David W. Galenson and Robert Jenson, "Canvases and Careers: The Rise of the Market for Modern Art in the Nineteenth Century"

Below is an excerpt from a book by two economists reevaluating the claims made in the 1960s by two sociologists (Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White) in Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World. In this passage Galenson and Jenson are restating the claims of the earlier authors about the forces that retarded innovation in French art for much of the 19th century.

This excerpt provides a good general view of the social world within which 19th century French painters worked. As you read it, ask yourself these questions:

- In what ways were the attempts to change French art limited by the institutions within which artists operated?

- What kinds of art were be favored by this system and what kinds discouraged?

- What arguments might the defenders of this system advance to justify the roles of the Academy, the Salon, the Ecole des Beaux Arts, and the awards given to artists?

- In what ways did this system support the work of those artists that it favored? Why should those were successful within this system defend tradition?

- What was apt to happen to a young artist who tried to take art in a radical new direction?

I. 2. Summary of Canvases and Careers

Canvases and Careers describes a change in what the authors refer to as the institutional structure of the 19th-century French art world from what they call the Academic system to the dealer-critic system. This section briefly summarizes the authors' account of these two regimes.

The Academic system was controlled by the government’s Academie de Peinture et Sculpture [Academy of Painting and Sculpture](hereafter the Academy). Aspiring artists were educated at the government's École des Beaux-Arts [School of Fine Arts], where they were taught to use traditional methods to emulate the work of their teachers. While at the Ecole students advanced if they passed annual examinations and participated in a series of contests designed to identify the most talented. After graduation the goal of young artists was to display their paintings at the Salon, the great annual or biennial exhibition that was the French art wor1d"s principal showcase for new work. Admission to the Salon was regulated by a jury. Although its composition varied, a majority of the jury’s members were usually associated with the Academy. The Academy consequently used the Salon as a continuing means of control over artists: not only acceptance of their paintings but preferential placement of their work in the many crowded halls of the Salon, and access to themedals that the jury awarded to recognize distinction were all central to building the reputations that would create a demand from private clients for the artists' work.

Students at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, late 19th century

Paris Salon, 1847

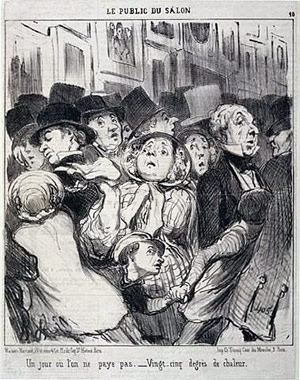

Daumier, Free Day at the Salon (1852)

The Paris Salon, unlike comparable institutions in other Western nations, dominated its nation’s art until at least the third quarter of the century. This occurred not because there was an absence of rival exhibition venues. Rather both artists and their publics sustained the belief that the Salon was the only truly legitimate arena tor exhibiting and evaluating works of art. So deeply did the Parisian art world hold to the certifying function of the Salon that this faith survived the many controversies over the judgment of Salon juries, over who voted for the juries, and over who served on them. Such criticism of the Salon had begun as early as the 1830s and yet no other exhibition was able to acquire a comparable sense of legitimacy within the community of artists until the Impressionist exhibitions of the 1870s and 1880s. As Gustave Courbet observed following the refusal of all the paintings he submitted to the Salon of 1847, “It is bias on the part of the gentlemen of the jury: they refuse all those who do not belong to their school, except for one or two, against whom they can no longer fight, such as MM. [monsieurs] Delacroix, Decamps, Diaz, but all those who are not as well known by the public are sent away without a word. That does no bother me in the least, from the point of view of their judgment, but to make a name for oneself one must exhibit, and, unfortunately, that is the only exhibition there is.”

Until 1874, showing at the Salon was a necessary condition for establishing an artist’s reputation and career in Paris. Thus no major French artist was able to forego showing at the Salon, at least at the beginning of his or her career, until the last quarter of the century. After 1874 major artists such as Paul Gauguin and Georges Seurat no longer debuted at the Salon, but discovered they could establish their careers outside the review of the Salon's juries.

Favored artists were rewarded by the state and the Academy in a number of ways. One was through state commissions. A second was state purchases, typically selected from works exhibited at the Salon. Works of art acquired in this way were generally distributed among Frances provincial museums or Paris's museum for living artists, the Luxembourg. A third means of official recognition lay in Salon prize medals, awarded as first, second, or third-class medals, and accompanied by a cash prize. . . .

The government further buttressed the Salon medal system by offering another set of medals awarded at the various art exhibitions held in conjunction with the great Expositions Universelle of 1855, 1867, 1876, 1889, and 1900. The French artists who received these special medals and higher cash prizes almost invariably had previously medaled at the Salons. With so many opportunities available . . . important French Salon artists who debuted after the first quarter of the century often earned at least three medals over their careers and sometimes more.

Successful Salon careers then positioned artists to take advantage of additional components of the award system that the Academy and the state could offer artists. The first was appointments to desirable jobs. These included teaching positions at the Ecole de.s· Beaux-Arts and the coveted position of director of the French Academy in Rome. The second was admission to the Legion of Honor, created by Napoleon. The Legion was divided into four classes of membership, beginning with Chevalier followed by the Officier rank. then Commandeur, and at the top the Grand Cross. The third type of honor for the most favored artists was election to the French Academy.

The award system offered artists a measure of financial security by building their reputations steadily over the course of their careers. While medals and knighthoods were not in themselves sufficient to guarantee the personal fortunes of artists, these honors significantly publicized their careers in amanner entrely unavailable to artists outside the Salon system. Salon celebrities were given favored access to critical and public attention, and thus served to attract dealers to buy their work and to act as agents on their behalf.

School of Thomas Couture, 1854-55