Colin Jones, Paris: A History

Haussmannization in the Context of the History of Paris

What perhaps most marks out what contemporaries were already beginning to call Haussmannization from the processes of urban development which preceded it was the unitary, holistic vision which underpinned it - even if that unitary vision was the work of two men. Few of the elements in this vision were new. After all, the city had been used as a dynastic power site since the Romans. The straight urban street had been highly valued during the Renaissance. Boulevards had existed since the time of Louis XIV. There had been moves to extend the city's perimeters by royal edict under Louis XVI. Napoleon I had attended to the city's infrastructure and sought to highlight prestigious monuments within the cityscape. Furthermore, much of the detail of urban renewal which would be associated with the notion of Haussmannism had already been trialled by Prefects Chabrol and Rambuteau. The latter in particular had devised the method of renovating decaying neighbourhoods by creating new streets.

Nonetheless, it was under the Second Empire that these existing features of urban transformation were fused together into a programme of urban renewal covering all the functions which the city performed. Whereas Rambuteau and Chabrol had eschewed the idea of any plan d'ensemble [overall plan for the entire city], Haussmann and Napoleon III gloried in it. For them the modern city was an organism which needed to be analysed according to a strictly utilitarian examination of urban functions. Napoleon and Haussmann saw themselves as physician urbanists, whose task was to ensure Paris's nourishment, to regulate and to speed up circulation in its arteries (namely, its streets}, to give it more powerful lungs so as to let it breathe (notably, through green spaces), and to ensure that its waste products were hygienically and effectively disposed of. These were all aspects of the new Paris which Napoleon proudly showed off to the world at the international Expositions which he held in the city in 1855 and 1867. The world was duly dazzled.

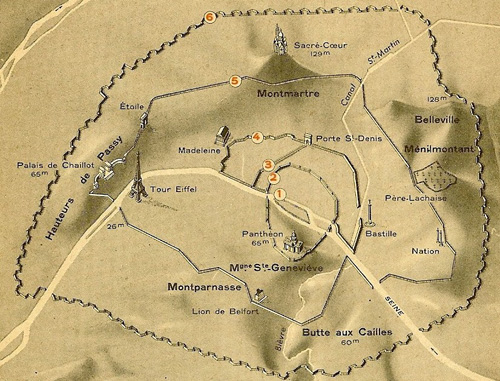

The Succession of Walls around Paris from the Middle Ages Until the 19th Century

The Rue de Rivoli was opened by Napoleon I in 1802 from the Place de la Concorde to the Lourvre and served as a model for the later development of the city

In the past Paris had often been viewed as a great city whose grandeur could be registered in the vestiges that the past had left on its face. This equation between greatness and the monumental record had already been eroded during the eighteenth century under the pressure of more utilitarian approaches. Although Napoleon Ill accentuated his regime's links to both Roman and Napoleonic empires, Paris's own history played very little part in his vision for the city. Similarly, although Napoleon referred to his projects as 'embellishments', Haussmann himself admitted he thought essentially in terms of Paris's security, circulation and salubrity'. Neither man displayed much nostalgic or aesthetic appreciation of the lived environment of the old city. Haussmann, it is true, employed photographers such as Charles Marville and watercolourists like Davioud to make 'before-and-after' pictures of areas being transformed by his works -- but the emphasis was less on nostalgia for a world that was being lost than relief at its being consigned to history.

History was notable only by its absence from the list of core features of the programme of Haussmannization which Napoleon highlighted to the municipal council in 1858. His vision was of major arteries opening, populous areas becoming healthier, rents tending to gey lower as a result of mo re and more building, the working class getting richer through work, poverty diminishing through better organization of relief, and Paris responding to its highest calling.

The 'highest calling which Napoleon III, in this vaguely messianic way, planned for Paris was the metamorphosis of an ailing city into the capital of the world , the shining light of the modern age. Like all such missions, the project of renewal stressed how bad the state of Paris had been prior to its own advent. The political economist Victor Considerant vehemently described Paris in 1848 as 'a great manufactory of putrefaction in which poverty, plague ... and disease labour in concert and where sunlight barely ever enters. [It i s] a foul hole where plants wilt and perish and four out of seven children die within their first year. 'Paris, in its state following the 1848 Revolution,' the writer Maxime du Camp later agreed, was on the point of becoming uninhabitable. Its population [was] suffocating in the tiny, narrow, putrid, and tangled streets in which it had been dumped . As a result of this state of affairs, everything suffered: hygiene, security, speed of communications and public morality.

To some degree these damning verdicts on the condition of mid-century Paris are exaggerations which accentuated the Second Empire's achievement. Paris at mid-century obviously faced many major social problems. Yet, despite the doom-sayers, it was still the largest manufacturing city in the world, was a major financial centre, had a young and dynamic workforce, had put in place a railway infrastructure and was beginning the work of reinventing itself as a modern city. The criticisms of pre-Haussmann Paris did , however, contain an important nugget of truth: namely, that by mid-century the city was widely perceived as a dangerous, unhealthy and frustratingly difficult place to inhabit. This meant that there was a groundswell of desire from within the urban community for a more liveable city. This does not mean to say that if Haussmann had not existed, the Parisians would have invented him. But it does signify that Haussmannism was already in the air.