Excerpts from the Journal of Edmond de Goncourt

Friday, November 11

The wounded man is in favor. As I go along the Boulevard Montmorency, I see a lady taking a wounded in grey overcoat and police cap for a ride in her open carnage. She has eyes only for him; she continually adjusts the fur laprobe; the hands of mother and wife are constantly running over his body

her open carnage. She has eyes only for him; she continually adjusts the fur laprobe; the hands of mother and wife are constantly running over his body

The wounded man has become fashionable. For others he is an object of utility, a lightning rod. He defends your dwelling from invasion by the suburban population; he will save you later on from fire, pillage, and Prussian requisition. Someone was telling me that one of his acquaintances had set up a hospital in hi's house. Eight beds, two nursing sisters, lint, bandages, nothing was lacking. But no wounded man in sight. The householder was full of anxiety about his house. What did he do? He went to a hospital where there were lots of wounded men and paid three thousand francs, yes, three thousand francs, to have one of them turned over to him.

I deeply wish for peace; I very selfishly hope that no shells will fall on my house and my treasures. However, I was walking sad as death the full length of the fortifications. I vas looking at all those works which will not protect us against German victory. I felt from the attitude of the workmen, the National Guards, and the soldiers, from what people around me were admitting to each other, that peace was signed in advance and on M. de Bismarck's terms. And I suffered stupidly as from a disappointment, a disillusionment about one I loved. Someone was saying to me this evening: "The National Guards! Let's not talk about them. The infantry will raise their rifles in the air; the Mobiles will hold out for a little while; the sailors will fire without conviction. That's how they will fight, if they do fight."

Saturday, November 12

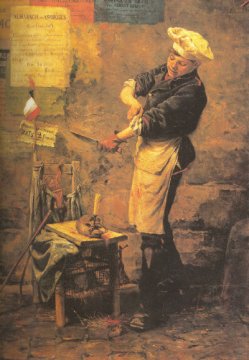

Let posterity beware of telling future generations about the heroism of the Parisians in 187o. Their heroism will have consisted solely in eating strong butter on their beans and serving horse meat instead of beef-without being too much aware of it, since the Parisian has little discrimination about what he eats.

Sunday, November 13

In the midst of everything that straitens and menaces life at this moment, there is one thing that sustains it and stirs it up, almost makes you love it: emotion. To go beneath the cannon fire, to risk your life at the foot of the Bois de Boulogne, to see flames leaping out of the houses at Saint Cloud as they are today, to live under the constant emotion of a war which surrounds you and almost touches you, to rub elbows with danger, always to have your heart beating fast: that has its sweetness, and I feel that, when this is all over, hectic enjoyment will be followed by dull boredom, very dull, very dull.

This evening in the resonance of a frosty night you can hear constantly repeated all along the ramparts in a striking chant: "Sentinels, on guard," accompanied by the continuous sound of distant cannons, which arc like bursts and cracklings of lightning in the mountains.

Tuesday, December 6

Tuesday, December 6

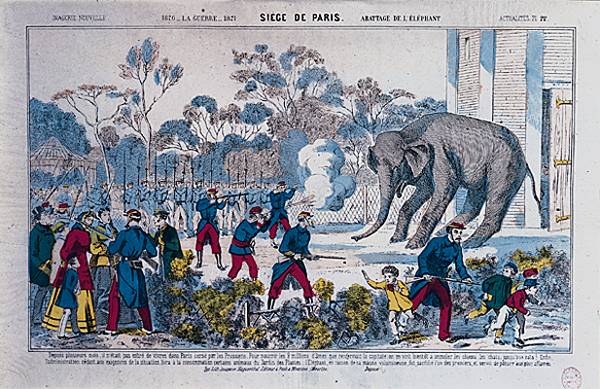

On today's bill of fare in the restaurants we have authentic buffalo, antelope, and kangaroo.

In the open air this evening under any light, under any improvised street light, consternation-struck faces bend over squares of newspaper. It is the news of the defeat of the Army of the Loire and the recapture of Orleans.

Thursday, December 8

You talk only about what is eaten, can be eaten, or can be found to eat. Conversation does not go beyond that.

"You know, a fresh egg costs twenty-five sous!"

"I hear there is an individual who is buying up all the candles in Paris, and out of them, by adding a little color, he makes that grease which is so expensive."

