The Construction of Notre Dame

James H.S. McGregor, Paris from the Ground Up (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009), pp.44-46.

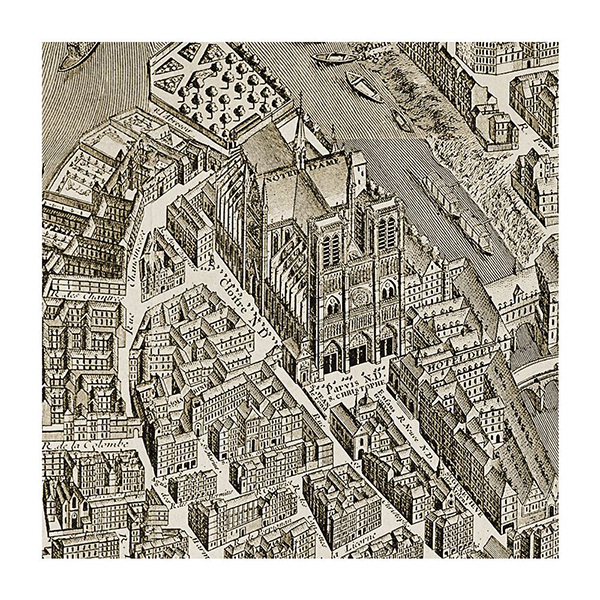

A building on the scale that the canons projected demanded a site far larger than the old church of Our Lady and the basilica of Saint Stephen combined. Maurice de  Sully's solution was ingenious. Rather than reach westward from these old sites into the thickly settled neighborhoods of the island where demand kept real estate prices high, he decided to expand in the other direction, toward the east. The canons owned a small island just upstream from the lie de la Cite at what would be the apse end of the new church. By driving piles and adding rubble to fill in the channel between them, the two islands could be linked. The work progressed quickly, and the site was ready for the builders by 1160.

Sully's solution was ingenious. Rather than reach westward from these old sites into the thickly settled neighborhoods of the island where demand kept real estate prices high, he decided to expand in the other direction, toward the east. The canons owned a small island just upstream from the lie de la Cite at what would be the apse end of the new church. By driving piles and adding rubble to fill in the channel between them, the two islands could be linked. The work progressed quickly, and the site was ready for the builders by 1160.

The bishop also had plans for the area in front of the new cathedral, and to carry them through he could not avoid buying and demolishing some houses. Just as he had anticipated, the few structures he was forced to purchase cost enormous amounts of money, and decades passed before their transfer was complete. Finally, these island properties were leveled to create a small open square in front of the church, the ancestor of the now much larger area-created in the nineteenth century by Baron Haussmann -- called the parvis of Notre Dame. To join the church and its little square to the main road crossing the island, builders cut a narrow street westward. This street, which was on a direct line with the center door of the cathedral, has since been absorbed into the expanded parvis, but its trace is preserved in white marble in the pavement there. The roadway, though small, extended the vista from which the full height of the church could be seen and appreciated.

A building on such a grand scale required enormous amounts of raw material of suitable strength and durability. While the site was being prepared, workers set about quarrying stone. Some of it was probably pilfered from Roman ruins that had not been fully stripped of their materials when the island was fortified. But the bulk of the limestone was cut from outcrop pings on a little hill opposite Mont Saint Genevieve . In an age when transportation of heavy cargoes was difficult and expensive, having convenient access was important. The blocks were brought down to the banks of the now-buried River Bievre and then floated on barges to the Seine.

