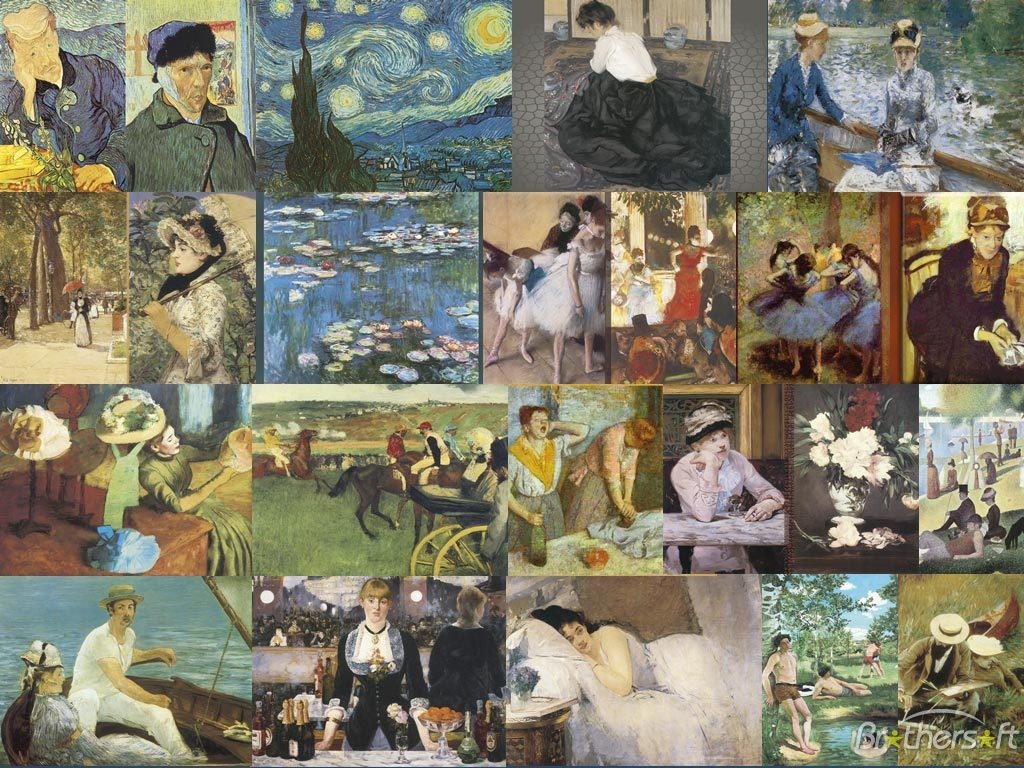

The Impressionists: Their Role in the New System

Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), pp.111-

IT is by tracing the success of the Impressionists that one can best discern the emergence of a new institutional system. They were contributors to a new conception of the artist. Yet their ambitions, their attitudes, and their careers were as much the products of the Academic system as they were the results of innovation and rebellion.

Only slowly were the Impressionists forced to think of themselves as rebels. It was only under the severest external pressure, cognitive and material, that the individual painters acted, much less thought, like a group -- and even then with endemic backsliding and bickering. The name "Impressionist" was in the great tradition of rebel names. Thrown at them initially as a gibe to provide a convenient handle to insult them, it was adopted by the group in defiance and for want of a better term and made into a winning pennant.

Sympathetic critics like Zola lumped the Impressionists together as a distinct group just as did the negative critics. To men versed in the lore of literary and political rebel groups, it was natural to do so. And how much easier and more entertaining it was than trying to follow the now outmoded academic hierarchical categories, which grouped paintings by subject matter. It is true stylistic labels were common earlier (as in "Colorists," "Linearists," "Romanticists," "Realists"); but never had they been attached so specifically to a small group of men with such implications of their being a definite social entity.

Independent exhibitions and the publicity they brought were at first thought of only as a means for getting known. Independent recognition, the Impressionists were sure, would eventually allow them to force their way into the Salon and official acclaim. They accepted the new system of independent and dealer exhibition as more than a temporary expedient only when the Salon had lost its legitimacy and become just another show. In 1881 the Salon passed from Academic-governmental control into the hands of the newly formed Society of French Artists. From that time on, independent groups and exhibitions multiplied rapidly.

The Impressionists were, as we shall see, middle-class men with

middle-class aspirations. They could not and did not fit into the Bohemian, avant-garde role of romantic legend. In style of life and attitudes toward their profession they adhered to the ideology created by the Academic system in its two centuries of rule. Yet the pressures created by that rule altered working habits of the Impressionists, changed their means for attaining the goals set by Academic ideology, and allowed the new system eventually to claim them as proteges. In this process, a changed concept of the artist came about, and simultaneously a clearer specialization of roles in the art world.