"Oh, keep away from cocoa butter; it stinks up the house

for at least three days."

"I saw some dog cutlets; they're really very appetizing: they look just like mutton chops."

"Now tell me, who has eaten kangaroo?"

"Let me tell you about something good! You cook some macaroni and put it in a salad with plenty of greens. What more can you ask for in these times!"

"Don't forget. There are still some canned tomatoes at Corcelet's.''

Hunger is beginning and famine is on the horizon. Elegant Parisian women are beginning to turn their dressing rooms into henhouses. You figure, you count, and you wonder whether even by using all the waste, all the scrapings, all the parings, there will be anything left to eat in two weeks.

We .shall lack not only food, but also light. Oil for lamps is becoming scarce, candles are at an end. Worse than that, with the cold weather we are having we are getting close to the time when we will be without coal, or coke, or wood. Then

we shall endure famine, cold, and darkness; the future seems

to hold sufferings and horrors such as have not been experienced in any other siege.

Saturday, December 10

Nothing more unnerving than this state in which hope stupidly tries to believe for a moment all the untruths, the lies, the nonverities of journalism, then falls back immediately into doubt and unbelief about everything. Nothing more painful than this state in which you don't know whether the provincial armies are at Corbeil or at Bordeaux, or whether those armies even exist any more. Nothing more cruel than to live in darkness, in night, in ignorance of the tragic fate which threatens, surrounds, and stifles you. It really seems as though M. de Bismarck has shut up all Paris incommunicado in a prison cell.

For the first time I see people in line at the dry-grocers'disturbing lines of people pouncing indiscriminately on all the canned goods that are left in these shops.

In the streets, collections on behalf of the wounded cross convoys of the dead; and big calico alms bags, looking like those you see in Italy at carnival time, are carried even to the second floor to solicit charity from the people at the windows.

These days there is nothing more provincial than one of the big Paris cafes. How is that? Perhaps because of the scarcity of waiters, because of the endless reading of the same newspaper, because of the crowds that form in the middle of the cafe to talk about the things they know, as people talk about local things in a small city, or indeed because of a stupefied habituation to the place, where in former days, distracted only by light thoughts and eager for the pleasures and thousand distractions of Paris, people paused only for a moment, with the lightness of birds of passage.

Everybody is losing weight; everybody is getting thin. You are always hearing of men who have to have their trousers taken in: Theo laments that he has to wear suspenders for the first time, since his belly won't hold up his pants.

Friday, December 16

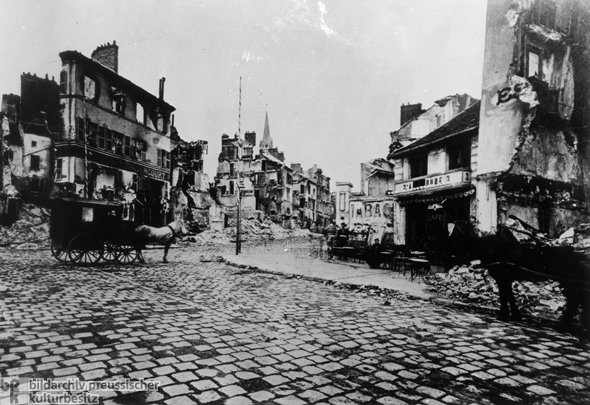

Today the official news of the fall of Rouen. I am happy in my confidence that Flaubert's threat to blow out his brains

was nothing but hyperbole. .

To be overcome by a stupid love for my shrubbery, passing hours trimming the old ivy of its dead stalks, cultivating my violet plants, mixing up earth and fertilizer for them -- all this while the Krupp cannons threaten to make a ruin of my house and garden; it's too stupid! Grief has turned me into animal, has given me the manias of an old shopkeeper in retirement. I am afraid that under my man-of-letters skin there s nothing left but a gardener.

Sunday, December 25

It is Christmas. I hear a soldier say: "By way of celebration we had five men frozen in our tent."

What a remarkable transformation of business and what a bizarre transformation of shops! A jeweler on the Rue de Clichy now shows eggs wrapped in cotton wool in his jewel boxes. In the part of the window usually given over to silver, you see chickens, ducks, jellied meat; and a big sign announces: Roast Goose by the Piece.

