Paris-Lutetia: From earliest times to c. 1000 (1):

The Decline and Fall of Roman Paris

Colin Jones, Paris: Biography of a City (New York: Viking, 2005), pp.12-13,15-17.

The rural character of greater Lutetia increased over the course of the third and fourth centuries, as Roman power wavered, declined and was finally extinguished.

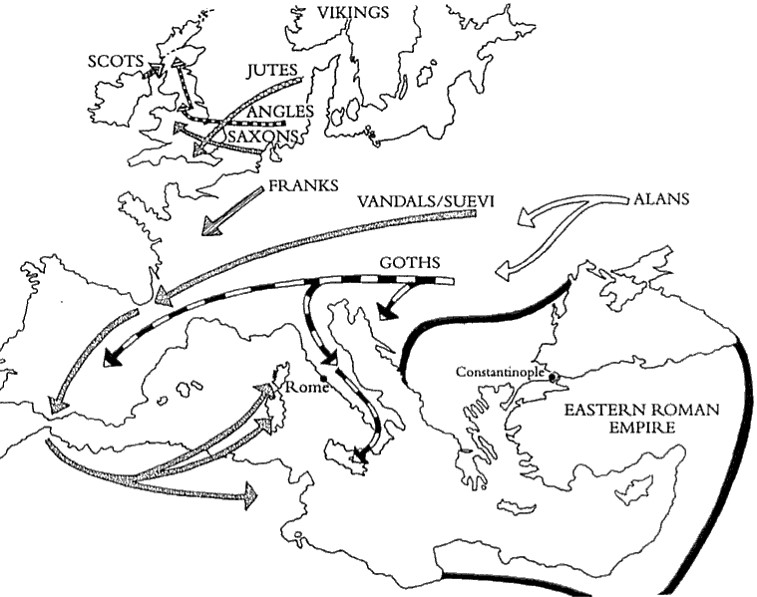

Expansion of the Germanic Tribes into the Roman Empire in the 5th Century |

From late in the second century, plundering barbarian incursions from beyond the limes were starting to spread insecurity across Gaul. As early as 162 and 174 raiding highlighted the danger, but it was really from the late third century that the problem became acute throughout the province. The attacks of the Germanic Alamans and Franks in 275 caused damage to sixty Gaulish cities, Lutetia included. This led, a little after 300, to the fortification both of the Ile de la Cite and of an indeterminate area around the forum, using stone from more undefendable buildings. The growing practice of individuals burying hoards of coins and other valuables demonstrated the psychological impact of the barbarian threat. . . .

Despite these worrying signs, the invasions seem to have affected Paris relatively lightly by comparison with other northern cities, and problems were not seen as serious enough to prevent individuals building residences outside the fortified areas. Though slightly contracted, the urban tissue which had developed under the pax romana [the Roman peace] stayed essentially intact, albeit probably invaded by weeds and nettles. Furthermore, Lutetia also came to develop a measure of latter-day strategic importance . While the limes had been watertight, it was possible for Roman military forces to police the frontier based in cities close to Germany such as Trier. Once the frontier had begun to falter, there was much to be said for a rearguard location such as Lutetia, which was too far distant to be a first target for invading raiders. The excellent system of roads and rivers emanating from the city facilitated the swift movement of troops to any hotspot. It also provided efficient lines of military food supply through to the Cambresis, the Beauce and Poitou. Wine production (noted by Emperor Julian) established itself in the region, probably even before the decision of Emperor Probus ( 276-82) to lift the age-old ban on vine cultivation outside Italy. A Lutetian military camp was established in an area on the Left Bank out to the south-east on the road to Italy. A fleet was also stationed in the city to ferry troops along the river system to points where disorder threatened . The city's development into a garrison city offered excellent opportunities to the boatmen of the Parisii: the nautes doubtless continued to prosper.

These must have been the overwhelming strategic reasons for the Roman general Julian's choice of the city as his winter headquarters when he was sent to Gaul to combat Germanic raiding in the late 3 50s. He established basilica on the Île de la Cité [the island at the middle of the town], whose importance seems to have been growing at this time: the city's port was also located on the island. In 360, in an act which was to prove of some significance in Lutetia's later history, Julian was acclaimed Roman emperor by his troops. The latter were mutinous at the threat of being transferred to fight on Rome's eastern, Illyrian frontier -- torn from their families, as they put it, in 'a state of nakedness and want'. The legionaries raised a reluctant Julian on a footsoldier's shield in acclaim -- a ritual as much Germanic as Roman -- and, in the absence of a suitable diadem, coiffed him with a standard-bearer's insignia. The new emperor died three years later, but one of his successors, Valentinian I, also quartered here in 365-6 during campaigns against the barbarians, giving extra sheen to the imperial aura of Lutetia. . . .

Emperors Julian and Valentinian in the late 350s and early 360s enjoyed a measure of success in pushing back German tribes -- notably the Alamans and the Franks -- across the limes. The shift of the military command from Paris to Trier late in the fourth century suggested a greater sense of security in the region of the limes. However, the shades of the pax romana flattered only to deceive, as, in the fifth century, Roman power collapsed completely. The development of a dual empire based in Rome and Constantinople failed to rally imperial forces in the west. In 4ro Rome was sacked by the Visigoths, and the division between the eastern and western empires was definitively enshrined. Even before that, in 406, the Roman defensive frontier in the north-east had punctured like a balloon, as hordes of Germanic invaders swarmed across the limes, effectively ending the Roman provincial system throughout Gaul. The Burgundes settled in eastern France, the Alamans in Alsace, the Sueves and Vandals in Spain while the Visigoths crossed from Italy into south-western France, establishing a kingdom in the Toulouse area which Roman imperial authorities were forced to recognize in 416. In swathes of northern and north-eastern France, it was the Franks who were the dominant force.

Prominent among a loose confederacy of tribes answering to the name of Franks were the Salian Franks . . . Losing its sense of itself as Roman Lutetia, Paris was gaining a new identity, in which religion played a key role. Christianity had arrived, and was durably etching itself on the face of the city. Subsequent church tradition had it that the first Christian community in the city had been founded by Saint Denis, who was widely believed to be the Denis the Areopagite mentioned in the New Testament as a follower of Saint Paul. This tradition was based on a confusion of Denises. The Parisian Saint Denis was probably a Christian missionary expedited to the region towards the end of the third century. He worked clandestinely, since Christianity's intolerant monotheism was perceived as threatening to the Roman cult: emperors Decimus (249-51) and Valerian ( 253-60), for example, had launched bouts of severe persecution. Denis was executed, possibly in 272. His death was the occasion for the miracle on which his canonization was to be based: decapitated on the slopes of Montmartre or Mons Mercurii, he was alleged to have picked up his head and walked with it to the place of his burial, over which the abbey of Saint-Denis was subsequently built. The fortunes of Christianity improved drastically when, by the Edict of Milan of 313, Emperor Constantine made Christianity the religion of the state. Although sporadic persecution of Christian communities did not cease --Lutetia's champion Emperor Julian, for example, was a militant anti-Christian -- by the early fifth century Christianity was secure. Henceforward it was pagans and heretics who were on the receiving end of persecution.

"Dress of All Nations -- the Franks" (1882)