The Creation of the Île Saint-Louis

Joan DeJean, How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City (New York: Bloomsbury,2014), pp.62-64.

IN T H E 1630s , the Marais [the area on the Right bank near the Place Royal (Place des Vosges)] introduced Parisians to a novel urban experience -- life in an upscale enclave, a privileged space that afforded residents both easy access to the city's amenities and the sense of living in their own private haven. The lesson was not lost on the wealthiest Parisians of the day.

Soon after, another major new neighborhood was added in the heart of the city, so quickly that some said it seemed to have happened overnight. When it was done, one commentator quipped that it had taken less time to create the loveliest area in Paris than it had to destroy major parts of the city during the Wars of Religion.

The planners of the second neighborhood that developed in the 1630s took advantage of lessons learned from both the Pont Neuf and the Place Royale. They chose a site in the middle of the Seine, thus giving residents highly desirable access to the river views and the urban panorama that the New Bridge had first made essential to the Parisian experience. By building on virgin territory, they were able to showcase residential architecture on a scale not possible in an area with preexisting construction such as the Marais. This second neighborhood thus provided a rare occasion to try out innovative ideas in urban planning and residential architecture. And the experiment paid off: the area, a complete neighborhood planned and built from scratch, played a key role in the transformation of Paris into the most beautiful city in the world.

It all began with a marvel of technology that surpassed even the Pont Neuf 's construction.

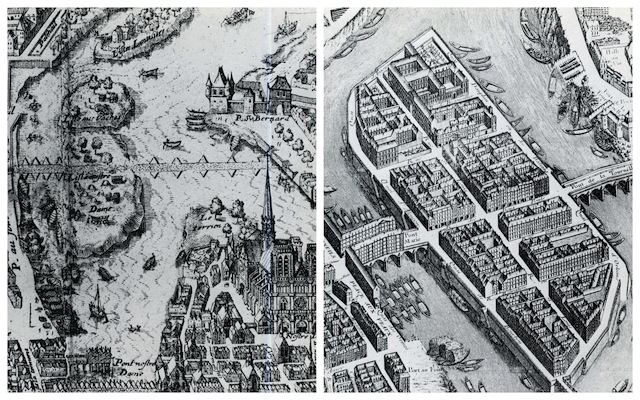

The Islands in the Seine Before and After the Creation of the Île Saint-Louis |

Henri IV initiated an undertaking without precedent and one not attempted again for nearly three centuries, the construction of a largely man-made island in a major urban river. Today, Parisians and visitors know the king's new island and the neighborhood developed on it as the "Ile Saint Louis."

The Ile Saint-Louis that visitors see today is a rare, almost perfectly preserved parcel of the urban past, an enclave that -- -nearly four centuries after its creation -- remains so close to its original incarnation that it could almost have spent those centuries in a time capsule. Its streets are still laid out as they were at the start; most of the residences are original, and they retain their original appearance.

Today, two islands are central to the romance of Paris' river: the Île de la Cite, with the spires of Notre-Dame and the Sainte-Chapelle, and the Île Saint-Louis. But from Roman times to the early seventeenth century, today's Île Saint-Louis was not one landmark island but two among a number of unprepossessing and uninhabited islets in the Seine. The larger of the two islets, Île Notre-Dame, owed its name to the fact that it was under the cathedral's jurisdiction. The name of the other -- Île aux Vaches, or Cow Island -- was more evocative of the modest role the two specks had played in the life of the city until then. Small flocks of sheep sometimes grazed there; hay was stocked on them; they found occasional use as a dueling ground or for small-scale boat building. This 1609 map of Paris depicts the two islets as absolutely devoid of construction.

The islets were also isolated, with no connection between them or to the mainland. Thus no large-scale activity could have taken place on them; sheep to be grazed , for example, had to be ferried over by boat. Then along came Christophe Marie, engineer extraordinaire and among the developers who found his calling as a result of the Bourbon monarchs' expansive vision for Paris. . .

In late 1609, Marie proposed yet another bridge, also for free, and this time in the material of the future: stone. The Place Royale was then still under construction; the bridge that Marie proposed was intended both to help connect the new square to the other bank of the Seine and to facilitate the flow of traffic through the city at large. His second bridge still stands and still bears the name of its developer: the Pont Marie.

This bridge became the springboard for one of Henri IV's most ambitious projects for Paris. The king bought those two undeveloped islets and gave them to Marie, to whom he assigned a far more ambitious under taking. He was to create an unprecedented kind of island, a modern island that would be a model of urban planning and add a highly desirable neighborhood to the city's historic center.