The Place des Vosges -- Central Planning

Joan DeJean, How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City (New York: Bloomsbury,2014), pp.46-49.

In October 1604, when the Pont Neuf was opened to the public, the initial phase in Henri IV's master plan for the transformation of Paris was essentially complete. In fact, during the final months of 1603, the king had begun laying the groundwork for another project. He desperately needed to jump-start the Parisian economy, badly weakened by decades of religious warfare. Luxurious (and astronomically expensive) silk was then a darling of European fashion. France was importing great quantities from the dominant European producer, Italy, and the costly foreign import was draining French coffers. Henri IV thus decided to launch a silk industry in the French capital. What began as an attempt to revitalize Paris' economy subsequently evolved in ways no one could have predicted: the project resulted in the creation of both a ground breaking model for the city square and a major new neighborhood. In August 1603, when Henri IV assembled leaders of the business community to discuss the idea of opening a manufactory dedicated to the production of the highest quality silk upholstery fabric, there was little precedent for establishing any type of industry in an urban setting. In 1590, Pope Sixtus V had considered using the Colosseum for a manufactory to revive Italian wool production, but the plan was never carried out. To realize his design, Henri IV turned to six of the wealthiest tradesmen and city officials. This is the earliest example of a phenomenon characteristic of Paris' reinvention: grandiose royal visions largely financed by private investment. |

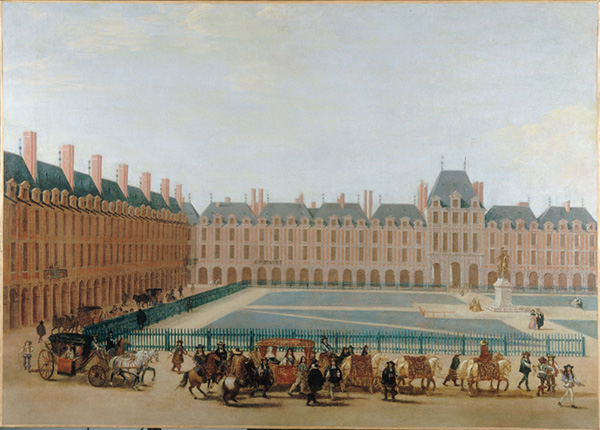

Place Royal c. 1660 |

The king offered those backers titles of nobility and tax-free business conditions for the silk manufactory. In January 1604, he provided land for the construction of workshops and housing for workers. In return, he asked only that they promise to keep the new silk manufactory operational until 1615. . . .

The king decided to use the existing commercial buildings as one side of the square. The three remaining sides were to be composed of what he called "pavilions,'' nine to a side. Their ground floor was designated as commercial space (shops selling the new manufactory's wares) with a covered arcade that would protect visitors from the elements. Their upper floors were to provide residences. The land was given to investors in the silk works and other loyalists to the crown for a symbolic annual rental fee.

They were free to plan the interiors of their pavilions, but their facades had to be identical --"built according to our design." Thus the pavilions became a spectacular founding example of terraced housing, houses of uniform height and with uniform fronts that share a wall with neighboring units. . . . The Place's pavilions had identical sloping slate roofs; their facades were composed of a mix of red brick and golden stone. The combination was not new to French architecture -- it had already been used in a few sixteenth-century chateaux -- but it was new in Paris, where it added a distinctly colorful footprint. The original owners also had to agree to "the same symmetry"-the same number of stories, of identical dimensions, the same kind of chimney in the same spot, the same number of windows and of uniform size. (There are in fact some variations, but they are small enough so that the impression of absolute harmony remains.)

Henri IV was so eager to see his latest project realized that he ordered it to be completed in a mere eighteen months. And to make sure that the workers kept hard at their task, he personally visited the construction site on a daily basis.

But despite the king's hands-on involvement, the Parisian silk industry was anything but a grand success. In April 1607, the king therefore abandoned his original goal and approved a significant modification: the workshops with which the entire project had begun were torn down and replaced with nine additional pavilions. Henri IV rewarded those who had gone about building most expeditiously.

The Place des Vosges [Formerly Place Royal] Today