The Career of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904)

Gérôme was one of the most successful artists in Paris during the second half of the 19th century. Looking at his career can provide insights into the conditions that shaped art in this period. As you read the short biography below, think about the ways in whih the patterns that led to success for Gérôme also drew him and other successful artists of the period to produce the kind of art approved by the art establishing and by much of the art buying public.

|

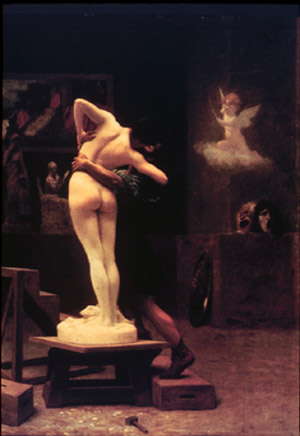

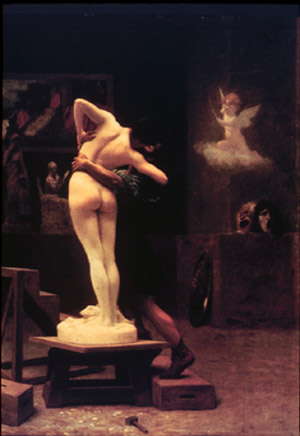

Gérôme, Pygmalion and Galatea

(1890) |

In 1840, just as he was turning seventeen, Jean-Léon Gérôme moved from a small provincial city in France to Paris. The son of the goldsmith, he had demonstrated great aptitude in both the classics and the sciences at the local lycée (high school), but, like many youths of the 19th century, his real passion was to become an artist. At the age of fourteen he had begun studying with a local painter, following a torturously systematic course of instruction that began with study of the dimensions and placement of the eyes, nose, mouth, and ears and then moved slowly through painting the entire face, the feet, the hands, etc, until after several years Gérôme was allowed to paint the entire body. His accurate copy of a painting by an established artist finally convinced his father that Jean-Léon might have sufficient talent to go to Paris to begin a career as a painter, although most of the rest of his family feared that he would be lost forever.

|

The copy that convinced his father also earned Gérôme a place in the atelier (studio) of the well-known painter Paul Delaroche. In Paris he learned about the technique of oil painting from his master, studied copies of Greek statues, attended classes at the École de Beaux-Arts (the official art school), and copied famous paintings in the Louvre. He became one of the leaders of a new generation of artists, he partook of some of the milder pleasures of the bohemain life of the city , and he may have supported some leftist positions in the aftermath of the Revolution of 1848. But he and his friends chose to call for new directions within the slow development of Western art, rather than support a major break with tradition. They found the new emphasis on realism appealing, but, unlike more radical painters such as Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) who abandoned the classical subject matter that had long dominated European painting and focused on scenes of contemporary life, Gérôme and his friends sought to apply a new sense of realism to historical and mythological subjects.

|

Gérôme, Cleopatra before Cesar

(1866) |

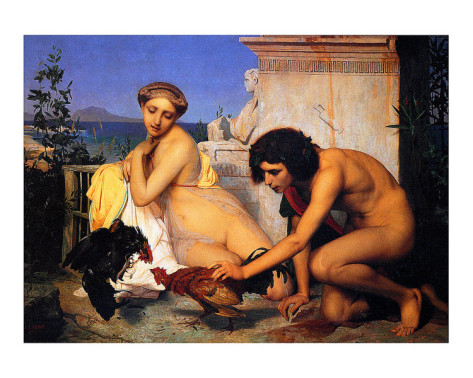

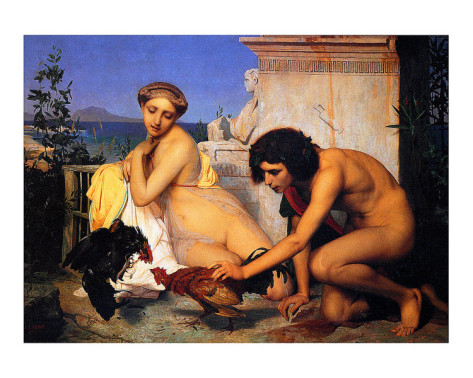

Gérôme, The Cock Fight, (1846) |

Gérôme mastered the technique of producing a painting that obliterated all traces of brush strokes and produced the illusion of a kind of window on reality. His painting The Cock Fight was “skyed” (hung quite high) among the many paintings accepted into the Salon [official art show] in 1847, but it attracted the attention of poet and critic Théophile Gautier, and his review made Gérôme famous. His careful rendering of the human form and concern with historical accuracy appealed to the world of academic art and to potential patrons. The eroticism of much of his work disturbed a few critics, but the fact that most of them were set in other historical periods or cultures made them acceptable to most of his audience. |