Right now the mortality is very high in Paris. It is not absolutely the result of hunger, and the deaths are not confined to the sick and sickly--who are finished off by the restricted diet and present hardships. Much of this mortality comes from grief, displacement, homesickness for the sunny corners in the Paris region from which these refugees came. Of the tiny migration from Croissy-Beaubourg--twenty-five people at most-five are already dead.

Friday, December 30

Truly, France is accursed! Everything goes against us. If the cold and bombardment continue, there will be no water with which to put out the fires, All the water in the house is frozen, practically up to the chimney cornerTuesday, January 1o

The gunfire this morning is so rapid that it seems as regular as a steam-engine piston.

As I ride into Paris with a sailor from the Point du Jour battery, he tells me that yesterday there was such a hail of shells that they had to endure seventeen salvos lying on the ground without being able to return the fire. After that they fired a whole battery and blew up an ammunition dump. In spite of the terrible fire they so far have had only three wounded: one with his thigh severed who died, another seriously wounded, and a seaman who had his eyes and beard burned when a shell burst in front of his face.

There are a good many of us at Brebant's this evening. Everybody who has been under bombardment wants to hear what as happened to other people. Charles Edmond gives a fantastic description of the bombs that rained on the Luxembourg. Because shell fell in the Place Saint Sulpice, SaintVictor deserts his lodgings on the Rue Furstenberg at night. Renan has emigrated to the Right Bank.

Wednesday, ]anuary 18

Today the ration is 400 grams per person. Imagine that there are people condemned to live on so little! Women were weeping in the line at the  Auteuil bakery.

Auteuil bakery.

Now it is not just a few stray shells as on previous days but a hail of lead, which bit by bit surrounds and hems us in. All around me explosions which burst fifty, ninety-five feet away: at the railroad station, on the Rue Poussin, where a woman's foot was blown off, in the house next door which had already had its first experience day before yesterday. And while I am at the window picking out the Meudon batteries with my glasses, a shell fragment almost hits me and spatters mud against the door of my house. . . .

Friday, January 20

Trochu's dispatch last night seems to me to be the beginning of the end; it poisons my stomach. . . .

In Paris, on the boulevard, I encounter anew the despairing discouragement of a great nation which has done much to save itself by its Own efforts, its resignation, its morale, and feels that it has been lost by military stupidity.

I have dinner at Peters' next to three of Franchetti's scouts. Theirs is absolute despair under the mask of irony, the special form that·French despair takes: ''We've had it, we've had it!" They speak of the Army of Paris which is unwilling to fight any longer, of the heroic core which kept it together killed at Champigny and at Montretout, and always, always, they speak of their leaders' incapacity. .

It is odd that in the situation I am in, in the grief that devours me, I still have a cowardly desire to live, and on the way home I seek to avoid the shell whistling by me which might bring me deliverance!

Saturday, January 21

I am struck more than ever by the silence, the silence of

death, which disaster brings in a great city. Today you can no longer hear Paris live.

Every face is that of a sick man or a convalescent. You seeonly thin, drawn, pale faces; you see only yellowy pallor like horse fat.

In front of the me on the omnibus are women in full mourning: mother and daughter. The black-gloved hands of the mother are constantly twisting and moving mechanically to her red eyes, which are unable to weep any more, while a tear, slow of fall, dries from time to time at the edge of the daughter's eyes, which are raised to heaven.

On the Place de la Concorde near the tattered flags and withered immortelles on the Strasbourg statue a company is encamped, blackening the walls of the Tuilleries garden with their fires, their heavy knapsacks making a sort of shield for the balustrade. As you go among them you hear words like these: "Yce, our poor little adjutant is being buried tomorrow."

I go up to the Luxembourg Palace, to Julie's house; she reads me a letter from her son-in-law saying that in the Montretout battle he had to drive the fleeing National Guards and Mobiles back with a stick.

We have seen the pork-butcher shops become empty places one by one, decorated only by yellow pottery and aucuba plants with leaves veined like white marble; the butcher shops have drawn curtains behind padlocked grilles. Today it is the bakery shops' turn, and they have become dark holes with hermetically sealed show windows.

Burty had it from Rocheforte that when Chanzy saw his troops flee, he charged them sword in hand; then, seeing that blows and abuse were of no use, he ordered the artillery to fire on them.

A curious and very symptomatic phrase: A girl whose heels clip-clop behind me on the Rue Saint Nicholas says to me: "Sir, will you come up to my room in return for a piece of bread?" ,