Traffic on the Pont Neuf

Joan DeJean, How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City (New York: Bloomsbury,2014), pp.30-34.

One feature certainly guaranteed that visitors would leave with a "magnificent idea" of the city  of Paris: those sidewalks. The sidewalks on the Pont Neuf were the first the modern world had seen; they introduced Europeans to the idea of separating foot and vehicular traffic. Authors of guidebooks, aware that their readers would have had no previous experience with the phenomenon, explained, as Claude de Varennes did in 1639, that they were "absolutely reserved for pedestrians." Nemeitz's 1719 introduction to Paris still refers to the idea as a "new convenience" and one unfamiliar to foreigners. (It was only in 1781 that the first sidewalks in an actual Parisian street were added on the rue de l'Odeon, following the example of London's 1762 Westminster Paving Act.)

of Paris: those sidewalks. The sidewalks on the Pont Neuf were the first the modern world had seen; they introduced Europeans to the idea of separating foot and vehicular traffic. Authors of guidebooks, aware that their readers would have had no previous experience with the phenomenon, explained, as Claude de Varennes did in 1639, that they were "absolutely reserved for pedestrians." Nemeitz's 1719 introduction to Paris still refers to the idea as a "new convenience" and one unfamiliar to foreigners. (It was only in 1781 that the first sidewalks in an actual Parisian street were added on the rue de l'Odeon, following the example of London's 1762 Westminster Paving Act.)

For decades, no one could agree on what this convenience should be called. Banquette, used to refer to a protective ledge in fortifications from which soldiers could fire, was the preferred term, but some said levées, embankments or levees, while still others preferred allées, walkways. The word used today, trottoir, originated only in 1704.

And no one knew what to call those who used these banquettes. In official municipal documents, the people who walked there were called gens de pied, literally "people on foot," a military term for foot soldiers. By the 1690s, French dictionaries included a new term, piéton, a pedestrian. Early references to piétons all involved complaints about badly paved streets and speeding carriages. From the start, the quintessential city walker was fighting for space in an overcrowded cityscape.

Indeed, the Pont Neuf was built just when the use of vehicles of all kinds to get around in Paris was about to skyrocket. And because of the New Bridge's size and its central location, a great many conveyances used it to cross the river. In no time at all, it thus became the poster child for what was quickly perceived to be one of the modern city's greatest ills: the traffic jam.

Indeed, the Pont Neuf was built just when the use of vehicles of all kinds to get around in Paris was about to skyrocket. And because of the New Bridge's size and its central location, a great many conveyances used it to cross the river. In no time at all, it thus became the poster child for what was quickly perceived to be one of the modern city's greatest ills: the traffic jam.

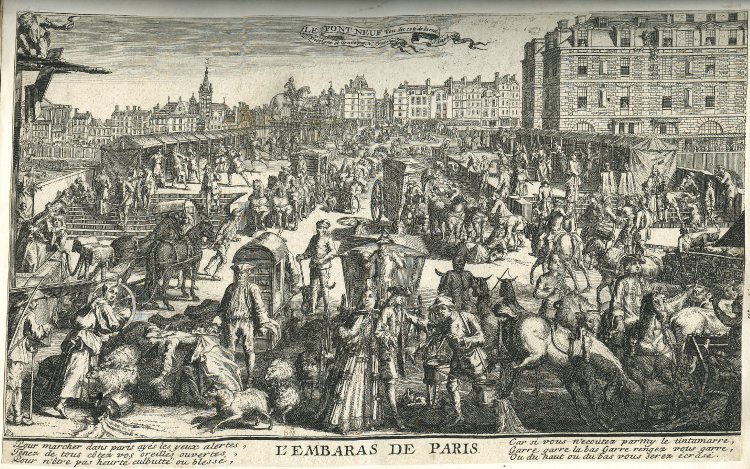

An image from about 1700 is the original depiction of a traffic jam: it has a double title, "The Pont Neuf" and "l'embarras de Paris." In the course of the seventeenth century and particularly in its final decades, that word, embarras, which until then had meant "embarrassment" or "confusion," acquired a new meaning: "The encounter in a street of several things that block each other's way." A new kind of urban "confusion" had taken shape.

Foreign visitors to Paris in the seventeenth century never failed to point out "the ruckus," "the state of perpetual hubbub" that characterized the city. Those who described themselves as "having traveled widely all over Europe" claimed that, in this, Paris had no equal. (One world traveler did say that Paris had a rival for the world's most congested city: Beijing.) They repeated that the growing number of carriages that clogged the city's streets not only made so much noise that it was impossible to hear a vehicle approaching but also went so fast that "pedestrians live in constant fear of being crushed." As one street-wise individual put it: "In Paris, you need eyes on all sides of your head." And visitors reported that one place was the most bustling spot of all, "day and night in perpetual motion": the Pont Neuf.

These visitors were not imagining things: in the second half of the seventeenth century, carriages were taking over. The first carriage had been spotted in Paris in about 1550. (Historian Sauval claimed that it had belonged not to the king or a great aristocrat but to the wife of a wealthy apothecary.) Carriages long remained as scarce as hen's teeth: at the time the Pont Neuf was built, it was said that there were not ten of them in the entire city -- and that the king himself owned but a single one. But in the 1700 edition of his guidebook, Brice claimed that the total had grown to twenty thousand. Many new streets had been added during that half-century; many older streets had been made wider and longer; the city's overall surface had increased. None of this, however, was sufficient to counteract the significant spike in vehicular transport.

It is of course paradoxical that the first thoroughfare in Paris expressly designed to prevent traffic issues came to stand for the overly congested city, but every depiction of the bridge reveals why. The raised walkway was not continued in the central section where the statue was erected. In order to cross the bridge, pedestrians thus had to walk down several steps, move through the middle portion, and walk up steps on the other side. (The elevations were removed in 1775.) That central section, 75 feet wide and with its spectacular view, was the kind of public space the city had never known. It seemed that everyone, and not only those who traveled on foot, wanted to enjoy it -- and that opened the door to complete anarchy.

The bridge had been designed as a multi-lane thoroughfare, wide enough for four carriages to cross at the same moment. Carriages, however, also had to compete for room with sedan chairs, with horse-drawn carts, with riders on horseback; and rules had never been established to indicate how the area should be divided among the different modes of transport. In the foreground of the original image of a traffic jam, we see a water carrier who, because of the buckets draped over his shoulders, takes up a lot of space. There's a shepherd with his dog and his flock of sheep; some of them have broken ranks in order to get around a sedan chair and have knocked over the water being carried home by a working-class housewife. A man tries to help a woman thrown to the ground in the melee. An aristocratic couple is taking it all in, as oblivious to the chickens underfoot as to the sheep hurtling by. It was rush hour on the Pont Neuf.

Nicolas Guerard, L'Embaras de Paris (c.1700)