Notre Dame and the Gothic Style

James H.S. McGregor, Paris from the Ground Up (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009), pp.42-44.

The style Suger [the abbott who had overseen the construction of the first church in Gothic style at Saint Denis on the outskirts of Paris] advocated, and the one that  Bishop Sully inaugurated in Paris, has, since the Renaissance, been called Gothic. Art historians have described the Gothic as an architecture of the sky rather than the earth. While it created enclosed spaces of unparalleled extent, its distinctive features are its steep arches, vertical towers, and soaring walls. Its heavenly aspirations are reflected in the beaked pinnacles that top every vertical and extend the building's reach as high as possible into the sky. The sky itself entered the structure through enormous windows. Filtered by richly colored glass that changed intensity as the day passed, light became the most absorbing and lively spectacle within these vast spaces.

Bishop Sully inaugurated in Paris, has, since the Renaissance, been called Gothic. Art historians have described the Gothic as an architecture of the sky rather than the earth. While it created enclosed spaces of unparalleled extent, its distinctive features are its steep arches, vertical towers, and soaring walls. Its heavenly aspirations are reflected in the beaked pinnacles that top every vertical and extend the building's reach as high as possible into the sky. The sky itself entered the structure through enormous windows. Filtered by richly colored glass that changed intensity as the day passed, light became the most absorbing and lively spectacle within these vast spaces.

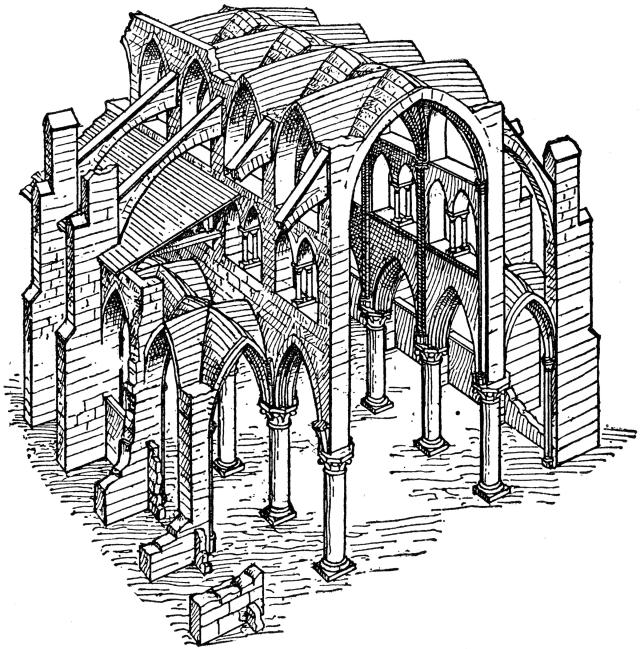

These characteristics are most apparent when Gothic cathedrals are compared to churches of the Romanesque period that came immediately before. Yet despite the obvious differences between the two, the new architecture, like its Romanesque predecessors, was firmly rooted in the early Christian basilica. The ground plan of Saint Stephen [an earlier church on the Île de la Cité that was torn down to make room for Notre Dame] was a scaleddown version of the ground plan of the Gothic church that supplanted it. And when viewed in section, the low side aisles and higher central nave of Saint Stephen were preserved in the cathedral of Notre Dame. Though fixed by tradition and by liturgical needs, these architectural forms also represented a response to the pragmatic demands of the building itself. A basilica was designed to provide as much open floor space as possible and to allow light to reach every part of the interior. Windows in the side wall lit the aisles, but the central nave was too far from the side walls to receive much light from windows there. Skylights would have been an ideal solution, but they were a technological impossibility before the nineteenth century. The next best thing was to build the walls of the central section higher than the roofs that covered the aisles and to put windows in those walls. Gothic churches are higher than most early Christian churches, but they are lit in the same way.

The walls of early Christian basilicas were made from nearly uniform masses of brick or stone. Their strength depended on their thickness, and cutting holes into them made them weaker. Because of the need to maximize visibility at floor level, the high central walls of early Christian basilicas rested on colonnades (rows of evenly spaced columns) or arcades (rows of evenly spaced arches supported by columns or piers). The openings between the columns or piers made it possible for people in the side aisles to see what was going on around the altar of the church. But slender supports meant that nave walls could not be very heavy or thick, and this limitation restricted their height. And because of the walls' uniform construction, the windows cut into them could not be very large. Yet glazing even small windows was a difficult problem throughout the late antique and early medieval period. Glass was extremely expensive and hard to come by, and windows in many early Christian basilicas were left unglazed.

The walls of early Christian basilicas were made from nearly uniform masses of brick or stone. Their strength depended on their thickness, and cutting holes into them made them weaker. Because of the need to maximize visibility at floor level, the high central walls of early Christian basilicas rested on colonnades (rows of evenly spaced columns) or arcades (rows of evenly spaced arches supported by columns or piers). The openings between the columns or piers made it possible for people in the side aisles to see what was going on around the altar of the church. But slender supports meant that nave walls could not be very heavy or thick, and this limitation restricted their height. And because of the walls' uniform construction, the windows cut into them could not be very large. Yet glazing even small windows was a difficult problem throughout the late antique and early medieval period. Glass was extremely expensive and hard to come by, and windows in many early Christian basilicas were left unglazed.

A new approach to building nave walls was the first of two striking innovations that transformed the lighting of church interiors in the Gothic era. No longer envisaging the walls of a building as a continuous protective and supporting structure like the exoskeleton of a beetle, Gothic designers imagined walls as a system of supports and protective membranes. Instead of using short columns to support a heavy wall, tall columns were extended from floor to ceiling, where their tops were joined with ribs to create vaults and roofs. These massive columns, which could take many forms, bore the weight of the structure. The stonework between columns provided cross-bracing and kept out the elements (much like plywood sheathing nailed to studs in a modern house wall), but it bore little weight. Even when the wall was pierced through with enormous openings for windows, the building remained strong.

The creation of Gothic architecture coincided with a revolution in the production of glass. For reasons that remain unclear, techniques that Byzantine artisans had understood for centuries suddenly came into widespread use. The glass they made was of a particular type, not for the most part clear but richly colored in a limited range of very strong but still harmonious shades. Sometime in the late tenth or early eleventh century, builders began to glaze the small slit-like windows of Romanesque churches with mosaic patterns made from this colored glass. By the twelfth century in Paris and the surrounding towns in the lie de France, glassmakers were joining the construction crews of the great cathedrals and creating masterpieces of stained glass.

Notre Dame -- Nave