Realities of Training

Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), p.26.

As you read this description of the ways that an increase in the number of artists strained the Academy's system, think about how these changes might have resulted in mnore freedom for innovation in the arts.

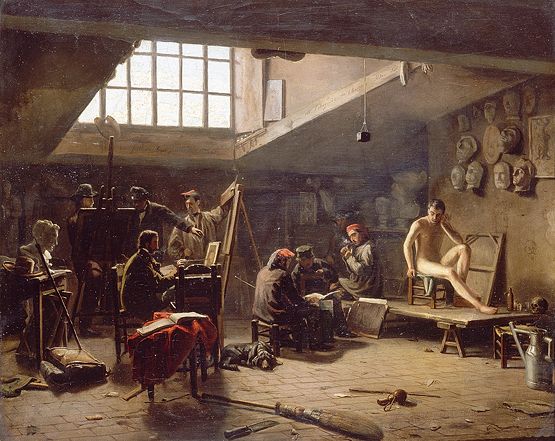

For the bulk of aspiring artists the system of training was by no means smooth and tightly knit. As the flow of students increased during the nineteeth century, the Ecole and associated ateliers had to adapt to numbers larger than they had been conceived to handle. The rote copying method of teaching, the mainstay of a beginner's training in the Ecole, could easily be extended to large classes, as could the atelier system where the master appeared once a week. But the larger the class, the less individual attention and the less thorough the indoctrination. Teaching at the Ecole was under constant fire from all sides; the liberals claimed it stifled creativity with its dull, exact reproductions of an infinitude of plaster casts; the conservatives claimed that it had degenerated into an undisciplined, superficial training which produced, at best, facile copyists and no artists "in the great tradition of French painting."

New informal "schools" sprang up to take advantage of the growing numbers. For those who failed the entrance exam at the Ecole or did not have the money to enter a private atelier, there were the "free" academies which provided nothing but a studio and a model, where anyone might pay the small model fee and drop in to work a while. The Academie Suisse, run by a former model, and the Academie julien, whose proprietor took a personal interest in "students" like Gauguin, were the two best known.

Thus official supervision became more and more cursory for the bulk of the students and alternatives to official training appeared. The twin results were half-trained artists and undamped sparks of novelty in the better students: Courbet serves as perhaps the most vivid example.