From Raymond Rudorff, Belle Epoque,

The Artistic Revolution, Part 1

The "masters" were practically regarded as public servants. They believed it was their duty to maintain the traditions of French civilisation. Technical skill was considered all-important. The picture had to be based upon careful drawing in the classical manner and the colouring had to be orthodox and realistic. The figures had to be lifelike and the more carefully rendered detail the artist could cram into his composition, the more likely he was to be admired and praised for his "realism". As it was believed that there was only one way to paint a picture, as taught in the academies and art schools, the originality of a painting tended to depend upon the artist's choice of subject. When, in 1878, one of the most popular painters of the day, Henri Gervex, created a sensation at the Paris Salon with a picture called Rolla, it was not on account of any radical innovation in pictorial technique. It was simply because the subject -- a lover gazing at the naked body of his mistress sprawling on an unmade bed -- was considered to be ''daring". Twenty years later, the situation was basically the same: to be successful, a painter was expected to be a meticulous draughtsman, to use conventional colours, to pay as much attention to the smallest detail as to the main figures in his composition, and to choose an "interesting" subject.

Henri Gervew, Rolla (1878)

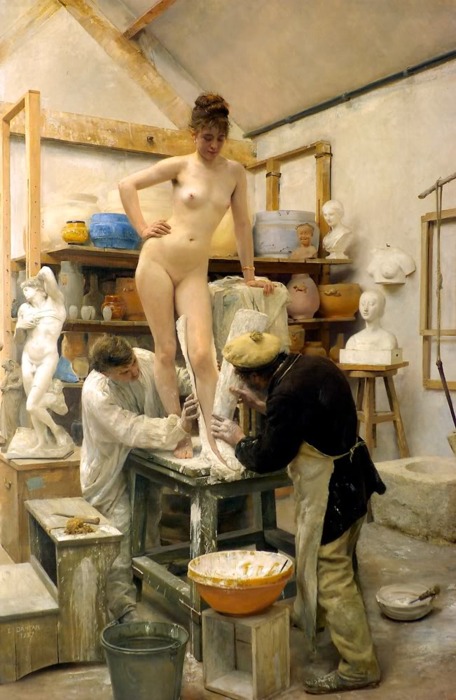

Edouard Joseph Dantan, A Cast from Nature (1887)

Academic art seemed to have come to the end of its road. Most of the critics, the public and buyers generally agreed that French art had reached an ideal state and was destined to continue as before, with each new generation of artists faithfully adhering to established styles and standards. Art was a system and, for those who conformed to the system and became popular, the rewards were great. Once a painter was weil established, he led a comfortable life. The most successful artists lived like princes in great mansions in the most fashionable parts of Paris, magazines published photographs of them in their huge studios, they were welcome in high social circles and were given important commissions and honours by members of the government and civil service. They virtually monopolised the art market, dominated the exhibitions and became members of juries at the Salon. No matter what they painted, the successful painters all shared a common feeling that they belonged to the same caste. An academic or Salon painter was a member of a club with clearly defined and unchangeable rules. They were public figures and established, officially approved representatives of their nation's culture.

There was no question of the artist being a man outside society, a rebel shut away in his studio struggling to express a personal emotion or view of life in an idiosyncratic manner which disregarded the way other artists painted and the methods by which art was taught. They were at peace with a society which they served and which honoured them in return, and they earned vast sums.

The academics had learned how to paint in a certain manner and -- perhaps even more important -- they knew exactly what they were expected to paint. The idea that an artist could change his style and technique, mature and transform his art as he followed the impulsions of his genius was alien to them. Similarly, the idea that the officially accepted attitude to art could be stultifying, outmoded or reactionary never occurred to most artists and critics. They would have been deeply hurt if anyone had called them either reactionary or unimaginative. . .

With the academic painters and such collectors dominating the Parisian art market and public taste, it was extremely difficult for any truly creative, independent-minded and innovating artist to make a reputation and a living. If a newcomer wished to enter the privileged circle of painters who earned fortunes and were awarded official honours, he would have to conform to the system which had been established. He would have to learn a conventional idea of artistic beauty which was taught in the art schools "as one teaches algebra," as the architect Viollet-le-Duc once remarked.

