Subject Matter, Styles, and Markets

Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), pp.90-91

The official ideology persisted in spite of many corruptions, and it led to sporadic harshness toward paintings not in keeping with "the great tradition." To understand the

Nicolas Poussin, Midas and Bacchus (1629-1630) |

staying power of this ideology, one must consider the way in which it bound social and psychological ideas about the artist to specific types of painting. Let us return, for a moment, to the Academic theoreticians of 150 years earlier:

Thus, he who paints landscapes perfectly is above the one who makes only [pictures of] fruits, flowers or shells. He who paints living animals is more estimable than those who represent only things that are dead and motionless and since the figure of man is the most perfect earthly work of God, it is certain also that he who gives himself to the imitation of God in painting human figures is more excellent than all others.... There are different workers who apply themselves to different subjects. It is an established fact that to the degree in which they occupy themselves with more difficult and noble things, they separate themselves from that which is lowest and most commonplace. [From Felibien, Conférences de l'Académie Royale de Peinture et Sculpture , London, 1705.]

Very obviously, these notions are linked to a social hierarchy within the artistic profession:

Thus, genius has several degrees, and nature has endowed some with one ability, others with another; not only in the diversity of professions but still more among the different parts of the same art or the same science. In painting, for example, one may have a talent for landscape, for animals or for flowers. [From Felibien, Conférences de l'Académie Royale de Peinture et Sculpture , London, 1705.]

These words, so tied up, as we have seen, with changes in the artist's social status, come echoing down to the nineteenth century. Even as late as 1863, the droves of still lifes submitted to the Salon were rejected wholesale. Academic conservatism is not merely a tired carryover from the past; at its stubborn roots are vital social meanings.

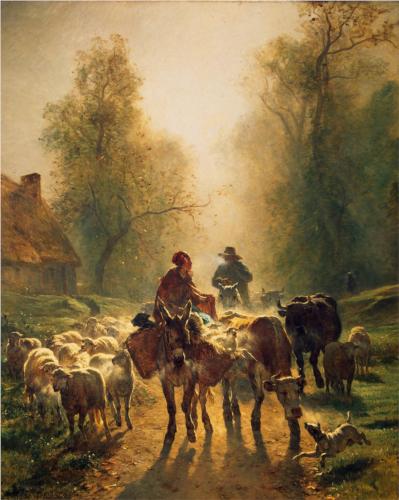

Constant Troyon, On the Way to Market (1859) |

The central struggle, as seen by the art world of the time, was at first between elevated history painting and saccharine genre. Genre painting won. Meissonier, delineator of highly finished genre scenes in wondrously small sizes, was elected to the Academy in 1861. Three hundred provincial museums there might be, government commissions for public works there might be, but the only possible paid destinations for the rising flood of canvases were

the homes of the bourgeoisie. History painting had not and never would rest comfortably in the middle-class parlor. "Lesser" forms of image art-genre, landscape, still life-did.

History painting of a debased sort, scenes of brutality and terror purporting to illustrate episodes from Roman and Moorish history, were Salon sensations. On the overcrowded walls of the exhibition galleries, the paintings that shouted loudest got the attention. The state even bought some of these popular horrors, but although they were good entertainment for a Sunday afternoon, no bourgeois family would ever want one in the home. Genre painting, painting that shows a story, was a development related to the increasingly anecdotal character of contemporary history painting. From the era of the First Empire, genre painting began to crowd the walls of the Salons. In these early years of the century, a scene of everyday life was often related to contemporary national events. There are titles like: Soldier's Departure, Young Woman Weeping Over a Letter, and Abandoned Innocence. Troubador subjects, romantic little scenes of the middle ages, appeared early under the guise of "historical anecdote." And military history painting focused more and more on incidental action rather than on formally arranged central figures. . . .

In the trend toward genre painting there was also an attempt to solve the problem of finding a secure career in painting. More and more genre painters specialized, taking a particular subject and making a career of it. Animal painting was a very popular field. There were painters of farm horses and cattle, like the fabulously successful Rosa Bonheur, and the Barbizon painter Troyon, who was at one point so pressed for his paintings of cows that he hired Boudin to brush in the landscape backgrounds in a hurry.15 One Troyon cow was very much like another, so no particular painting was singled out; instead the buyer was attracted to any Troyon rural scene -- if he liked cows! There were the painters of picturesque military scenes, like Ziem. Others specialized in cutting the heroic orientalism of Delacroix down to genre size.