David W. Galenson and Robert Jensen, Careers and Canvases: The Rise of the Market for Modern

Art in the Nineteenth Century

The economists David Galenson and Robert Jensen had certain objections to some of the arguments presented more than forty years earlier in Harrison C. and Cynthia A. White's influential Canvases and Careers, but their general summary of the earlier arguments provides a good introduction to the changes that the Parisian art market was undergoing in the second half of the 19th century.

Canvases and Careers describes a change in what the authors refer to as the institutional structure of the 19th-century French art world, from what they call the Academic system to the dealer-critic system. This section briefly summarizes the authors’ account of these two regimes.

The Academic system was controlled by the government’s Académie de Peinture et Sculpture (hereafter the Academy). Aspiring artists were educated at the government’s Ecole des Beaux-Arts, where they were taught to use traditional methods to emulate the work of their teachers. While at the Ecole students advanced if they passed annual examinations, and participated in a series of contests designed to identify the most talented. After graduation, the goal of young artists was to display their paintings at the Salon, the great annual or biennial exhibition that was the French art world’s principal showcase for new work. Admission to the Salon was regulated by a jury. Although its composition varied, a majority of the jury’s members were usually associated with the Academy. The Academy consequently used the Salon as a continuing means of control over artists: not only acceptance of their paintings, but preferential placement of their work in the many crowded halls of the Salon, and access to the medals that the jury awarded to recognize distinction, were all central to building the reputations that would create a demand from private clients for the artists’ work.

The Whites argue that the Academic system focused not on artists’ careers but on the individual canvases shown at the Salon: “By the system’s own definition ... each canvas led an independent existence as a separate entity with its own reputation and history ... It was the picture, not the artist, around which the official ideology centered ...

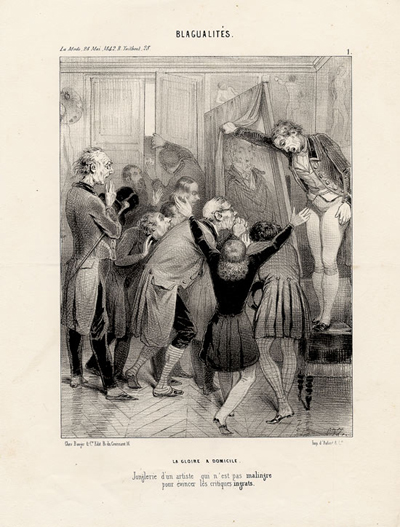

Dauumier, The Triumphal March (1855)

[An artist on his way to submit his work to the Salon jury.]

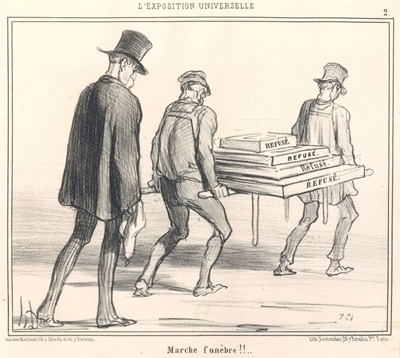

Daumier, Funeral March (1855)

[An artist returning from the Salon Jury, his works having been rejected.]

The Academic system emphasized individual canvases rather than the careers of painters.”2 They contend that this became an increasingly damaging flaw as the number of French artists grew over the course of the century, and the Salon was overwhelmed by massive numbers of unrelated works. Thus what undermined the power of the Salon was not any small group, but rather growing masses of aspiring painters: “Pressure from the greatly expanded number of professional painters on an organizational and economic framework conceived to handle a few hundred men was the driving force toward institutional change.”3 After mid-century, the Academic system progressively gave way to a new system.

The new system was initiated by the Impressionists: “The Impressionists seemed to mark a basic new era in art primarily because they ushered in a new structure for the art world. Let us call this new institutional system the dealer-and-critic system.”4 The new system emerged partly in response to a growing demand for paintings by members of the French middle class. Instead of the large paintings of historical subjects favored by the Academy, which had typically been purchased for public museums and stately mansions, the new buyers wanted smaller paintings of less formal themes to decorate their homes. Private dealers emerged to serve these customers.

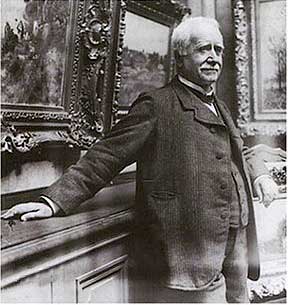

The Whites cite a listing that identified no less than 104 art dealers in Paris in 1861.5 These dealers created a new system that focused not on individual paintings, but on the careers of artists. Because a dealer would establish a continuing business relationship with an artist, the dealer had an interest in building the artist’s reputation, in order to create a consistent demand for his work: “A current painting as an isolated item in trade is simply too fugitive to focus a publicity system upon ... [I]t was the career of an artist that had to be the focus of the system.”6 Critics also assumed a new importance in this system. Instead of merely judging the works presented to the public at the Salon, their writing could serve as an alternative means of publicizing artists’ work. And as the early development of modern art began to shift the interest of artwork from subject matter to technique, critics began to play a more complex role as theorists for new developments. Yet as their primacy in the Whites’ name for the new system suggests, dealers were the primary force in creating and developing the new system. The pioneers were the dealers Durand-Ruel, father and son: “The elder Durand, beginning in the 1820s as a merchant of artists’ paper, canvas, and colors ... became the exclusive dealer in works of the then ‘modern’ school. Constable, Delacroix, and the Barbizon landscapists were his first ‘collection.’”7 Paul Durand-Ruel took over the gallery after his father's death in 1865: “Durand the younger began an aggressive program to create and maintain a bullish market. He bought up large numbers of works by the ‘School of 1830.’...His ‘campaign in favor of those called Impressionists’ began in 1870, when he met Monet and Pissarro in London ... [H]e would make substantial advances to the painters, to be paid off in pictures... The Impressionist’s [sic] dealer, in effect, had recreated the role of patron -- in the Renaissance sense of the word... [T]he support artists received from him was a close approximation of the patronage relationship of earlier times ... Thus, as speculator and patron, he set a pattern that was soon adopted by other contemporary dealers.”8

With dealers serving as the entrepreneurs, and critics as the publicists and theoreticians for the new art, the dealer-critic system replaced the Academic system: “The Academy and the state were once arbiters of taste, patrons, educators of the young, and publicists. Now these functions were spread out and assumed by different parts of the new system.”9 Competition, in both economic and intellectual markets, was the hallmark of the new system: “dealer-patrons were in competition with one another and each critic was eager to be spokesman for his own artistic movement.”10 The free market thus became the artist’s protector, as “this framework provided more widely and generously for a larger number of artists and particularly for the young untried painter than did the Academic arrangements.”11

The dealer-critic system developed over the course of the second half of the century. It benefited the Impressionists only late in their careers, “for they came along before the new system was fully developed and legitimate.”12 But the leaders of the next generation were in a different position: “Gauguin, Signac, and Seurat had been nurtured in the Impressionists’ world of café discussions, joint learning and experimentation, group exhibition and dealer competition.”13

Art Dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922)