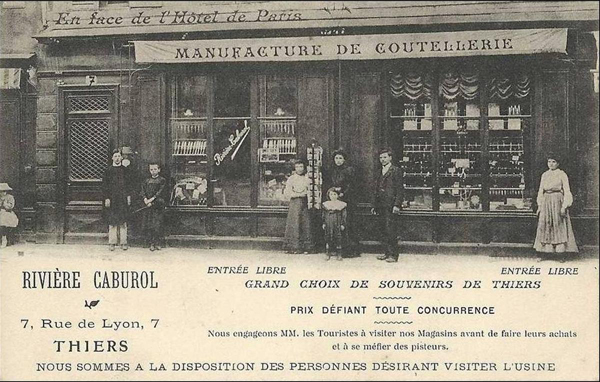

An Older Way of Selling Goods

From Emile Zola, Au Bonheur des Dames (Ladies Paradise)

Denise, Jean, and Pepe, orphans just arrived from the Provinces, have been dazzled by the displays in the windows of a giant department store named Au Bonheur des Dames -- Ladies Paradise -- an institution clearly modeled after the real Au Bon Marché store. Tearing themselves away with difficulty, they find their way to the shop and apartment of their uncle Bandu, with whom they will be living. Here is a description of his establishment, one of the traditional shops that was now in competition with the new department store.

" What about uncle ? " asked Denise, suddenly, as if just waking up. " We are in the Rue de la Michodiere," said Jean. " He must live somewhere about here."

They raised their heads and looked round. Just in front of

them, above the stout man, they perceived a green sign-board

bearing in yellow letters, discoloured by the rain :  "The

Old

Elbeuf. Cloths, Flannels. Baudu, late Hauchecornei." The

house, coated with an ancient rusty white- wash, quite flat and

unadorned, amidst the mansions in the Louis XIV. style which

surrounded it, had only three front windows, and these windows,

square, without shutters, were simply ornamented by a

handrail and two iron bars in the form of a cross. But amidst

all this nudity, what struck Denise the most, her eyes full of

the light airy windows at The Ladies' Paradise, was the

ground-floor shop, crushed by the ceiling, surmounted by a

very low storey with half-moon windows, of a prison-like

appearance. The wainscoting, of a bottle-green hue, which

time had tinted with ochre and bitumen, encircled, right and

left, two deep windows, black and dusty, in which the heaped-up

goods could hardly be seen. The open door seemed to

lead into the darkness and dampness of a cellar.

"The

Old

Elbeuf. Cloths, Flannels. Baudu, late Hauchecornei." The

house, coated with an ancient rusty white- wash, quite flat and

unadorned, amidst the mansions in the Louis XIV. style which

surrounded it, had only three front windows, and these windows,

square, without shutters, were simply ornamented by a

handrail and two iron bars in the form of a cross. But amidst

all this nudity, what struck Denise the most, her eyes full of

the light airy windows at The Ladies' Paradise, was the

ground-floor shop, crushed by the ceiling, surmounted by a

very low storey with half-moon windows, of a prison-like

appearance. The wainscoting, of a bottle-green hue, which

time had tinted with ochre and bitumen, encircled, right and

left, two deep windows, black and dusty, in which the heaped-up

goods could hardly be seen. The open door seemed to

lead into the darkness and dampness of a cellar.

That's the house," said Jean.

" Well, we must go in," declared Denise. " Come on, Pepe."

They introduce themselves to their uncle, who must decide whether to take them in. Meanwhile Zola provides more description of Bandu's shop.

Not a customer had been in to interrupt this family discussion; the shop remained dark and empty. At the other end,the two young men and the young women were still working, talking in a low hissing tone amongst themselves. However, three ladies arrived,and Denise was left alone for a moment. She kissed Pepe with a swelling heart, at the thought of their approaching separation. The child, affectionate as a kitten, hid his head without saying a word. When Madame Baudu and Genevieve returned, they remarked how quiet he was. Denise assured them he never made any more noise than that, remaining for days together without speaking, living on kisses and caresses. Until lunch- time the three women sat and talked about children, housekeeping, life in Paris and life in the country, in short, vague sentences, like relations feeling rather awkward through not knowing one another very well. . . .

Now and again a few customers came in ; a lady,then two others appeared, the shop retaining its musty odour, its half light, by which the old-fashioned business, good-natured and simple, seemed to be weeping at its desertion. But what most interested Denise was The Ladies' Paradise opposite, the windows of which she could see through the open door. The sky remained clouded, a sort of humid softness warmed the air, notwithstanding the season; and in this clear light, in which there was, as it were, a hazy diffusion of sunshine, the great shop seemed alive and in activity.

Denise began to feel as if she were watching a machine working at full pressure, communicating its movement even as far as the windows. They were no longer the cold windows she had seen in the early morning ; they seemed to be warm and vibrating from the activity within. There was a crowd before them, groups of women pushing and squeezing, devouing the finery with longing, covetous eyes. And the stuffs became animated in this passionate atmosphere: the laces fluttered, drooped, and concealed the depths of the shop with a troubling air of mystery ; even the lengths of cloth, thick and heavy, exhaled a tempting odour, while the cloaks threw out their folds over the dummies, which assumed a soul, and the great velvet mantle particularly, expanded, supple and warm, as if on real fleshly shoulders, with a heaving of the bosom and a trembling of flie hips. But the furnace-like glow which the house exhaled came above all from the sale, the crush at the counters, that could be felt behind the walls. There was the continual roaring of the machine at work, the marshalling of the customers, bewildered amidst the piles of goods, and finally pushed along to the pay-desk. And all that went on in an orderly manner, with mechanical regularity,quite a nation of women passing through the force and logic of this wonderful commercial machine.

Denise had felt herself being tempted all day. She was bewildered and attracted by this shop, to her so vast, in which she saw more people in an hour than she had seen at Gornaille*s in six months ; and there was mingled with her desire to enter it a vague sense of danger which rendered the seduction complete. At the same time her uncle's shop made her feel ill at ease ; she felt an unreasonable disdain, an instinctive repugnance for this cold, icy place, the home of old-fashioned trading. All her sensations — her anxious entry, her friends' cold reception, the dull lunch eaten in a prison-like atmosphere, her waiting amidst the sleepy solitude of this old house doomed to a speedy decay — all these sensations reproduced themselves in her mind under the form of a dumb protestation, a passionate longing for life and light. And notwithstanding her really tender heart, her eyes turned to The Ladies' Paradise, as if the saleswoman within her felt the need to go and warm herself at the glow of this immense business.

" Plenty of customers over there!" was the remark that escaped her.

But she regretted her words on seeing the Baudus near her. Madame Baudu, who had finished her lunch, was standing up, quite white, with her pale eyes fixed on the monster; every time she caught sight of this place,a mute, blank despair swelled her heart, and filled her eyes with scalding tears. As for Genevieve, she was anxiously watching Colomban, who, not supposing he was being observed, stood in ecstasy, looking at the handsome young saleswomen in the dress department opposite,the counter being visible through the first fioor window. Baudu, his anger rising, merely said ; ** All is not gold that glitters. Patience ! "

The thought of his family evidently kept back the flood of rancour which was rising in his throat A feeling of pride prevented him displaying his temper before these children, only that morning arrived. At last the draper made an effort, and tore himself away from the spectacle of the sale opposite.