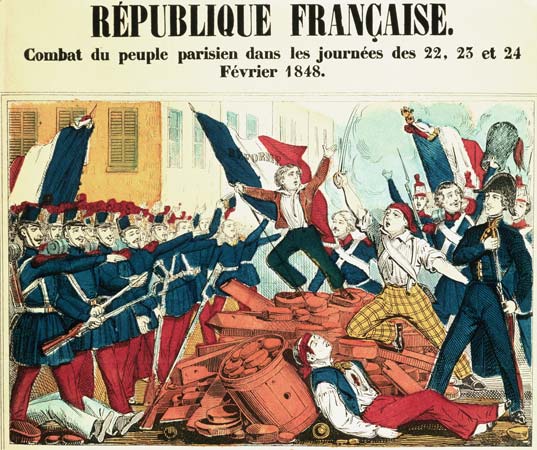

It had all begun in Paris, in the last week of February. Once again, as during the last years of the Napoleonic era, there had been a prelude of poor harvests in 1846-7. On 22 February, a mass banquet, planned by the Opposition to give expression to Parisian discontent over government resistance to reform, was abruptly canceled. The following afternoon fighting broke out at the Porte Saint-Martin and a number of people were killed. There were shouts of "Down with Guizot!" -- who, as successively Louis-Philippe's Minister for Foreign Affairs and Prime Minister, had been the virtual ruler of France for the past eight years. Stones were thrown at the Quai d'Orsay, railings ripped out at the Chamber of Deputies, and a highly reluctant Thiers seized and carried shoulder-high by demonstrators. Barricades began to appear on the Rue de Rivoli. Worst of all, there were cries of "Vive la Reforme!'' and "Down with Guizot!" from the ranks of the National Guard, formed of middle-class Praetorians.

In alarm, the King jettisoned Guizot, but it was already too late. Near the elegant Boulevard des Capucines, the progress of "a decidedly villainous-looking mob" singing revolutionary songs was blocked by the loyally Royalist 14th Battalion. When one of the rioters thrust his torch in the face of its commanding officer, a trigger-happy Corsican sergeant shot him dead. That single shot changed the course of French history: On hearing the shot, and thinking their chief threatened, the nervous soldiers fired a ragged volley into the crowd. Count Rodolphe Apponyi, an attaché at the Austrian Embassy, saw "a hundred or more people laid low, stretched out, or rolling over another, shrieking and groaning." News of the shooting raced through Paris. On his way back to his Embassy Apponyi observed an angry mob heading for the Tuileries [the royal palace at the time].

|

Cartoon by Honore Daumier of Street Urchins Playing in the Tuilleries (the Royal Palace) after the Flight of Louis-Phillipe. This image is playful, but the propertied classes in Paris were disturbed by the idea of the poor in Paris looting a palace because it represented a threat to property and to order. |

Hardly had Louis-Philippe left than the mob invaded the Tuileries, just as they had done in the last days of Louis XVI. Though some looters were shot on the spot, women and children dressed themselves up in valuable tapestries; sofas and armchairs were flung out of the windows, portraits of the King were ripped to pieces, even Voltaire's bust was hurled down into the courtyard. The throne was carried in triumph through Paris, and set on fire at the foot of the July Column (which commemorated the July Days of 1830), while a great crowd danced round it. The Palais Royal was also sacked and gutted. A republic was pro claimed, as workers flocked to the Hotel de Ville.

France, and Paris, was taken totally by surprise by the events of February 1848. With 350 dead over the three days, it was the least bloody uprising of the century. For many, the dominant bourgeoisie [the middle class] had become, as Tocqueville saw it, "a small aristocracy, corrupt and vulgar, by which it seemed shameful to let oneself be ruled." Few, probably, had really wanted Louis-Philippe to go. Says Tocqueville again, "this time a regime was not overthrown, it was simply allowed to fall." In truth, the monarchy had died out of sheer boredom, for "lack of panache," in a uniquely French fashion. The good King had given France some of the happiest years in her history, but, as has been remarked, "the French do not live on happiness."

As the July Monarchy crumbled, so romantisme petered out. In its place came freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, universal suffrage and the right of every Parisian to join the National Guard. In Saint Petersburg, recalling what had followed 1792, a thoroughly alarmed Tsar shouted, "Gentlemen, saddle your horses; France is a Republic!" In fact, the Second Republic was virtually doomed before it started. Once again the Parisian proletariat realized that -- although, much more than in 1789, this had been a rising of the slums and the workers' districts -- the new revolution had not been won by them. They emerged from it more abjectly poor, but more concentrated and more aware of their own strength than at any time before. These were conditions that remained highly favourable to revolt, and as early as June 1848 it broke out again in Paris -- this time to be suppressed with far greater violence.

Horace Vernet, Barricade on the rue Soufflot (1848)