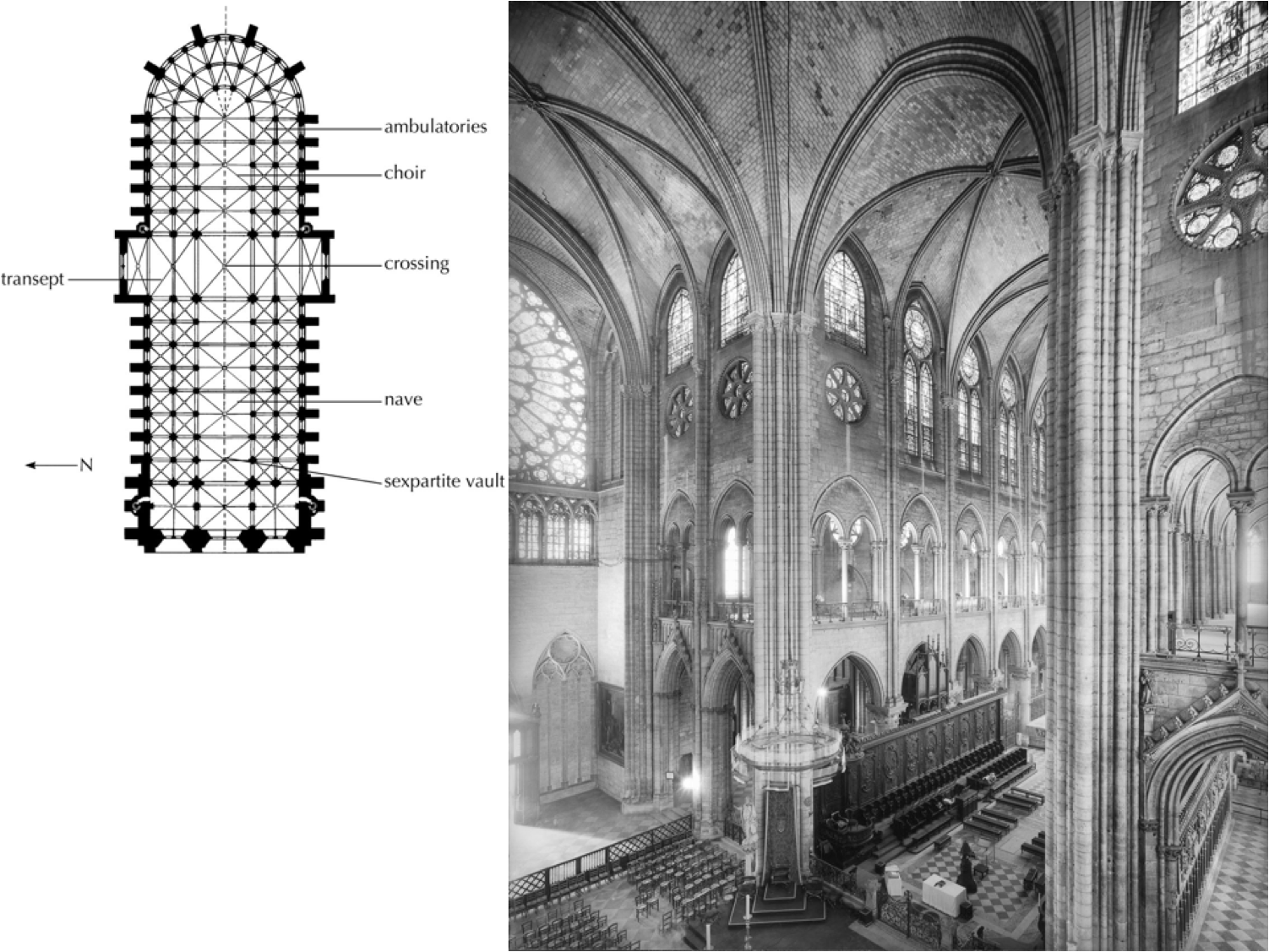

Work began at the eastern end of the church, the choir. This is where the altar stood and the canons heard mass. If we think of the construction of Gothic cathedrals as the work of centuries, the building of Notre Dame seems remarkably fast. The first stones were laid in 1163, and by 1182 the choir and its double aisles were complete . The altar was consecrated and services for the canons began. During the next twenty years, workers finished all but the two westernmost bays of the nave. Work on those bays was deliberately postponed so that the western facade could be constructed from both sides. When the facade was tall enough to clear the side aisles, the nave was completed and the two separately built sections were joined together.