Emile Zola, Au Bonheur des Dames (Ladies Paradise) (1882)

Emile Zola (1840-1902) believed that the function of a writer was to capture the reality of the society around him. He did extensive research about the topics of his novels, and his works often provide fascinating insights into the world he lived in.

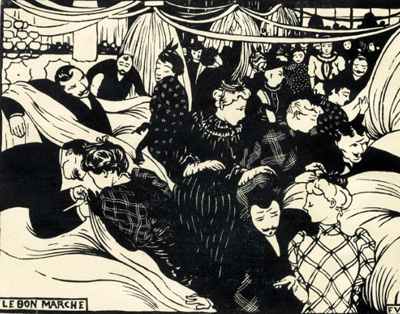

In Au Bonheur des Dames Zola set out to depict the impact of a new phenomenon, the department store, on his contemporaries, particularly on Parisian women. He gave a fictitious name to the store at the center of his novel , but it was clearly model after Au Bon Marche, the first full fledged department in Paris (and quite likely in the world). Here is part of the opening passages of the work. A young woman and her brothers have just arrived in Paris from the countryside, and they are immediately confronted with a brand new palace of consumption.

Denise had walked from the Saint-Lazare railway station, where a Cherbourg train had  landed her and her two brothers, after a night passed on the hard seat of a third-class carriage. She was leading Pepe by be hand, and Jean was following her, all three fatigued after the journey, frightened and lost in this vast Paris, their eyes on every street name, asking at every corner the way to the Rue de la Michodiere, where their uncle Baudu lived. But on arriving in the Place Gaillon, the young girl stopped short, astonished.

landed her and her two brothers, after a night passed on the hard seat of a third-class carriage. She was leading Pepe by be hand, and Jean was following her, all three fatigued after the journey, frightened and lost in this vast Paris, their eyes on every street name, asking at every corner the way to the Rue de la Michodiere, where their uncle Baudu lived. But on arriving in the Place Gaillon, the young girl stopped short, astonished.

' Oh! look there, Jean," said she; and they stood still, nestling close to one another, all dressed in black, wearing the old mourning bought at their father's death. She, rather puny for her twenty years, was carrying a small parcel; on the other side, her little brother, five years old, was clinging to her arm ; while behind her, the big brother, a strapping youth of sixteen, was standing empty-banded.

'' 'Well," said she, after a pause, ''that is a shop!"

They were at the corner of the Hue de la. Michodiere and the Rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin, in front of a draper's shop, which displayed a wealth of colour in the soft October light. Eight o'clock " was striking at the church of Saint-Roch; not many people were about, only a few clerks on their way to business, and housewives doing their morning shopping. Before the door, two shopmen, mounted on a step-ladder, were hanging up some woollen goods, whilst in a window in the Rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin another young man, kneeling with his back to the pavement, was delicately plaiting a piece of blue silk. In the shop, where there were as yet no customer , there was a buzz as of a swarm of bees at work.

By Jove!" said Jean, "this beats Valognes. Your wasn't such a fine shop."

Denise shook her head. She had spent two years there, at Cornaillc's, the principal draper's in the town, and this shop encountered so suddenly - this, to her, enormous place, made her heart swell, and kept her excited, interested, and oblivious of everything else. the high plate-glass door, facing the Place Gaillon, reached the first storey, amidst a complication of ornaments covered with gilding. Two allegorical figures, representing two laughing, bare-breasted women, unrolled the scroll bearing the sign, " The Ladies' Paradise." The establishment extended along the Rue de la Michodiere and the Rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin, and comprised beside the corner house, four others - two on the right and two on the left, bought and fitted up recently. It seemed to her an endless extension, with its display on the ground floor, and the plate-glass windows, through which could be seen the whole length of the counters. Upstairs a young lady, dressed all in silk, was sharpening a pencil, while two others, beside her, were unfolding some velvet mantles.

Denise shook her head. She had spent two years there, at Cornaillc's, the principal draper's in the town, and this shop encountered so suddenly - this, to her, enormous place, made her heart swell, and kept her excited, interested, and oblivious of everything else. the high plate-glass door, facing the Place Gaillon, reached the first storey, amidst a complication of ornaments covered with gilding. Two allegorical figures, representing two laughing, bare-breasted women, unrolled the scroll bearing the sign, " The Ladies' Paradise." The establishment extended along the Rue de la Michodiere and the Rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin, and comprised beside the corner house, four others - two on the right and two on the left, bought and fitted up recently. It seemed to her an endless extension, with its display on the ground floor, and the plate-glass windows, through which could be seen the whole length of the counters. Upstairs a young lady, dressed all in silk, was sharpening a pencil, while two others, beside her, were unfolding some velvet mantles.

'The Ladies' Paradise," read Jean, with the tender laugh of a handsome youth who had already had an adventure with a woman. "That must draw the customers - eh?"

But Denise was absorbed by the display at the principal entrance. There she saw, in the open street, on the very pavement, a mountain of cheap goods-bargains, placed there to tempt the passers-by, and attract attention. Banging from above were pieces of woollen and cloth goods, merinoes, cheviots, and tweeds, floating like flags; the neutral, slate, navy-blue, and olive-green tints being relieved by the large white price-tickets. Close by, round the doorway, were hanging strips of fur, narrow bands for dress trimmings, fine Siberian squirrel-skin, spotless snowy swansdown, rabbit-skin imitation ermine and imitation sable. Below, on shelves and on tables, amidst a pile of remnant, appeared an immense quantity of hosiery almost given away; knitted woollen gloves, neckerchiefs, women's hoods, waistcoats, a winter show in all colours, striped, dyed, and variegated, with here and there a flaming patch of red. Denise saw some tartan at nine sous, some strips of American vison at a franc and some mittens at five sous. There appeared to be an immense clearance sale going on; the establishment seemed bursting with goods, blocking up the pavement with the surplus.

Uncle Baudu was forgotten. Pepe himself, clinging tigl1tly to his sister's hand, opened his big eyes in wonder. A vehicle coming up, forced them to quit the road-way, and they turned up the Rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin mechanically, following the shop windows .and stopping at each fresh display. At first they were captivated by a complicated arrangement: above, a number of umbrellas, laid obliquely, seemed to form a rustic roof; beneath these a quantity of silk stockings, hung on rods, showed the roundness of the calves, some covered with rosebuds, others of all colours, black open-worked, red w1th embroidered corners, and flesh colour, the silky grain of which made them look as soft as a fair woman's skin; and at the bottom of all, a symmetrical array of gloves, with their taper fingers and narrow palms, and that rigid virgin grace which characterises such feminine articles before they are worn. But the last window especially attracted their attention. It was an exhibition of silks, satins, and velvets, arranged so as to produce, by a skilful artistic arrangement of colours, the most delicious shades imaginable. At the top were the velvets, from a deep black to a milky white: lower down, the satins pink, blue, fading away into shades of a wondrous delicacy; still lower down were the silks, of all the colours of the rainbow, pieces set up in the form of shells, others folded as if round a pretty figure, arranged in a lifelike natural manner by the clever fingers of the window dressers. Between each motive, between each coloured phrase of the display ran a discreet accompaniment, a slight puffy ring of cream-coloured silk. At each end were piled up enormous bales of the silk of which the house had made a specialty, the ''Paris Paradise" and the "Golden Grain," two exceptional articles destined to work a revolution in that branch of commerce. "Oh, that silk at five francs twelve sous!" murmured Denise, astonished at the ''Paris Paradise."