An Overview of Paris -- Origins to 1200

"Introduction," (excerpts) from James H.S. McGregor, Paris from the Ground Up (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009), pp.2-4

The long strand of the city's history that eventually threaded the needle's eye of Revolution began during the early years of Roman colonization , in a Gallic fortress sheltered by marshland at a bend of the River Seine. A trans-European trade path that crossed the river near this settlement distinguished it from the many similar towns upriver and down. In a vain effort to starve out Caesar's legions, the local Gauls -- the Parisii -- set their own town on fire and in a single night destroyed it so completely that no physical trace has ever been found. The victorious Romans built a colony on the sloping southern bank of the river well uphill from the lowlands the Gauls preferred, and the old trade path became a major road through its center. Lutetia -- primitive Paris -- was a Roman town, but its inhabitants were ethnically not all l that different from the tribesmen who had resisted Caesar's assault.

In the second and third centuries AD, the increasingly muddled policies of the empire's distant rulers began to affect frontier colonies like Lutetia. Foreign invaders surged into territories that the center was too weak or too preoccupied to defend. To save themselves, the Parisii moved downhill to the most easily defensible part of their city. This was an island -- now called the Ile de la Cité -- located a bit off-center in the main channel of the Seine. Dressed stones that had once been seats in Lutetia's theater or retaining wall Is beneath its forum became raw material for a defensive perimeter. When Roman imperial armies wintered in the city during the fourth century, their command post was a modest palace on that protected island. When Christian missionaries brought their new religion to Paris, it too was headquartered on the Ile de la Cité.

The name Lutetia died with the Roman hillside colony, and for centuries Parisians remained confined within the narrow limits of their island sanctuary. Many kingdoms that embraced but largely ignored Paris rose and fell in the half millennium between 300 and 800 AD. For a brief period during the reign of Charlemagne, the city was absorbed within a realm that insulated and protected it. But shortly after its founder's death in 814, Charlemagne's dynasty began to collapse under the weight of its own rules of inheritance.

Late in the ninth century, a new foreign enemy took advantage of the endless dynastic struggles among successive rulers. For the next two centuries, Norse raiders threatened the entire European coastline, and Paris, with its navigable river emptying into the English Channel, was as vulnerable as coastal cities. Without effective royal leadership, defense of the city fell to the bishops and the highest ranking civilian leaders, the counts of Paris. Together, they resisted the wave of invaders, and from one generation to the next their influence grew. In July 987 one of the counts -- Hugh Capet -- became king of France. Though his territory was small, his status was grand. Over time the king and his successors came to understand the city as a reflection of royal power and authority.

Under a steady succession of kings whose abilities ranged from outstanding to mediocre, the people of Paris multiplied. The countryside was fertile, and the Seine brought the goods of the region to the doorsteps of the rich and powerful. Business began to concentrate around the Place de Grève on the northern bank, just opposite the upstream end of the Ile de la Cité. As this commercial quarter grew inland street by street, the Left Bank, to the south, teemed with students, drawn by the growing reputation of Paris's schools. Throughout the city, the towers of Gothic churches expressed the taste for architectural novelty as well as the religious aspirations of Parisians.

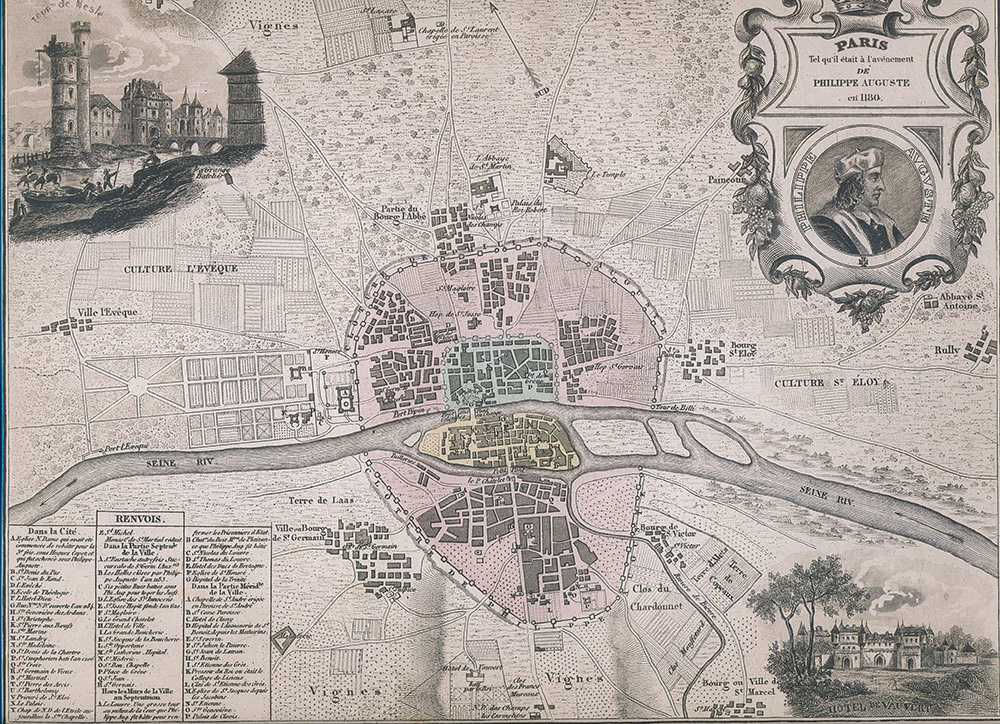

Paris in the 12th Century