The Creation of the Pont Neuf

Joan DeJean, How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City (New York: Bloomsbury,2014), pp.15, 21-22, 24.

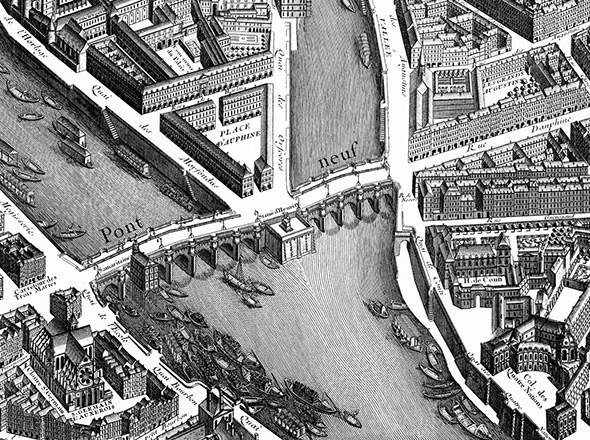

Nowhere was the city's new urban culture more evident than on modern Paris' first great monument, the Pont Neuf. As soon as the New Bridge was opened to the public in 1606, it began drawing record crowds. There, people first relished a sight considered ever since to be essential to the experience of Paris: the perspective over the Seine from a bridge. In 1600, the Seine was Paris' commercial lifeline, used to bring heavy goods into the city. It was little appreciated for its beauty, for the simple reason that it was next to impossible to get a view out over its expanse. Most of the embankments were not yet developed; instead, houses were often built up right to the river's edge. All existing bridges were lined with houses, so there was no vista when you crossed over. Unlike other city bridges such as Florence's Ponte Vecchio or London Bridge, the Pont Neuf was built without houses, and in fact was built with little balconies , almost like boxes at the theater, that encouraged those crossing the Seine to step to the side, lean on the edge, and watch the river flow. Every image of the New Bridge shows the balconies filled with river spectators, captivated by a panorama newly part of the experience of Paris (color insert). And from 1606 on, they had more and more to take in: many of the finest new constructions that were added to the cityscape were built along the Seine, making Paris the first European capital to use the river view to showcase modern architecture and the first capital to highlight the role that could be played by riverbanks in creating a beautiful, unified urban fabric. . . . |

Detail from Turgot's Map of Paris (1734) |

THE I N V E N T IO N OF Paris began with a bridge.

Today, people simply flash an image of the Eiffel Tower to evoke Paris instantly. It's the monument that offers immediate proof that you are looking at the City of Light. In the seventeenth century, the Eiffel Tower's role was played by a bridge: the Pont Neuf [in French “New Bridge]. The New Bridge was Henri IV's initial idea for winning over the people of his freshly conquered capital city, and it managed that daunting task with brio. For the first time, the monument that defined a city was an innovative urban work rather than a cathedral or a palace. And Parisians rich and poor immediately adopted the Pont Neuf: they saw it as the symbol of their city and the most important place in town.

Artists quickly began to turn out images of this new kind of signature monument. Almost all of them are scenes of hustle and bustle, of hurly-burly, positively overflowing with people and activity. They portray urban life as diverse, gritty-fueled by sometimes uneasy excitement. One glance at any of them and you knew a great deal about the sort of place that Paris was becoming.

The New Bridge became the first celebrity monument in the history of the modern city because it was so strikingly different from earlier bridges. It was built not of wood, but of stone; it was fireproof and meant to endure -- it is now in fact the oldest bridge in Paris. The Pont Neuf was the first bridge to cross the Seine in a single span. It was, moreover, most unusually long-160 toises or nearly 1,000 feet -- and most unusually wide-12 toises or nearly 75 feet - far wider than any known city street.

The Pont Neuf was the first major city bridge built without houses lining both sides. Anyone crossing it could take in the sights from the bridge, and Parisians and visitors began a love affair with the river from a viewing platform seventy-five feet wide.

Along each side where earlier bridges had houses, the New Bridge featured instead spaces reserved for pedestrians; they were raised in order to exclude vehicles and horse traffic. We would call them "sidewalks"; they were something that had not been seen in the West since Roman roads and something that had never been seen in a Western city. Add to this the fact that the Pont Neuf was the first bridge whose entire surface was paved, as all the new streets of Paris soon would be, and it's easy to see why pedestrians saw themselves for the first time as kings of the river.

The bridge proved essential to the flow of traffic across Paris: before, just getting to the Louvre from the Left Bank had been a famously tortuous endeavor that, for all those not wealthy enough to have a boat waiting to ferry them across, required the use of two bridges and a long walk on each side. The New Bridge also played a crucial role in the process by which the Right Bank became fully part of the city: in 1600, its only major attraction was the Louvre, whereas by the end of the century, the Right Bank showcased important residential architecture and urban works, from the Place Royale to the Champs-Elysees. In addition, whenever a major event transpired in seventeenth century Paris, it either took place on the Pont Neuf or was first talked about on the Pont Neuf. Nearly two centuries after its completion, author Louis Sebastien Mercier still considered the New Bridge "the heart of the city."

The Pont Neuf set higher standards for European bridges. The city's first pathbreaking public work also had a direct and profound impact on the daily life of Parisians. It introduced them to a new kind of street life, and it transformed their relation to the Seine. The Pont Neuf was never merely a bridge: it was the place where Paris first became Paris, as well as the place where the mod ern city's potential first became evident. . . .

No prior bridge had had to deal with anything like the load the New Bridge was intended to bear -- most significantly, a kind of weight that in 1600 was just becoming a serious consideration: vehicular transport. Earlier cities had only had to contend with transport that was relatively small and light: carts and wagons. In the final decades of the sixteenth century, personal carriages were just beginning to be seen in cities such as London and Paris. Nevertheless, with great foresight, each of Henri IV's documents on the Pont Neuf adds new kinds of vehicles to the list of those to be accommodated. He was thus the first ruler to struggle with what would become a perennial concern for modern urban planning: the necessity of maintaining an infrastructure capable of handling an ever greater mass of vehicles.

Auguste Renoir, The Pont-Neuf (1872)