REALISM, HISTORY AND TIME

Linda Nochlin, Realism (Middlesex, England: Penguin Books, 1971), pp.23-29.

Gustave Courbet, After Dinner at Ornans (1849) |

A new and broadened notion of history, accompanying a radical alteration of the sense of time, was central to the Realist outlook. Furthermore, new democratic ideas stimulated a wider historical approach. Ordinary people -- merchants, workers and peasants -- in their everyday functions, began to appear on a stage formerly reserved exclusively for kings, nobles, diplomats and heroes. 'Give up the theory of constitutions and their mechanism, of religions and their system', demanded Hippolyte Taine, apostle of the new historical approach, 'and try to see men in their workshops, in their offices, in their fields, with their sky, their earth, their houses, their dress, tillage, meals, as you do when, landing in England or Italy, you remark faces and gestures, roads and inns, a citizen taking his walk, a workman drinking.' This insistence on the connection between history and experienced fact is characteristic of the Realist outlook. As Flaubert pointed out in a letter of 1854 : 'The leading characteristic of our century is its historical sense. This is why we have to confine ourselves to relating the facts.' A true understanding and representation of both past and present was now seen to depend on a scrupulous examination of the evidence, free from any conventional, accepted moral or metaphysical evaluation. . . . Applying this attitude to art, Courbet declared in 1861 that 'painting is an essentially concrete art and can only consist of the presentation of real and existing things. It is a completely physical language, the words of which consist of all visible objects; an object which is abstract, not visible, non-existent, is not within the realm of painting.'

It is hardly paradoxical that the era in which history was canonized as a scientific (or pseudo-scientific?) discipline also saw the end of History Painting -- that time-honoured pictorial assertion of permanent values and eternal ideals centred around the nexus of heroic antiquity. Painters did not cease to paint subjects from Greek and Roman history: far from it. And certain critics urged a return to the appropriate 'grand manner'. But what they now produced were, for the most part, historical genre paintings: scenes from the everyday life of Greece and Rome, scrupulously accurate in costume and setting, and as devoid of elevated sentiment as of noble form. In other words, History painters had become anecdotal painters of history, and most of them found the decor and picturesque costumes of the Middle Ages or the Renaissance more sympathetic than those of the ancient world . . . . Gerome's Death of Caesar and Poussin's Death of Germanicus are both set in the ancient world; but Gerome's photographic veracity and insistence on the concreteness of a specific historical event could hardly be further removed from Poussin's elevated generalization and moral distancing. No matter what his choice of subject or his professed attitude to the nature of art, Gerome would seem, on the evidence of his work, to have shared Courbet's view that painting was essentially an art concrete and demanded a similarly concrete visual language. From this point of view it is simply Courbet's insistence on contemporaneity as a necessary condition of the concrete that separates the academic artist from the innovator. . . .

The Realist, of course, insisted that only the contemporary world was a suitable subject for the artist since, as

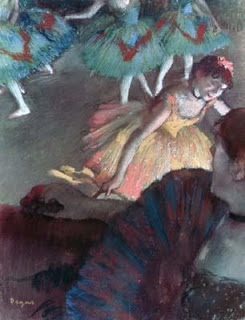

Edgar Degas, Ballerina and Lady with a Fan, 1855 |

Courbet put it, 'the art of painting can only consist of the representation of objects which are visible and tangible for the artist', and the artists of one century were therefore 'basically incapable of reproducing the aspect of a past or future century'.

The Realists held that the only valid subject for the contemporary artist was the contemporary world. 'II faut etre de son temps' [“It is necessary to be of one’s time.”] became their battle-cry. 'I hold the artists of one century basically incapable of reproducing the aspect of a 'past or future century', wrote Courbet. 'It is in this sense that I deny the possibility of historical art applied to the past. Historical art is by nature contemporary. Each epoch must have its artists who express it and reproduce it for the future . . . The history of an era is finished with that era itself and with those of its representatives who have expressed it'.

As Realism evolved, the demand for -- and conception of -- contemporaneity became more rigorous. The 'instantaneity' of the Impressionists is 'contemporaneity' taken to its ultimate limits. 'Now', 'today', 'the present', had become 'this very moment', 'this instant'. No doubt photography helped to create this identification of the contemporary with the instantaneous. But, in a deeper sense, the image of the random, the changing, the impermanent and unstable seemed closer to the experienced qualities of present-day reality than the imagery of the stable, the balanced, the harmonious. As Baudelaire said: 'modernity is the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent'.

This insistence on catching the present moment in art -- whether the encounter of Courbet and his patron on the road to Sete in The Meeting ], the corps de ballet making a reverence in a Degas or a chance effect of light or atmosphere in a Monet landscape - is an essential aspect of the Realist conception of the nature of time. Realist motion is always motion captured as it is 'now', as it is perceived in a flash of vision.

Gustave Courbet, A Burial at Ornans (1849-50)