Viking Invasions

James H.S.McGregor, Paris from the Ground Up (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009), pp.33-35

The descendants of Charlemagne squared off in the same protracted dynastic warfare that had engulfed the Merovingians. But by the ninth century, institutionalized fratricide had become considerably more costly. A new and powerful force from the north was entering the region, ready and able to take full advantage of its political instability. Like the barbarian tribes that came before them, Norse raiders appeared suddenly and inexplicably along the fringes of Europe. Their first recorded raid took place in 787, but the beginning of two centuries of Viking invasions is usually dated to June 8, 793, when dragon-prowed ships suddenly beached at the abbey of Lindisfarne on the northeast coast of England. From that year onward the pillagers returned every summer to coastal villages and towns along the North Sea and Atlantic . In time their ships entered the Mediterranean and traveled as far as the Black Sea. Eventually the raiders turned colonizers, and Viking or Norse kingdoms were established in Sicily, northern France, England, Kiev, and Novgorod and on islands throughout the North Atlantic. From their colonies in Iceland and Greenland, they made a precocious and unsuccessful bid to colonize North America.

fratricide had become considerably more costly. A new and powerful force from the north was entering the region, ready and able to take full advantage of its political instability. Like the barbarian tribes that came before them, Norse raiders appeared suddenly and inexplicably along the fringes of Europe. Their first recorded raid took place in 787, but the beginning of two centuries of Viking invasions is usually dated to June 8, 793, when dragon-prowed ships suddenly beached at the abbey of Lindisfarne on the northeast coast of England. From that year onward the pillagers returned every summer to coastal villages and towns along the North Sea and Atlantic . In time their ships entered the Mediterranean and traveled as far as the Black Sea. Eventually the raiders turned colonizers, and Viking or Norse kingdoms were established in Sicily, northern France, England, Kiev, and Novgorod and on islands throughout the North Atlantic. From their colonies in Iceland and Greenland, they made a precocious and unsuccessful bid to colonize North America.

Paris should have been far enough from the coast to be safe from these sea-faring raiders, but the Seine, the city's great thoroughfare and the source of its prosperity, became a dangerous asset in the Viking era. The raiders began to attack towns along the lower Seine valley in 820. In May 841 a larger force looted and took captives upriver. Sixty-eight of their prisoners were ransomed by the monks of the abbey of Saint Denis on the northern outskirts of Paris. Four years later a fleet estimated at 120 Viking ships reached the city. From the river they laid siege to its island garrison. Unable to drive the invaders away by force, King Charles the Bald paid an enormous ransom.

In the mid-850s, Charles abandoned his policy of appeasement, and his soldiers defeated the Norsemen. But the tide turned again in the Vikings' favor in 858, when their combined forces led retaliatory raids against towns surrounding Paris that Charles's soldiers could no longer protect. Vikings plundered the city of Chartres and executed its entire population. When they again threatened Paris, Charles bought them off as before. But when the king became entangled in a dynastic war with his brother, the Vikings took advantage of his distraction and raided more freely. From well-established safe harbors in the lower Seine valley, they began to ravage the countryside frequently and in greater numbers.

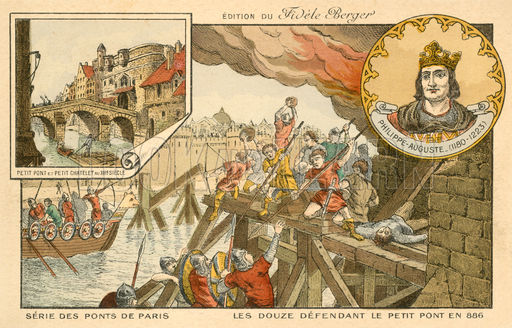

Educational Card from France Teaching about the Viking Invasion, Late 19th Early 20th Century |

In 885 a force of Norsemen left their bases near the modern city of Le Havre and marched ahead of their fleet through the countryside, pillaging and burning. They took Reims in late July and in November overwhelmed a Frankish garrison blocking the river below Paris. At the end of the year they attacked the city from both the land and the river. After the raids of the 850s, Charles the Bald had built a bridge between the lie de la Cite and the right bank more or less where the Pont Neuf is today. The bridge had limited use as a connector; its main task was control of the river. Military engineers had designed two towers at its ends, but when the Viking raiders appeared, the tower on the right bank was still incomplete and came under immediate attack. Citizens and soldiers reinforced the tower with a wooden rampart, which, surprisingly, held for months. Unfortunately for the defenders of the city, a flood in early February washed away the bridge. Facing no impediment, dragon ships quickly filled the channel between the lie de la Cite and the right bank. The right bank tower was overwhelmed and its defenders slaughtered. The fortified island remained the only sanctuary for the terrified Parisians. The Vikings ramped up their attacks.

|