Philip August and the Development of Medieval Paris

Colin Jones, Paris: Biography of a City (New York: Viking, 2005), pp.45-48.

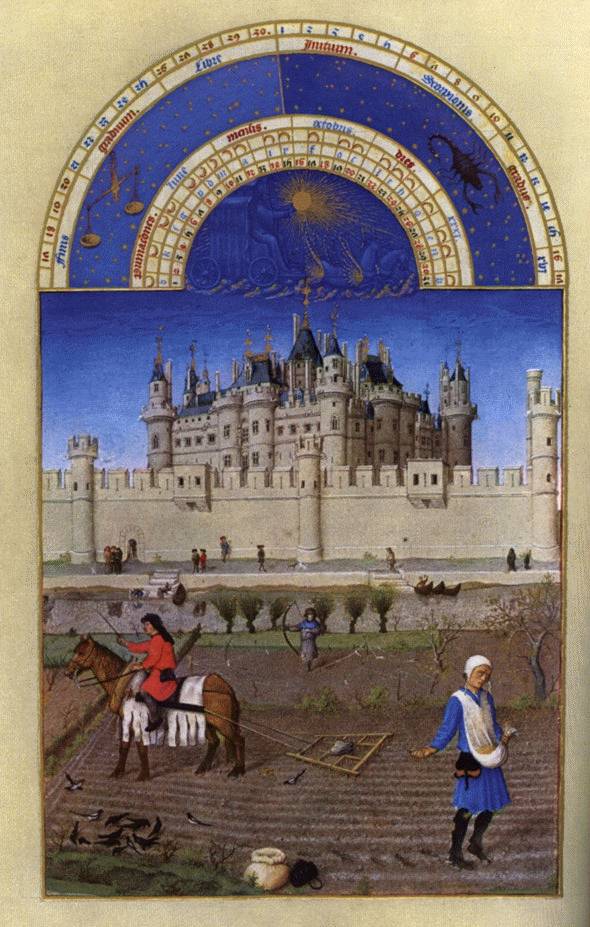

Philip Augustus [king 1165-1223] resided not only at the old royal palace on the Cite, but also the fortresses which he developed at the Louvre and at Vincennes, as well as at the abbey of SaintGermain-des-Pres and the Temple. Despite this itinerant quality -- which would remain a feature of the monarchy throughout the medieval and early modern period -- the idea was gaining ground that royal authority was fixed and stabilized in the kingdom's capital. Indeed, the phrase caput regni ('head of the kingdom', 'capital') became current from precisely this period. By the early fourteenth century, the idea that 'the city of Paris is, as Rome was, the common fatherland' was gaining currency.

"October" from the Duc de Berry's Book of Hours (1412-1416) The building in the background is the Louvre as it existed as appeared in the 15th century. |

The deliberate use of comparisons between Rome and Paris -- which Philip Augustus exemplified in his adoption of the imperial name -- was intended to bolster the dynasty's claims to unfettered sovereignty. Philip required his capital to be as strikingly associated with his own power as Rome had been for Augustus. This Roman and imperial theme was increasingly evident in dynastic propaganda. It interwove with an older theme, which pictured Paris as having been founded by descendants of survivors from the fall of Troy. One version of this myth of origins had it that the founder of the city had been King Priam's son Paris. Others provided a different trajectory which fitted in with the idea that the Franks as a people had originally been

descendants of a Trojan diaspora.

Philip Augustus and his successors thus strove to make the capital a place worthy of such distinguished origins. The city came to house the state's embryonic administrative structures as well as the royal household. The royal seal had been lodged permanently in Paris since the time of Louis VI, and it was used to certify state documents in the physical absence of the king. . . .The royal chancery and the Parlement of Paris -- which from the second half of the thirteenth century was the kingdom's high court of law -- shared the palatial premises on the Île de la Cité too. Justice was now dispensed in the king's name from Paris and no longer merely a personal attribute of the ruler.

