Politics, Culture, and Commerce on the Pont Neuf

Joan DeJean, How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City (New York: Bloomsbury,2014), pp.34-37.

And no one could have predicted how many activities would soon be vying for space on the bridge.

To begin with, the Pont Neuf provided one of the original illustrations of the big  city's ever-accelerating appetite for news and of the rapidity with which technologies were invented to satisfy that craving. Rumors quickly spread through the crowd, giving rise to an expression: c'est connu comme le Pont Neuf -- "everybody knows that already." For the most part, however, news spread in far more organized ways. . . .

city's ever-accelerating appetite for news and of the rapidity with which technologies were invented to satisfy that craving. Rumors quickly spread through the crowd, giving rise to an expression: c'est connu comme le Pont Neuf -- "everybody knows that already." For the most part, however, news spread in far more organized ways. . . .

Engraved images of crucial people and events in the news were posted on the bridge. They were also available for sale in the shops that many printers set up either on or near the bridge. The same technique was used for printed news. Placards and posters of varying sizes were displayed prominently on walls throughout Paris, but nowhere more so than on the Pont Neuf. Contemporary accounts describe people reading aloud the posted news for those unable to read. (It's very hard to determine exact literacy rates since many essential archives no longer survive, but we do know that literacy was significantly higher in Paris than in rural France. Evidence such as the posting of news on the Pont Neuf indicates that urban literacy was growing and that new techniques were being developed to take advantage of its spread and to encourage it.)

The existence of this informal newsroom on the bridge explains the way in which political sedition erupted in 1648, when violence returned to the streets of Paris for the first time since the 1590s. . . .

From then on, the Pont Neuf was considered a breeding ground for civil disorder. Edicts were repeatedly issued, forbidding "people of every rank from assembling on the Pont Neuf" -- but to no avail. Contemporary sources claimed that a post on the Pont Neuf one afternoon was sure to assemble a crowd overnight. In addition, political songs were so successfully deployed during the civil war that, by the time the war was over, a music industry had developed, with "Pont Neuf singers" specializing in songs referred to as "Pont Neuf songs," "Pont Neuf vaudevilles,'' "chronicles from the Pont Neuf," and eventually just simply as "Pont Neufs." Paris' most prolific seventeenth-century letter writer, the Marquise de Sevigne, said of such songs: "The Pont Neuf wrote them." One of the bridge's most ardent admirers, Jean-Baptiste Dupuy Demportes-he announced in 1750 his plan to publish six volumes devoted to its history- claimed that every great moment in French history had been com memorated in a song written and performed there.

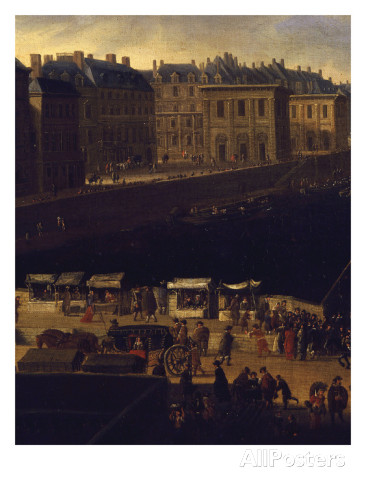

Those songs were just the tip of the iceberg. Until the first professional theaters opened their doors in the 163os, the Pont Neuf was the center of the Pa risian theatrical scene. Actors performed on makeshift stages such as the one depicted in this painting from the 166os. People from every walk of life have gathered on all sides-even under the stage. Some spectators have just wandered by, but a group of aristocrats has come expressly to catch the act. They have had their carriage turned around and backed up; a lady leans on the door. They thus have front-row seats.

Contemporary accounts make it clear that many acts seen on the bridge resembled today's stand-up comedy. Some performers became so famous that collections of their work circulated widely, both in the form of cheap pamphlets intended for a popular audience and of relatively pricey volumes for wealthier readers. . . .

Open-air performances contributed to the traffic gridlock, though not nearly so much as another kind of urban spectacle that also drew crowds to the bridge: shopping. As soon as the New Bridge was completed, a street market began. You could find trinkets, fashion accessories, and the most fetching bouquets in the city, sold by the bouquetieres, or "bouquet ladies of the Pont Neuf." Each merchant had a bare minimum of display space --a table, a trunk, a tent suspended over wares laid out on the ground. Most used portable stalls, pitched up on the central section and the sidewalks. Booksellers were the first to set up shop; there were soon at least fifty bookshops on the bridge. In 1619, still more began to open along the nearby quais. The little stands they folded up every evening and attached to the bridge's side parapet were the ancestors of the bookstalls on the banks of the Seine today. Because of the wide range of titles they displayed, contemporaries observed that the bridge gave Parisians access to the largest public library in the world.

Wealthy consumers being jostled about and distracted by everything from buskers to stray sheep must have seemed easy prey. Money was surely stolen and expensive small items such as pocket watches pinched in the midst of those crowds. These obvious kinds of robbery barely get a mention in the seventeenthcentury press, however. Instead, the New Bridge quickly acquired a reputation for a quite specific type of crime, clothing theft, and that of one item in particular: men's cloaks.

Procession of the King Accompanied by His Guards Crossing the Pont Neuf en Route to the Palace, Jan van Huchtenburg after Adam Frans van der Meulen, ca. 1670