From Raymond Rudorff, Belle Epoque,

The officially sponsored artistic life of Paris was centred around the yearly Salon which was held in the premises of the Palace of Industry on the Champs Elysees. It was a meeting place for fashionable society, it was there that all that was recognised as French art was displayed, and it was there that painters could hope to sell their works to collectors and attract the attention of wealthy, influential patrons. It was in the Salon that a new painter could make a reputation, gain the esteem of the critics, and win his first medal, thus starting along the path that led to important state commissions, official decorations and perhaps membership of some august body like the Institute of France. Few one-man exhibitions were held. There were less than a dozen art galleries of any importance before 1900. Dealers were few, and for any painter or sculptor to break into the market, find favour with collectors and eventually see his work sold in thousands of steelengraved reproductions, the prizes awarded by the Salon juries were all-important.

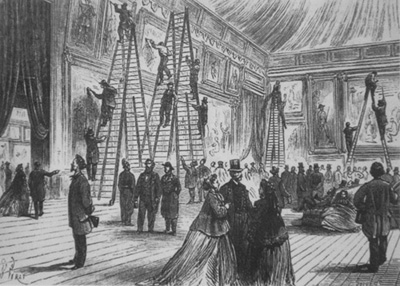

The Salon exhibition would be inaugurated by the President of the Republic [after the 2nd Empire was replaced by the 3rd Republic in 1871] in the morning, in the presence of numerous officials and artists. In the afternoon, the private view or vemissage would be held. This was the great day for Paris's leading fashion houses who would launch their newest styles. All the great names in Paris society would attend. After the President had performed the opening ceremony and dutifully toured the rooms with his retinue, uttering a few ritual phrases of appreciation here and there, artists and officials would go to the elegant Restaurant Ledoyen nearby for lunch before returning to meet their friends and admirers. The Salon would be crowded by generals and academicians, politicians and journalists. Celebrities from all walks of life would turn up to admire and be admired, and to pay homage to what was generally believed to represent the summit of the French artistic genius.

For days after this event, magazines and newspapers would publish long columns devoted to the exhibition, describing each of the main "novelties' in detail and lavishing praise on the leading favourites.

The paintings on view in Salon after Salon was all basically the same and seemed destined to continue unchanged indefinitely. The works that Paris society of the later 19th century expected to see and admire were a collection of costume pictures illustrating such dramatic events as the murder of Julius Caesar or the Fall of Babylon, nudes in the approved Graeco-Roman manner, sentimental scenes of daily life, domestic incidents, landscapes and battle scenes, these last being especially popular and mostly inspired by incidents in the Napoleonic and Franco-Prussian wars. Such pictures were not expected to be adventurous or experimental since it was taught and it was believed by most people that the purpose of French art was to instruct, adorn, edify and exalt.

B. Perat, Private Showing at the Salon, Paris (1866)

Honoré Daumier, Triumphal March (1855)

[An artist is optimistically approaching the Salon with his paintings.]

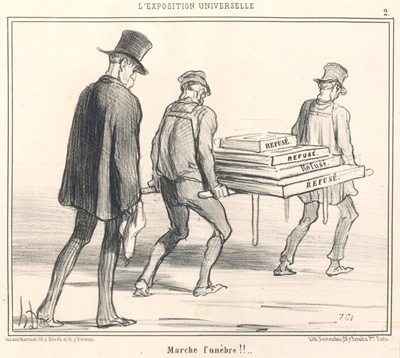

Honoré Daumier, Funeral March (1855)

[An artist is leaving the Salon Jury with all of his paintings maked "Refused"]