Signs, Streets, and the Chat Qui Peche (Fishing Cat Street)

Sonia, Alison, and Rebecca Landes, Paris Walks (New York: Henry Holt, 2005), pp.44-45, 54-56.

Medieval Advertising

The first commercial standards were put up by taverns and hotels so that a foreigner could find a place to eat and sleep in a strange city. These standards often  represented a bundle of straw, which gives a good idea of the character of the sleeping accommodation. Even today there is hardly a city in France without a hotel called the Lion d'Or (golden lion) or, in rebus form, le lit [ou] on dort (the bed [where) one sleeps).

represented a bundle of straw, which gives a good idea of the character of the sleeping accommodation. Even today there is hardly a city in France without a hotel called the Lion d'Or (golden lion) or, in rebus form, le lit [ou] on dort (the bed [where) one sleeps).

In the thirteenth century, the commercial standard was soon understood to be a smart way to advertise; by the fifteenth, it had become a serious problem. The standards were made from sheets of iron, cut and painted and hung on long poles to extend into the street past the large shop shutters. Like signs today, they were hung out as far as possible and made as large as possible to attract the most attention.

A parfumerie (perfume shop) had a standard of a glove, each finger of which could have held a three-year-old child. A dentist hung a molar that was the size of an armchair. These standards were constantly threatening to fall; one man was reputedly killed when the dentist's tooth fell on his head.

The combination of the shutters, an open sewer running down the center of the unpaved street, and huge groaning and clanking signs blocking out the sun made the streets dark and cluttered.

For reasons of safety rather than aesthetics, the government tried to pass legislation to limit the size of signs. In 1667 they said the signs could be no more than thirty-two inches wide and had to be hung at least fifteen feet above the ground, so that horsemen might ride safely in the streets. It was not until 1761 that standards were banned altogether, to be replaced by the old-style wall decoration like the Cygne de la Croix. Visit the Hôtel Carnavalet , the Museum of the History of Paris, in the Marais for an exhibit of standards .

Since literacy was rare, the names were more often simply visual recognition or mnemonic devices. Some were mystifying: The Bottle Tennis Court, The Small Hole, and The Cage. Other names were clearer. The Tree of Life was a surgeon's house; The Red Shop, a butcher shop (the surgeon might have used that one too); The Reaper, a bakery (another possibility for the surgeon). One common name whose symbolism was clear in the Middle Ages was the Salamander. Salamanders were at that time believed to be impervious to fire, and therefore salamander was the old name for asbestos, the "wood that wouldn't bum." Bakers often took this name to symbolize their clay baking ovens, and the word is still in use today for the ceramic room heaters commonly found in Europe.

Many of the names were religious, some specifically so: The Golden Cross, The White Cross, The Red Cross, The Name of Jesus, The Fat Mother of God (which was not vulgar but , rather, complimentary in the hungry Middle Ages). Some names were only vaguely religious in that they used the number three and thus invoked the Trinity. The number three was extremely popular: The Three Catfish, The Three Goddesses, The Three Pruning Knives , The Three Torches, The Three Panes (this was a bakery and not a glazier's), The Three Nuns' Coifs, The Three Doves, The Three Fish, The Three Pigeons.