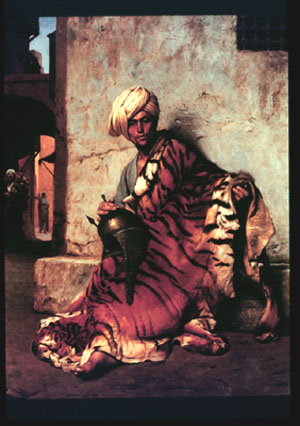

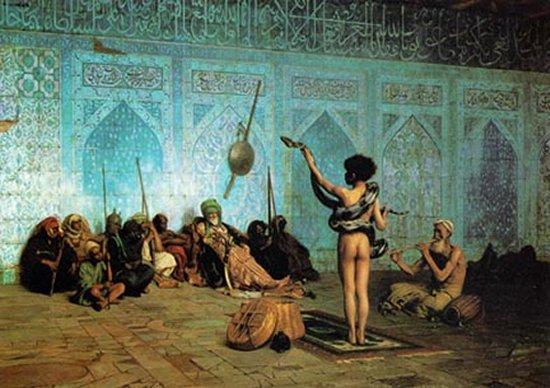

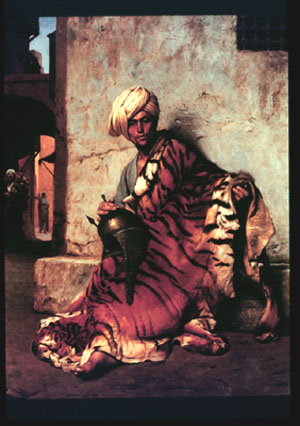

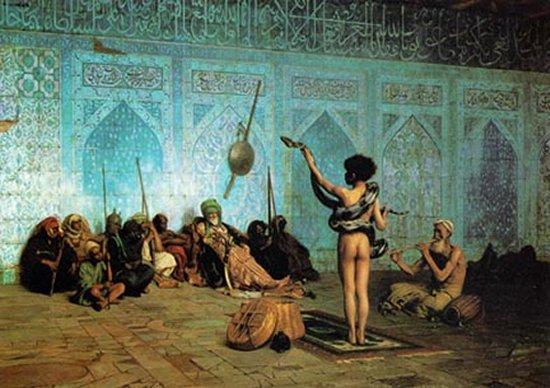

| As years passed In subsequent years Gérôme became increasingly successful. His paintings were regularly accepted into the annual Salons, and he twice received gold medals. He became a teacher at the École des Beaux Arts, and he received commissions for portraits and for paintings to decorate churches and public buiildings. But his real love was capturing a moment in time – either by recreating with great detail a moment from a early historical period or by recreating exotic visions of daily life in the Islamic world. He traveled extensively in the Middle East, and in a period in which there was great concern with gaining and keeping colonies, he provided the French with visions of fierce nomadic tribesmen, Muslims praying, and naked women in harems. Throughout his life Gérôme remain loyal to the belief that “the interpretation – healthy, strong and true – of Nature is the only path that leads to masterpieces,” but he rejected what he called “commonplace and indiscriminate realism” that portrayed everyday scenes without an enobling or enlightening message. But As he grew older, he was increasingly out of touch with newer directions in art, and he attacked them strongly. He described Impressionist painting as “insipid and badly executed: badly |

Gérôme, Pelt Merchant of Cairo

(1869) |

Gérôme, The Snake Charmer (c.1883) |

drawn, badly painted, and stupid beyond expression.” He boasted that “I claim the honor of having waged war against these tendencies, and shall continue to combat them.” In 1884 he objected to a showing of the paintings of Edouard Manet at the École des Beaux Arts, and In 1897 he sought to prevent the inclusion of the works of Gustave Caillebotte in the official modern art collection at the Luxembourg Museum. At the Universal Exhibition of 1900 he is said to have tried to prevent the President of France as the latter entered the Impressionist exhibit, saying “Stop, monsieur le Président, the shame of French painting is in there.” And late in his career he unsuccessfully sought to prevent the entry of women into the École des Beaux Arts. |

| By the time of his death at the age of 79 in 1904 Gérôme was clearly out of touch with contemporary developments in art, but his conservative views on modern art represented those of a significant portion of the French art public, and the 57 years that he had been exhibiting at the Salon and the 40 years he taught at the École des Beaux Arts had had a significant impact on the art of the second half of the 19th century. |

Gérome in the uniform of Grand Officer of the Legion of Honor, 1900

|