A Glut in Search of a Market

Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), pp.83-84, 88-89.

At least 200,000 reputable canvases must have been produced in each decade after midcentury by professional

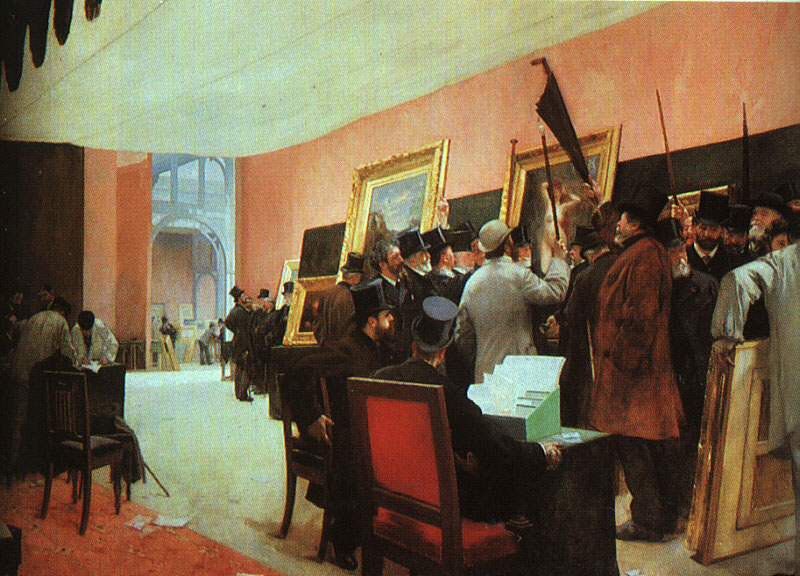

Henri Gervex, The Jury for Painting Salon des Artists (1885) |

French painters. This is the single dominant fact in our account, an index of the problems confronting the Academic system. Our minimum estimates derived earlier are (around 1863) 3000 recognized male painters in the Parisian system and another 1000 men in provincial orbits. We omit consideration of women painters, occasional painters, and professional artists in other fields who did some painting. Major painters, we know from detailed oeuvre catalogues, often turned out fifty or more salable oil paintings in a year. More often than not, the typical painter entered two or three pictures in a given Salon, and these were usually but a selection of his most promising works on hand.

The days of "les grandes machines,' the enormous neoclassical painting or the panoramic battle scene, were numbered. As early as 1837 the reviewer for Le Moniteur Universel noted their scarcity, commenting that there was no longer room to hang them. This was an element: a painter had a better chance of being accepted with small pictures which were not such a problem to display. The greatest influence, however, was the demand for small genre painting and landscape, an increasing trend with buyers. A painter finished many of these in the year it would have taken him to complete one large work.

CANVASES VS CAREERS

Four thousand is not a staggering number of professionals to encompass in a decentralized institutional system. But in this case 3000 men were in one lump, in the core of the Academic institutional system centered on Paris, and few leaders of this system recognized a responsibility to organize and support such a large group. The other major difficulty was that the focus of the Academic system was not men, not a set of careers, but rather the river of canvases. By the system's own definition, moreover, each canvas led an independent existence as a separate entity with its own reputation and history. Yet the system never developed, within its own confines, the capacity to place this hoard of unique objects for pay. Not all paintings had to be placed, of course, nor were they placed by the alternative system of dealers and critics that was evolving. But enough of them had to be placed to give the artist some semblance of the regular income necessitated by his own middle-class view of himself. It was a view derived, in many cases, from his own family background and enforced by the official ideology of the Academic system, an ideology of the respectability of the artist as a learned professional.

It was the picture, not the artist, around which the official ideology centered. A certain static grandeur was associated with each individual work. The figure of the artist had an analogous static quality. The Academic aim had been to place him in the empyrean, a grand figure of learning.

It is exceedingly difficult to evaluate and process a large number of objects, using a single centralized organization, when the objects are defined as being unique. Fatigue bore upon the jury of the single yearly Salon, as they stumbled, almost unseeing, amid the thousands of paintings submitted. At these times, reality compelled attention to artists as individuals in a social context; thus for some of the jury log-rolling of the crassest kind dominated their deliberations, rather than concern with the type and quality of each painting.