Gustav Courbet, "Art Cannot Be Taught"

In 1861 a group of students, who were dissatisfied with the Ecole des Beaux Arts, asked painter Gustave Courbet to teach them the theory and the practice of Realism. He accepted them with the provisos that there would be equality himself and the younger artists and that each student would develop his own perspective on contemporary reality. Courbet put his ideas about becoming an artist in the following letter. It provides striking contrast with the conservative attitudes toward art and the artist that we encountered yesterday and indicate the direction that art would move in the decades ahead.

PARIS, DECEMBER 25, 1861

GENTLEMEN AND COLLEAGUES:

You were anxious to open a studio of painting where you would be able to continue your education as artists without restraint, and you were eager to suggest that it be placed under my direction.

Before making any reply, I have to get things straight with you about that word direction. I can't lay myself open to making it a question of teacher and students between us.

I must explain to you what I recently had the occasion to tell the congress at Antwerp: I do not have, I cannot have, pupils.

I, who believe that every artist should be his own teacher, cannot dream of setting myself up as a professor.

I cannot teach my art, nor the art of any school whatever, since I deny that art can be taught, or, in other words, I maintain that art is completely individual, and is, for each artist, nothing but the talent issuing from his own inspiration and his own studies of tradition.

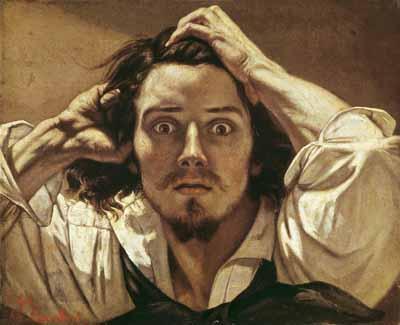

Gustave Courbet, Self-portrait (The Desperate Man), c. 1843–1845

Gustave Courbet, The Painter's Studio; A Real Allegory [Detail] (1855)

I say in addition that, in my opinion, for an artist art or talent can only be a way of applying his own personal abilities to the ideas and objects of the time in which he lives.

Above all, the art of painting can only consist of the representation of objects which are visible and tangible for the artist. An epoch can only be reproduced by its own artists, I mean by the artists who lived in it. I hold the artists of one century basically incapable of reproducing the aspect of a past or future century-in other words, of painting the past or the future.

It is in this sense that I deny the possibility of historical art applied to the past. Historical art is by nature contemporary. Each epoch must have its artists who express it and reproduce it for the future. An age which has not been capable of expressing itself through its own artists has no right to be represented by subsequent artists. This would be a falsification of history.

The history of an era is finished with that era itself and with those of its representatives who have expressed it. It is not the task of modern times to add anything to the expression of former times, to ennoble or embellish the past. What has been, has been. The human spirit must al ways begin work afresh in the present, starting off from acquired results. One must never start out from foregone conclusions, proceeding from synthesis to synthesis, from conclusion to conclusion.

The real artists are those who pick up their age exactly at the point to which it has been carried by preceding times. To go backward is to do nothing; it is pure loss; it means that one has neither understood nor profited by the lessons of the past. This explains why the archaic schools of all kinds are brought down to the most barren compilations.

I maintain, in addition, that painting is an essentially concrete art and can only consist of the representation of real and existing things. It is a completely physical language, the words of which consist of all visible objects; an object which is abstract, not visible, non-existent, is not within the realm of painting.

Imagination in art consists in knowing how to find the most complete expression of an existing thing, but never in inventing or creating that thing itself.

The beautiful exists in nature and may be encountered in the midst of reality under the most diverse aspects. As soon as it is found there, it belongs to art, or rather, to the artist who knows how to see it there. As soon as beauty is real and visible, it has its artistic expression from these very qualities. Artifice has no right to amplify this expression; by meddling with it, one only runs the risk of perverting and, consequently, of weakening it. The beauty provided by nature is superior to all the conventions of the artist.

Beauty, like truth, is a thing which is relative to the time in which one lives and to the individual capable of understanding it. The expression of the beautiful bears a precise relation to the power of perception acquired by the artist.

Here are my basic ideas about art. With such ideas, to think of the possibility of opening a school for the teaching of conventional principles would be going back to the incomplete, received notions which have everywhere directed modern art up to this point. ...

It is not possible to have schools for painting; there are only painters. Schools have no use except for discerning the analytic procedures of art. No school is capable of pressing on to a synthesis in isolation. Painting cannot, without falling into abstraction, let a partial aspect of art dominate, whether it be drawing, color, composition, or any other one of the extraordinary multiplicity of means the totality of which alone consti tutes this art.

I am, therefore, unable to open a school, to form pupils, to teach this or that partial tradition of art.

I can only explain to some artists, who would be my collaborators and not my pupils, the method by which, in my opinion, one becomes a painter, by which I myself have tried to become one since my earliest days, leaving to each person the complete control of his individuality, the full liberty of his own expression in the application of this method. To achieve this aim, the organization of a communal studio, recalling those extremely fruitful collaborations of the studios of the Renaissance, could certainly be useful and contribute to the opening of the era of modern painting, and I would eagerly give myself to everything you want of me in order to attain this goal.

With deepest sincerity.

GUSTAVE COURBET

Gustave Courbet, The Cellist, Self Portrait (1847)