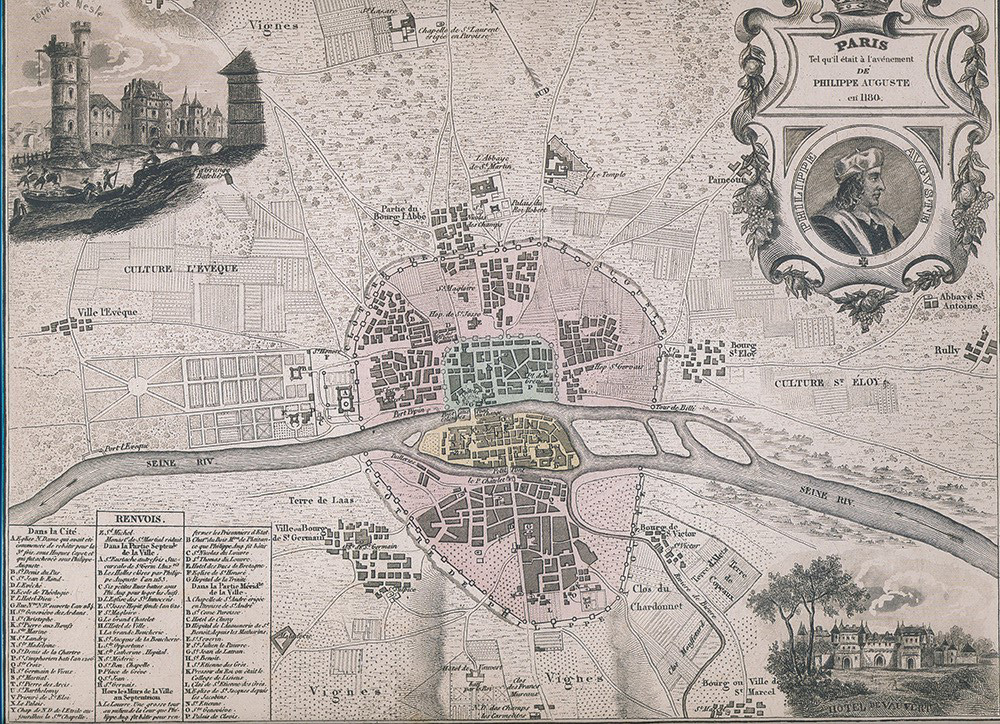

Perhaps the most striking and influential way in which Philip Augustus helped to change the physiognomy of Paris in line with its vocation as a royal capitaI was his decision to build a fortified wall around its perimeter. The wall of Philip Augustus was constructed on the Right Bank between 1190 and 1209 and on the Left between 1200 and 1215. Whereas the merchant class contributed to the building of the Right Bank wall, the extension on the south of the river was done entirely at the crown's expense-and somewhat on the cheap. Rabelais's later contention that 'a cow's fart' would bring the whole thing tumbling down was an exaggeration, but one which highlighted the limited long-term military effectiveness of the perimeter wall on the Left Bank. Yet in the short term, the wall's military purpose is more than evident. Over five kilometres in length, three metres wide at the base, between six and eight metres high, the wall was studded with some seventy-one towers, mostly at an interval of between sixty and eighty metres. Neat engineering conducted water from the Seine and from rivulets to the north and east to supply a moat round the Right Bank wall; the Left Bank had to make do with dry defences. The wall had twelve heavily defendable gates, marking the main entry points into the city. Following an incident when the king was -- the chroniclers relate -- mightily offended by the stench of Parisian mud and effluent passing his window, he ordered that the main pathways leading to each of the gates be paved. On the wall's western edge, overlooking the Seine, and facing out towards the direction of Anglo-Norman power, the fortress of the Louvre was constructed, its central tower some thirty metres high. The Louvre made the existing fortifications on the Île de la Cité obsolete. No matter, they were maintained, and indeed Philip and his successors strengthened the fortifications of the palace and of the fortresses overlooking the Grand Pont linking the Right Bank to the Île de la Cité (the Grand Chatelet) and over the Petit Pont (the Petit Chatelet). . . .

The wall was never put militarily to the test, and was in time encompassed -- indeed virtually lost sight of -- within the growing city. The Left Bank wall remained functional for many centuries, but on the Right Bank the creation of the Wall of Charles V in the late fourteenth century made the Philip Augustus Wall obsolete and redundant north of the Seine. The gates were gradually demolished, and fragments of the wall were often incorporated into subsequent buildings, thus entering a kind of memory deep-freeze from which only disparate pieces have been released. The hundred metres or so of wall on the Rue des Jardins-Saint-Paul [these Roman numerals refer to the arrondissements or districts that Paris is divided into] in the Marais were uncovered by demolition and 'conservation' work in what was a poor and overcrowded area in 1946, while the restoration and public viewing of the base of one of the ramparts under the Tower of John the Fearless on the Rue EtienneMarcel dates from restoration work done in the 1990s.

Despite its rather meagre functionality, the Philip Augustus Wall has played an extremely important role in the history of the city in a number of ways. It highlighted to the king's fellow European monarchs his determination to make his capital a key piece in his general system of power. To some extent he built the monarchy into the wall -- not merely by commanding its construction and contributing to its cost, but also by placing his royal palace, the Louvre, at one of the western limits of the wall. . . .

Furthermore, building the wall was a way of inhibiting external expansion and stimulating the consolidation of undeveloped land within the walls. Intra muros [within the walls] agricultural and wasteland . . . provided potential food supply in time of siege, but was also a site for urban infill. It likely that all present-day streets within the wall on the Right Bank d been laid out by the end of the thirteenth century (with the numerically small exception of nineteenth-century Haussmannian additions). . . .