Background to Early Modern Paris

Joan DeJean, How Paris Became Paris: The Invention of the Modern City (New York: Bloomsbury,2014), pp.6-7, 12.

Paris had become the country's capital and the official residence of the kings of France in 987, but its position was unstable for the following centuries. It was a theater of violence during first the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453) and then the Wars of Religion (1562-98). In 1415, after the French defeat at the battle of Agincourt, their monarchs abandoned the city. In 1436, Charles VII reclaimed it from the English, but throughout the sixteenth century the kings of the Valois dynasty mainly ruled from their chateaux in the Loire valley rather than the Louvre. In 1589, when Henri III was assassinated by a religious fanatic, the Valois dynasty ended. Henri IV, his successor and the first king of the Bourbon monarchy, twice failed to take Paris by force. He finally won over through diplomacy a capital exhausted and ruined by decades of war. The city he entered in 1594 was big -- the largest west of Constantinople -- but in no way a functioning capital. However, Henri IV was a fast worker.

By 1598, he had accomplished the first objective of his reign, peace, by promulgating the Edict of Nantes, which made religious tolerance official state policy, and by

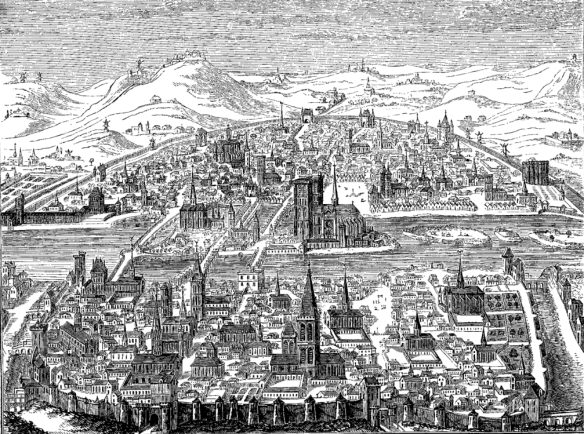

Engraving of Paris 1607 |

signing a treaty with the Spanish. He then reorganized the country's administration. During the Wars of Religion, provincial governments had enjoyed great autonomy. Henri IV began the process, continued by both Louis XIII and Louis XIV, by which Paris fully became the seat of the French government; administrative functions became increasingly centralized, and the French monarchy became increasingly absolute. But it was with his work as a builder that Henri IV changed Paris most profoundly.

Throughout a cityscape devastated by war, Henri IV started ambitious public works projects In the little more than a decade before he was himself assassinated in 1610, he put Paris well on its way to becoming a place that could be billed as "the capital of the universe."

Indeed, the king conceived of his plans for Paris in just such grandiose terms. In March 1601, Paris' municipal government was informed that "His Majesty has declared his intention of making the city in which he plans to spend the rest of his life beautiful and splendid, of making [Paris] into a world unto itself and a miracle of the world." And he quickly put those intentions into action. A contemporary periodical, Le Mercure françois ("French Mercury"), informed its readers that "as soon as [Henri IV] became the master of Paris, you could see construction workers all over the city." Only six years later, the king wrote France's envoy to the Vatican, Cardinal de Joyeuse, with 'news about my buildings." He listed the public works of which he was most proud and concluded: "You will hardly believe what a changed city you'll find."

A century later, the original historian of its municipal governance, Nicolas Delamare, confirmed the king's proud words: before Henri IV, it was as if "no one had done a thing to beautify the city." The list of accomplishments that both the king and his contemporary admirers proudly enumerated as the architectural highlights of his reign always began with the urban works referred to as "the two wonders of France": the Pont Neuf, a bridge that would revolutionize the way European cities related to their rivers, and the Place Royale, today's Place des Vosges, a square that would transform urban public space. Commentators stressed how "at the beginning of Henri IV's reign, Paris had wide stretches of barren terrain-fields, prairies, and swamps, uninhabited and devoid of construction." The king began making empty land into a novel kind of urban landscape, creating in the process "a city completely different from what it had been in 1590," as foreigners and Parisians who returned after even a few years away never failed to point out -- "une ville nouvelle ," a new city.

Paris became ever newer as the century progressed. Henri IV's son, Louis XIII, made far less grandiose plans. But he did see some of his father's most daunting projects through to completion -- in particular, the idea of turning more "barren terrain" into one of the city's most elegant neighborhoods, one that still looks much as it did upon its completion in the early 1640s: today we know it as the Île Saint-Louis. And Louis XIII produced a son whose ambitions for his capital made him truly his grandfather's heir.

Two phrases from the pen of Louis XIV's chief minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, both from 1669, illustrate this. The first is a list of major construction projects that ends: "grandeur and magnificence everywhere." The second could be called the categorical imperative of Louis XIV's monarchy: "This is not a reign that does things on a small scale."

The total terrain built up during Henri IV's reign was in no way comparable to the massive development during the later decades of the seventeenth century. Left Bank , Right Bank, at the city's periphery as much as at its center, edifices (even one as iconic as the Louvre) were then rebuilt, and neighborhoods were redesigned- or invented . This 1677 engraving depicting the remodeling of the Louvre's facade gives a sense of the kind of major construction site then found all over the city. It would have been impossible to walk fifteen minutes in any direction without encountering reminders of the fact that Paris was a city in transition , shaking off its past in a hurry. . . .

Those who described Paris in the seventeenth century consistently evoked the experience of the jostling crowds that characterized a city "absolutely full of people." The first census dates from the end of the eighteenth century; prior to this, there are only estimates of its population. In 1600, there were roughly 220,000 Parisians; in 1650, approximately 450,000. Most now agree that, in 1700, Paris had about 550,000 inhabitants -- slightly more than its only European rival, London, though behind the then most populous cities in the world: the cities we know today as Istanbul, Tokyo, and Beijing .

Francois Dubois, St. Bartholomew Eve

The Slaughter of Protestants By Ultra Catholics in Paris in 1572