Zola, “Naturalism in the Salon” (1880)

These last few years something very interesting and instructive has been happening under our own eyes. I refer to the independent exhibitions put on by a group of painters that have been called "the Impressionists." . . . I use this term "Impressionist" here, because a label is really wanting to name the young artists who, in the wake of Courbet and of our great landscape painters, have devoted themselves to the study of nature. . . . When we come down to it, as a working painter Courbet himself is a magnificent classic. . . . the true revolutionaries of form appear with Mr. Edouard Manet, with the Impressionists, Messrs. Claude Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Guillaumin, and still others. These propose to get out of the studio in which painters have shut themselves up for so many centuries, and go paint in the open. In the open, the light is no longer uniform, and this means a multiplicity of impressions. [ . . . ] This study of light in its thousand decompositions and recompositions is what has been called, more or less properly, Impressionism because by it a painting becomes the impression of a moment experienced in nature. The jokers of the press have started from there to caricature the Impressionist painter catching, so to speak, his impressions on the wing in half a dozen shapeless brush strokes; and it must be admitted that certain artists have unfortunately warranted these attacks by contenting themselves with sketches that are far too rudimentary. As far as I am concerned, it is true that one has to apprehend living nature in the expression of an instant; only, this instant must be fixed on the canvas for ever by a fully considered composition. In the end, nothing solid is possible without work. . . .

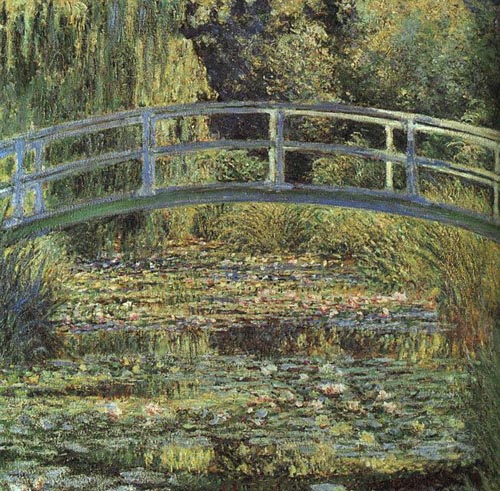

Claude Monet, Waterlilies at Giverny (1899)

Students from this Class at Giverny, 2013 Even in a photograph you can see that, as Zola points out, the actual colors of the vegetation are more complex than those usually represented in academic painting. |

The public is dumbfounded when it comes face to face with certain canvases painted in the open at specific hours; it stands gaping before blue grasses, violet-colored soils, red trees, waters running with all the motley of the rainbow. And yet the artist has been conscientious; he has, perhaps, by reaction, slightly exaggerated the new tonalities his eye has noted; but, when it comes down to it, the observation is absolutely true, nature has never adhered to the simplified notation that the established schools use to treat it. [But it is this last to which the public is used.] Hence the laughter of the crowd faced with the Impressionist paintings, despite the good faith and the very honest, naive efforts of the young painters.

They are taken for pranksters, humbugs, charlatans making fun of the public and drumming up publicity around their works, when they are, on the contrary, severe and principled observers. What seems to be ignored is that most of these contenders are poor men who work themselves to death, sometimes quite literally from misery and weariness. Strange humbugs, these martyrs for their beliefs!

This is, then, what the Impressionist painters have to offer: a more exact examination of the causes and effects of light, exerting its influence both on color and design. They have been justifiably accused of drawing their inspiration from Japanese prints. . . . It is certain that our dark schools of painting, the bituminous-minded work of our established schools, has been surprised and forced to rethink things when faced with the limpid horizons, the beautiful vibrant spots of the Japanese water-colorists. There was in these works a simplicity of means and an intensity of performance which struck our young artists and drove them on to this path of painting soaked in air and light -- a path which all the talented newcomers take today. . . .

The great pity is that this new formula which they all bring scattered in their works, not one of the artists of the group has realized it powerfully and definitively. The formula is there, endlessly divided; but nowhere, in any one of them, do we find it applied by a master. . . . Yet, while we can take objection to their personal incapacity, they remain none the less the true representatives of our time. They have plenty of gaps, their workmanship is too often slack, they are too easily satisfied, they show themselves to be incomplete, illogical, exaggerated, ineffectual. No matter: it is enough for them to apply themselves to contemporary naturalism in order to find themselves at the head of a movement and play a great part in our school of painting.