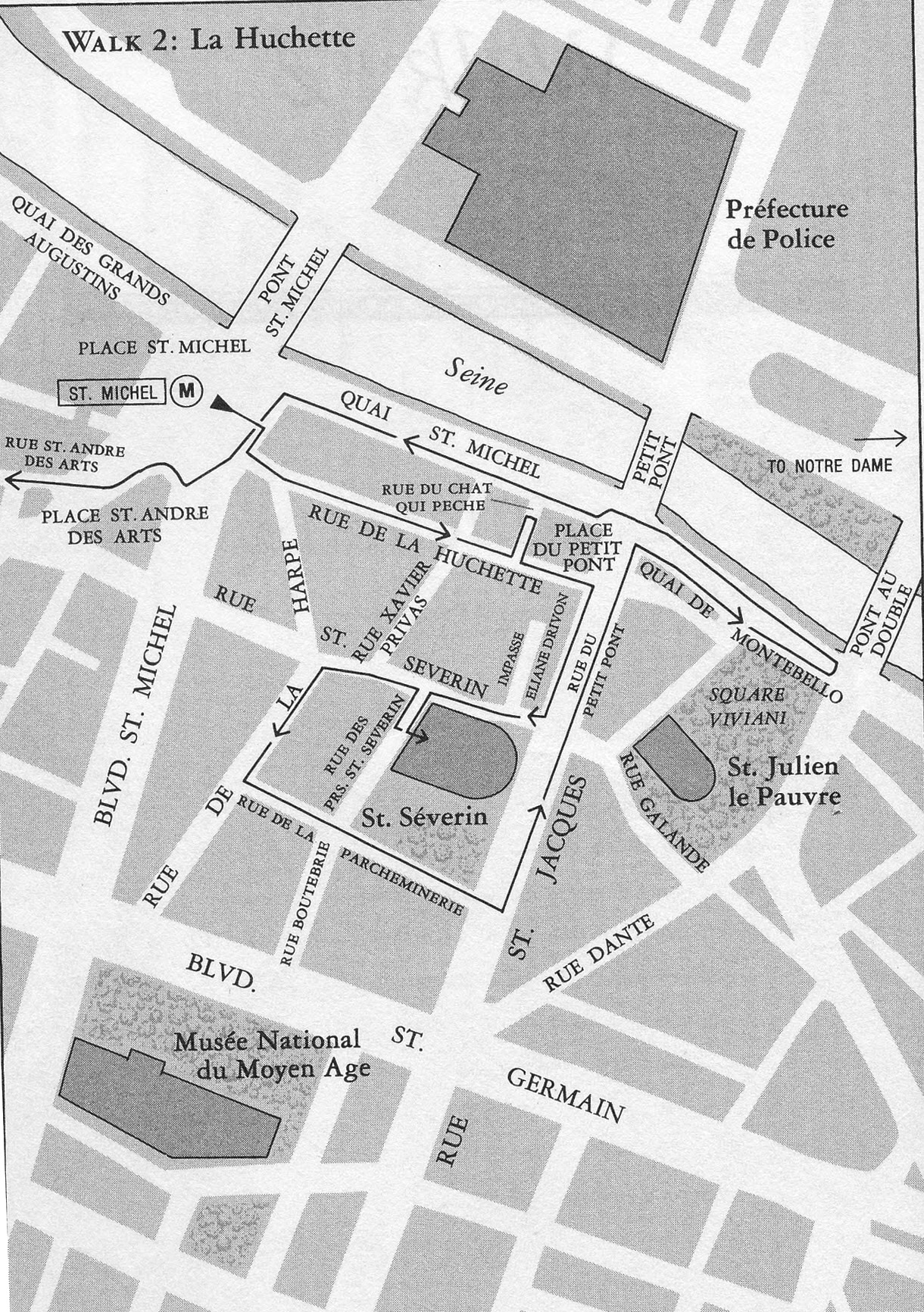

R u e d u C h a t q u i P e c h e ((Fishing Cat Street) [See map at the bottom of the page]

Look down the alley to the left at one of the most nondescript but oft-described streets in Paris, the rue du Chat qui Peche (street of the fishing cat). It took its name from a sign that hung above a shop, no doubt a fish shop, though no source actually says it was. Before the street took its present name, it was called the rue des Etuves (street of steam baths). There were half a dozen such streets and alleys in the Paris of the late thirteenth century, and some twenty-six bathing establishments. Every morning the crier was out on the street calling to prospective clients: "Li bains sont chaut, c'est sanz mentir!" (The baths are hot-no fooling!) They were hot in more ways than one. Many of them provided mixed bathing and supplementary services. One preacher warned his flock, "Ladies, do not go to the baths, and don't do you-know-what there." The combination of clerical disfavor and public harassment reduced the number of these establishments to two by the early seventeenth century. The result was a malodorous population. Those who could afford to doused themselves with perfume; the others -- well, people's noses must have been tougher then.

from a sign that hung above a shop, no doubt a fish shop, though no source actually says it was. Before the street took its present name, it was called the rue des Etuves (street of steam baths). There were half a dozen such streets and alleys in the Paris of the late thirteenth century, and some twenty-six bathing establishments. Every morning the crier was out on the street calling to prospective clients: "Li bains sont chaut, c'est sanz mentir!" (The baths are hot-no fooling!) They were hot in more ways than one. Many of them provided mixed bathing and supplementary services. One preacher warned his flock, "Ladies, do not go to the baths, and don't do you-know-what there." The combination of clerical disfavor and public harassment reduced the number of these establishments to two by the early seventeenth century. The result was a malodorous population. Those who could afford to doused themselves with perfume; the others -- well, people's noses must have been tougher then.

This narrowest street in Paris was, contrary to what you might expect, wider in the sixteenth century. The six-foot-wide alley, with its gutter of water (and urine) running down its middle, looks and sometimes smells like a medieval street. Walk up the alley, away from Huchette . The alley suddenly widens, brightens, and then opens onto the Seine and, to the right, a surprise view of Notre-Dame. In the sixteenth century this street, like Xavier Privas, tumbled down into the Seine. It too was gated in at night, though no sign of the gate can be seen in the stone.