Rosalind Williams, Dream Worlds

The Democratization of the Dream of Wealth

Desire for wealth is infinitely malleable. People have diverse ideas about how they would indulge themselves if they were rich, but their daydreams depend on the basic fantasy of possession of great wealth. With wealth other dreams can come true. In appealing to this fantasy, commerce can achieve a feat of reductionism and secure the broadest possible audience.

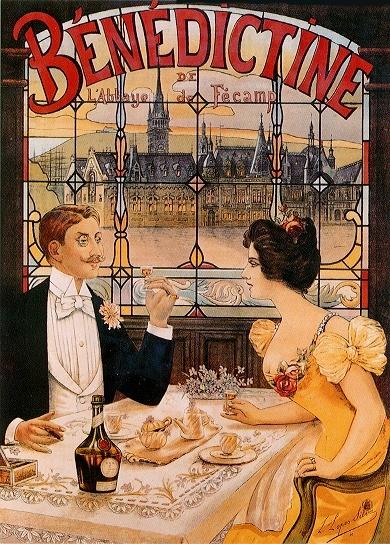

Environments of mass consumption are places where consumers can indulge temporarily in the fantasy of wealth. These environments are Versailles open to all, least during business hours. Without having to buy, the department-store shopper can handle and try on merchandise. For the relatively low price of admission, the exposition tourist can enjoy palaces and dancing girls, gaze on luxurious goods, travel in style, and otherwise taste pleasures normally reserved for the fortunate few. In the "picture palace," the moviegoer can be transported to high society to mingle with the rich. At the Salon de I'Automobile young couples can lounge in the crushed velvet seats of luxury vehicles before taking the Metro back home to cramped and drab apartments. Perhaps the consumer revolution intensified the pain of envy by bringing within the realm of possibility the acquisition of a degree of wealth that had formerly been considered out of reach. This point is stressed by Balzac, chronicler of that pain. But the consumer revolution also brought an anodyne in the form of environments of mass consumption, where envy is transformed into pleasure by producing a temporary but highly intense satisfaction of the dream of wealth.

The satisfaction of this dream on a less intense but more lasting basis was another long-term accomplishment of the consumer revolution. The outpouring of new commodities in the late nineteenth century created a world where a consumer could possess images of wealth without actually having a large income. This magic was wrought, in the first place, through the alchemy of scientific and technological advances that permitted hitherto expensive articles to be made much more cheaply or to be imitated convincingly and inexpensively. The other major advance making possible a widespread illusion of wealth was the vast expansion of credit. As we have seen, courtiers had customarily bought their luxuries with borrowed money; at the other end of the social scale, the poor had long purchased food on credit. During the consumer revolution the habit of borrowing permeated the ranks of the bourgeoisie, and credit buying began to be used for a wide range of consumer goods. Credit became a branch of big business. French retailers of food, drink, and pharmaceuticals had long offered credit (and had tradition ally been expensive in consequence), but they did so on a personal, unsystematic, unwritten basis. During the consumer revolution borrowing was transformed into a largescale, impersonal, rationalized system of installment purchase which made possible the acquisition of goods with out ready cash- indeed a fantasy come true.

Installment plans were "developed into a national institution" in France by Georges Dufayel (1855-1916), beginning in the 1870s. His clients generally paid 20 percent of the standard purchase price for household goods at over 400 stores accepting Dufayel's tokens, and repaid the rest in small weekly installments. Dufayel received 18 percent commission on his sales. By the turn of the century the Dufayel firm had served over three million customers and had branches in every large French town . In Paris alone 3,000 clerks were employed to handle the orders and another 800 went out each day to collect repayments.

These figures, however, do not fully convey the significance of credit purchase in allowing an ordinary wage earner to enjoy a convincing illusion of wealth. The power of that illusion is expressed more vividly in the magnificent store, costing $10,000,000, that Dufayel built in the Rue de Clignancourt just after the turn of the century. "On entering Dufayel's store by the principal door," remarked one admiring observer, "it seems as though you are entering a palace rather than a shop." The entrance porch was richly ornamented with carvings and statues representing themes like "Credit" and "Publicity" and surmounted by a dome 180 feet high. Inside the building were 200 statues, 180 paintings, pillars, decorative panels, bronze allegorical figures holding candelabras, painted ceramics and glass, and grand staircases, as well as a theatre seating 3000 that was decorated with silk curtains, white-and-gold foliage wreaths, and immense mirrors. But Dufayel's establishment was more than a reproduction of a palace of the ancien régime: it also incorporated the most up-to-date attractions of consumer society. If there was a traditional cut-glass chandelier inside the dome, on the outside, at the very top, was a revolving light of ten million candlepower (almost as powerful as the searchlight on top of the Eiffel Tower) visible for twelve miles "which makes an excellent advertisement at night." If the theatre was "an object of astonishment and admiration to all visitors," who attended monthly musical performances there, the far plainer Cinematograph Hall in the basement was far more popular. There 1,500 people paid admission to attend each of four hour-long performances every day. "The cinematograph attracts many people to the store, and is an ingenious and profitable method of advertising." Dufayel's genius was to transform the traditional decor of an aristocratic palace into a modern, democratic environment of mass consumption.29 The decor of the building faithfully symbolized its merchandise: to sell credit was to sell the illusion of princely wealth to the masses. Dufayel's firm was so successful that rival credit companies were established, and department stores, beginning with the Samaritaine in 1913, began to organize their own credit companies.30 The proliferation of credit, together with the proliferation of inexpensive imitation goods, permitted (in a phrase then popular) "the democratization of luxury." As the word democratization suggests, the dream of wealth, more than any other dream yet mentioned, has a social dimension, and it is therefore worthy of special attention.