The End of the Revolution

| The revolution’s third phase, the Thermidorian and Directory periods, commenced with the overthrow of Robespierre and the dismantling of the Terror on 9 Thermidor (July 27, 1794) [Thermidor was one of the months on the new revolutionary calendar] and lasted until the coup d’état on November 9, 1799, that brought Napoléon Bonaparte (1769–1821) to power. A new constitution in 1795 rendered France a liberal republic under a five-man executive called the Directory. The reappearance of property qualifications for political office sought to guarantee the supremacy of the middle classes in politics and to avoid the anarchy that stemmed from popular participation. The seesaw politics of the Directory, which steered a middle course between left-wing radicalism and right-wing royalism, witnessed the annulment of electoral victories by royalists in 1797 and by radicals (Jacobins) in 1798 and undermined faith in the new constitution. Similarly, the regime won enemies with its attacks on Catholic worship while failing to rally educated and propertied elites in support of its policies. Initially, continued military victories by French armies (including those by Napoléon in Italy) buttressed the regime. But the reversal of military fortunes in 1799 and ten years of revolutionary upheaval prompted plotters to revise the constitution in a more authoritarian direction. In Napoléon, the plotters found their man as well as nearly continual warfare until 1815. “Citizens,” he announced, “the Revolution is established on the principles with which it began. It is over.” The French Revolution is the quintessential revolution in modern history, its radicalism resting on a rejection of the French past and a vision of a new order based on universal rights and legal equality. The slogan “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, or Death” embodies revolutionaries’ vision for a new world and their commitment to die for the cause. . . . Students frequently puzzle over the significance of the revolution when, after all, the Bourbons were restored to the French throne after Napoléon’s final exile in 1815. But the restoration never undid the major gains of the revolution, which included the destruction of absolutism, manorialism, legal inequality, and clerical privilege, as well as commitments to representative government, a constitution, and careers open to talent. Once the revolutionary genie announced the principles of national sovereignty, natural rights, freedom, and equality, history has shown that it could not be put back in the bottle. |

Jacques-Louis David, Bonaparte Crossing the Alps (1801)

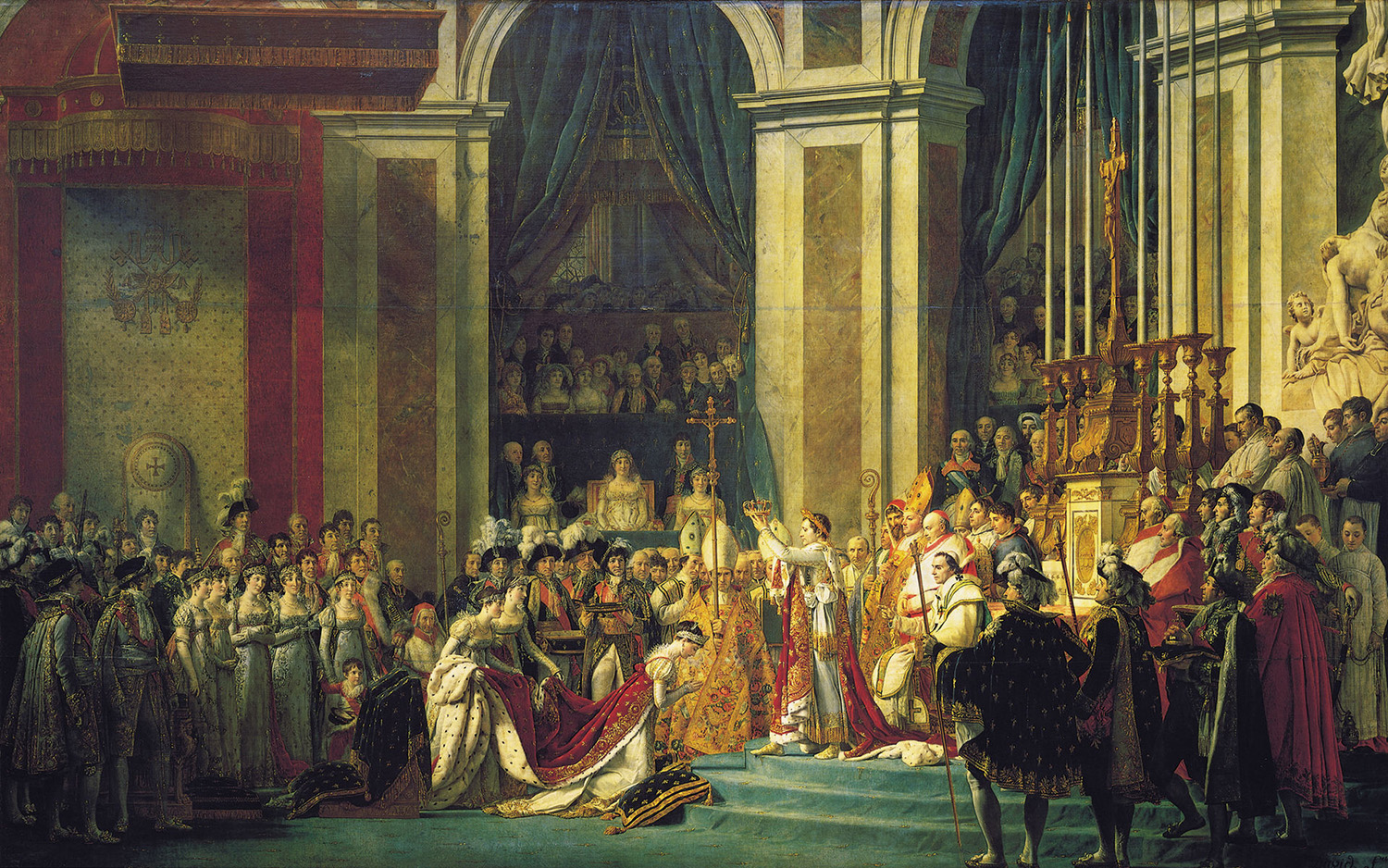

Jacques-Louis David, The Coronation of Napoleon (1805-1807)

|