He would work under an academic master who preached the virtues of ''classical" drawing and composition and he would take his works to be inspected by the Salon jury each spring and abide by their judgement. He would have to learn how to please the public, never to provoke or disconcert it. Above all, he would have to learn the importance of never puzzling the spectator. A painting was not supposed to be difficult, to make the viewer think, or to contain any significance not immediateIy apparent to the simplest mentality.

Such art had become static. The "dear masters" were believed to have raised painting to a state of perfection. Once an aspiring new artist had reached their level, it was difficult to see in what way he could progress any further. Art had become an officially approved system. It had been so advantageous and profitable to painters like Meissonier, Gerome and Bouguereau that they were determined to maintain it until Doomsday, and by the 1890's it still appeared dominant. It was defended not only by the Salon artists themselves but by most newspaper critics, members of the Institute, art teachers, advisers to dealers and civil servants in the government. They all saw themselves as absolute experts on what was and what was not Art and they were popularly and officially recognised as such. The result of their dictatorship over public taste was that in the 1890's most of the painting on display in Paris was substantially the same in spirit, style and content as that which had been seen in the 1870's. Even in the first years of the 20th century, such an authoritative guide book as Baedeker's was telling the visitor to Paris that "a survey of CONTEMPORARY PAINTING may be obtained by visiting the Hotel de Ville, the Sorbonne, the Mairies, the Luxembourg, the annual Salons and the smaller exhibitions".

Such a situation was not without its critics. It was fiercely condemned by Octave Mirbeau, a journalist and writer on a;t who was one of the few to campaign for a new kind of painting and to point out that it was not in the Salons that fresh and original talent was to be found. Writing in the Echo de Paris in May 1892, he said:

''Painting has put art to flight. You no longer see it in the exhibitions which have now become the great vomitoriums of universal mediocrity, nor in the sales where the inexpressible bad taste, the overwhelming ignorance and the intellectual platitude of contemporary art are so crudely displayed.

" Twenty artists suffice to immortalize the great epochs of art. We have them, these twenty privileged beings who are as worthy of admiration as the most illustrious geniuses of times past. But who would dream of recognising them among this deafening pell-mell? They themselves, disgusted by this increasingly all invading, increasingly degrading promiscuity, move away and shut themselves up. And far away from the hubbub, solitary and happy, they are working at things we do not understand."

Mirbeau was right. France did have a number of truly great and original artists who worked "far away from the hubbub" of Paris's fashionable art world. while academic art fossilised in the complacent atmosphere of the Salon and leading art galleries, a revolution was taking place in French painting and gathering momentum towards the final decade of the century.

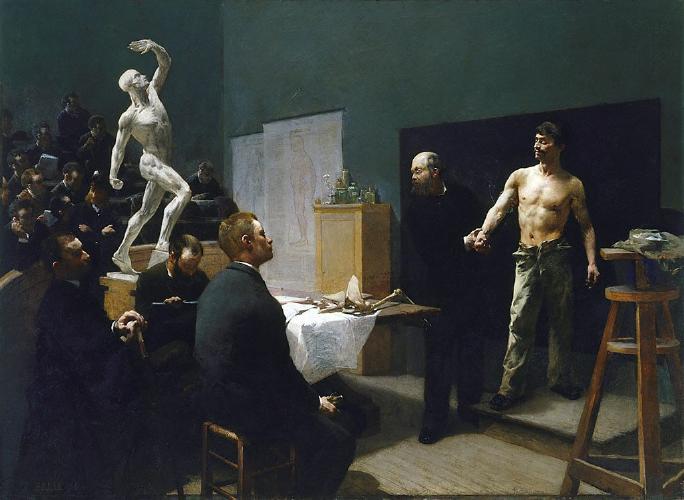

François Sallé (France, 1839-1899) The anatomy class at the Ecole des Beaux Arts (1888)