SUGER AND THE TWELFTH-CENTURY RENAISSANCE

Alistair Horne, Seven Ages of Paris (New York: Vintage, 2004),pp.7-8.

The three decades spanned by Louis VI's reign (1108-37) represent an important turning point, not just in the artistic development of Paris, but in the cultural history

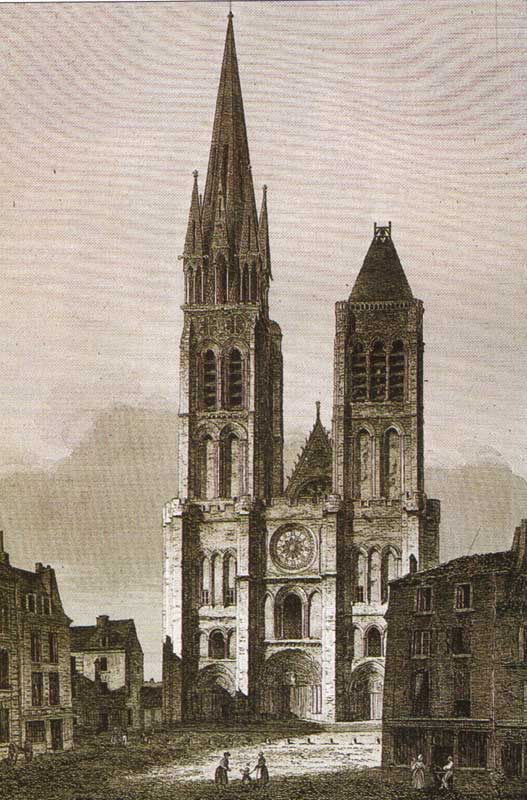

West façade of Saint Denis, before the dismantling of the north tower (c. 1844 – 1845) |

of the West as a whole. Until one considers the dates, it is hard to grasp that what is known -- with considerable justification -- as the twelfth-century Renaissance, a true window of bright light in the Middle Ages, took place over a century before Giotto and Dante were even thought of, its landmarks and symbols the soaring gothic glories of numerous cathedrals . Originating supposedly in the East, it was in France (and especially in the nuclear Ile de France [the area around Paris]) that the innovation of gothic religious architecture found its most fertile ground and its inspiration. Close to the heart of it was a most remarkable Parisian-Abbe Suger.

Abbot of Saint-Denis [a monastery north of Paris] for thirty years until his death in1151, Suger was the first in a long line of able and enlightened ministers to the kings of France -- a diplomat, a statesman and a businessman, outstanding for his architectural good taste, as well as being a churchman who built (or rather rebuilt) the magnificent basilica of Saint-Denis. . . .

In marked contrast to his sovereign, the Abbot of Saint-Denis was a monk of modest stature, thin, sickly and in poor health, yet with immense energy, he was to prove of considerably greater historical importance than either of two kings he so faithfully served. Suger was both product and epitome of the twelfth-century Renaissance, as well as being a profound influence in the aesthetic development of France and of Paris. In that all-too-brief passage of enlightenment between the Dark Ages and the purging of heresy in the later Middle

Ages, the best and brightest arbiters of Church thought had little difficulty in squaring love of God with love of worldly beauty and of the sensuous world.

Suger himself could be quite unashamed in his passion for exotic stained glass, and for the hoard of gold, jewellery and other objets d'art which he crammed into the treasury at his beloved Saint-Denis, but he was confident that there was a pragmatic excuse for church embellishment: if the common people (that is, the illiterate) could not grasp the Scriptures, then they could best be taught them through the medium of pictures, or stories carved in stone. . . .

"In the Middle Ages," wrote Victor Hugo, "human genius had no important thought which it did not write down in stone." In1132, so it is recorded, the gothic style with its soaring spires, lofty rib vaults and pointed arches took root in France when Suger decided he had to rebuild, on a vastly expanded scale, the ancient romanesque abbey at Saint-Denis. Several times during his stewardship there had been distressing scenes on feast days, when the dense crowds had led to the faithful being trampled to death in the crush. There were even occasions when monks showing off the reliquaries had been forced to escape through windows to save them. Suger's great new basilica was consecrated no more than a dozen years after it had been conceived -- an xtraordinary achievement. No expense was spared in the richness of its decoration. It must surely be seen as a true testimony to the spirit of the age that, with such crude tools, simple measuring devices and rudimentary mathematics handed down from Euclid and Pythagoras, the architects and masons of Suger could create these lasting miracles of construction . "Who was the sublime madman," was the rhetorical question of Vauban, Louis XIV's great military architect, "who dared launch such a monument into the air?" as he contemplated the massive central tower of Coutances Cathedral (1220-50) that seems to float in the sky. Soon after the consecration of Saint-Denis, Suger's architect transported his know-how to Chartres, where, though it would be many years in completion, the finest of all the jewels of Latin Christendom was constructed. The great cathedrals of Sens, Lao Bourges, Rheims and England's Canterbury all owed something to the delicate little Abbot of Saint-Denis.

The Cathedral at Saint-Denis