A New Kind of Urban Space on the Île Saint-Louis

Joan DeJean, How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City (New York: Bloomsbury,2014), pp.66-68, 71-72, 76.

Once he had an island, [Christophe] Marie turned his attention to its

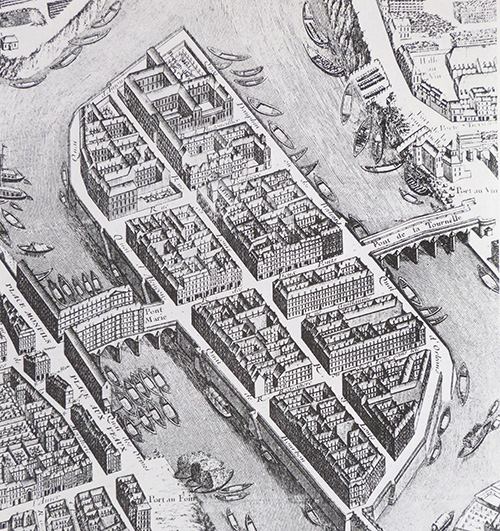

Map of Île Saint-Louis, 1739 |

infrastructure. At the center of a still medieval urban layout he introduced a tiny but perfect example of grid planning. This 1728 map of the island's definitive design shows how, in contrast to the largely random cityscape that surrounded it on all sides, the Ile Notre-Dame's streets intersected each other at right angles. Marie also gave Paris a preview of the wider thoroughfares soon to become common elsewhere in the city: the rue des Deux Ponts (originally the rue Marie) and the rue Saint-Louis (first called the Grande Rue) were a handsome four toises or about twenty-five feet wide. (Prior to the seventeenth century, Paris had almost no streets more than fifteen feet wide.) In his land mark 1684 Paris guidebook Brice, still in wonder at the island's streets, said that they "seemed to have been traced with geometrical instruments, in absolutely precise lines right up to the river's banks."

After streets came amenities. In the original 1614 contract, Marie had promised to construct those he considered most essential: a public fountain, a bath house, and an athletic facility, a jeu de paume or court for a precursor to modern handball. In new documents drawn up in 1623, he also included shops for the merchants he hoped to attract at the start-a butcher, a fishmonger, a rotisseur from whom residents could buy grilled meats, as well as bateaux à lessive, laundry boats that docked along the embankments so that residents could drop off their clothes to be washed. . . .

The island's architectural profile was also harmonious, since much of it was the product of one man's genius. Louis Le Vau, then at the beginning of one of the most brilliant careers in the history of French architecture, would design almost all the island's finest residences. . . . Le Vau developed on the island an architecture well ahead of its time, an interior architecture so innovative that its effects would be felt for centuries to come. He invented radically new layouts. He introduced rooms with novel shapes -- oval rooms in particular. He replaced the multifunctional, generic rooms that dominated earlier homes with previously unheard-of spaces, each dedicated to one particular activity, including the earliest dining rooms and bathrooms in Paris – and perhaps in Europe. Elsewhere in Paris it was only decades later that architecture began to catch up with what was already happening on the new island in the 1640s.

The fact that most of the residences on the island's periphery were designed over a short period of time and by the same architect created a stylistically unified ensemble. That sense of harmony begins with the impression of whiteness highlighted by the artist who first depicted the island. It was on the Ile Notre-Dame that the transformation of Paris from a capital in wood to a capital in stone and mortar truly began. . .

Today, countless tourist guidebooks and websites repeat that Paris is the most beautiful city in the world, in large part because of the structured handsomeness and uniformity of its residential buildings. Credit for the city's architectural distinction is always given to Baron Haussmann The Prefect of Paris under Napoleon III in the 1850s who opened up many of the grand boulevards of Paris]. And yet, two hundred and fifty years before Haussmann decreed the demolition of the grandest of its mansions, an artificial island in the Seine had convinced the greatest architects and architectural authorities of the day -- from Bernini to Eveyln -- that it held the key to the future of Parisian architecture and of notable urban architecture in general. Residential architecture uniform in design and gleaming in what was already seen as Paris' characteristic white stone, buildings laid out on generous parcels of land and facing wider and straighter streets -- before the end of the seventeenth century, ideas first realized on the Ile NotreDame [later named Île Saint-Louis] in the 1640s would spread widely through Paris.

By 1645, three visionary urban works -- the Pont Neuf, the Place Royale [now Place des Vosges], and the Île Notre-Dame -- had become the foundation for Paris' new image, as a city remarkable not only for its size but for its exciting and innovative constructions.

Île Saint-Louis Today