Paris in the Early Middle Ages

James H.S.McGregor, Paris from the Ground Up (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009), pp.26-32, 35.

Throughout the fifth century, the empire, under both Latin and Germanic rule, tried to hold on to the territory that had been won centuries before, but without

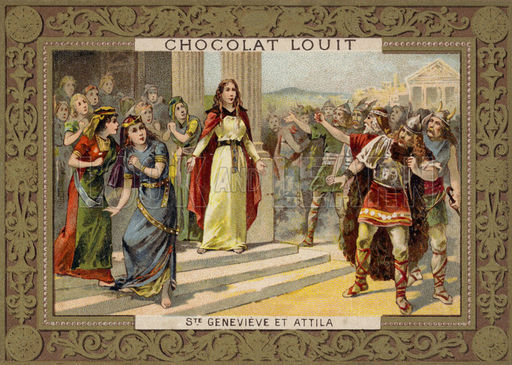

Late 19th or Early Twentieth Century French Chocolate Wrapper Portraying a Very Fanciful Image of the Encounter of St. Genevieve and Attila the Hun

|

success. Tribes whose homes were far beyond the imperial borders made their way through the homelands of Rome's long-term enemies, to strike at the heartlands of the empire. Among the most aggressive and successful of these invaders were the Huns led by the "Scourge of God," Attila. In the late winter of 451, fresh from successful raids into Byzantine territory, he led his troops and allies across the Danube River and west toward Gaul. The Huns attacked and burned cities east of the Rhine, then headed northwest toward Lutetia. Here their advance was turned aside by the woman who would become Saint Genevieve, the patron saint of Paris.

"Hearing that King Attila of the Huns was laying waste to Gaul, the citizens of Paris were wild with fear. They thought that it would be best for them to leave the city and take all their merchandise and belongings to the security of safer places. Genevieve called together the women of the city and persuaded them to begin vigils, prayers and fasts in hopes that they could avert the impending catastrophe. The women agreed to her plan and for several days they remained in the baptistery of the church in prayer, fasting and wakefulness. As Genevieve urged, they continually cal ed on God. She also persuaded the men not to ship their goods out of the city. Now those cities that the Parisians would have chosen as their refuge were ravaged by the furious Huns. Paris itself was saved and through the protection of Christ remained inviolate" (Acta Sanctorum, vol. 1, p. 139).

According to the legend of Saint Genevieve, when Clovis arrived in his new capital, the holy woman was there to greet him. Whenever she interceded on behalf on someone he had sentenced to death, Clovis was willing to forgive. Genevieve died early in the sixth century; the exact year is unknown, though her death is traditionally commemorated on January 3. At her passing, Clovis ordered a basilica to be built in her honor in or near the cemetery where she was buried on the Left Bank. Construction had barely begun at the time of his own death in 511. His queen, Clotilde, carried on the project. The building they created was similar in form to the worship center excavated at Notre Dame, but its purpose was different. This was not a church but a shrine dedicated to the saint, and its main role was to host funeral and commemorative masses and to provide burial spaces near the saints.

Jean-Paul Laurens, Death of Saint-Geneviève (1877) -- A mural in the Panthéon

|

At its founding, the basilica was dedicated to Saint Peter and the Holy Apostles, just as the Apostoleion in Constantinople, where the emperor Constantine and many of his family members were buried, had been. In imitating the dedication and perhaps in planning his own burial in the church, Clovis may have revealed the extent of his imperial and dynastic ambitions. In any case, the apostles were dropped from the title of the church in the seventh or eighth century, and the basilica was referred to informally as Saint Genevieve. After a number of miracles were attributed to her intervention, the name was officially changed in the eleventh century. The basilica was supplanted in the eighteenth century by the Pantheon and dismantled in the early years of the nineteenth century.

The hilltop on which the Romans had planted their colony of Lutetia eventually took its new name from the enormous abbey that began to grow up around the tomb and basilica of Saint Genevieve. The character of Paris had changed entirely by then. The lie de la Cite was its center, and the Roman ruins on the Left Bank had either disappeared or been engulfed by other structures. The Roman aqueduct had long ceased to carry water. Even the grid of roads that the Romans had so carefully laid out had all but disappeared into a web of streets that met for the most part at odd angles and ran obliquely through old intersections. The great exception was the road now known as the Rue Saint Jacques. Originally a pre-Gallic highway, the road still ran into Paris and straight across the lie de la Cite. Its Christian name, however, indicated a new purpose in traveling the old road. International trade was no longer its major burden. Instead, it carried pilgrims along the great road to Compostela and the shrine of Saint Jacques, who is called Santiago in Spanish. . . .

The legend of Saint Genevieve records a number of rather meager miracles during these Viking incursions. In the  two periods of greatest threat, the late 850s and the winter of 886, the saint's relics were removed from the unprotected Left Bank basilica and carried to castles outside Paris. Despite Genevieve's success against the Huns, no one seemed to expect her relics to withstand or divert the Vikings. Nevertheless, an abundance of miracles did occur both while the relics were being taken away for safe keeping and more commonly during the joyous processionals that brought the relics back to the basilica. The importance of these miracles was not so much their scale but their role in the creation of a local saint who shared with the people of Paris the ongoing history of the city. Her continuing legend made her the focus of a kind of devotion that blended religious veneration and local pride. Saints of this kind were especially important in the Middle Ages as cities established their identity both locally and in the minds of competitors. A city with an illustrious saint gained preeminence.

two periods of greatest threat, the late 850s and the winter of 886, the saint's relics were removed from the unprotected Left Bank basilica and carried to castles outside Paris. Despite Genevieve's success against the Huns, no one seemed to expect her relics to withstand or divert the Vikings. Nevertheless, an abundance of miracles did occur both while the relics were being taken away for safe keeping and more commonly during the joyous processionals that brought the relics back to the basilica. The importance of these miracles was not so much their scale but their role in the creation of a local saint who shared with the people of Paris the ongoing history of the city. Her continuing legend made her the focus of a kind of devotion that blended religious veneration and local pride. Saints of this kind were especially important in the Middle Ages as cities established their identity both locally and in the minds of competitors. A city with an illustrious saint gained preeminence.

Saint Genevieve