The Salon: Proving Ground

Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), pp.27-32.

As you read this description of the Salon, think about the difficulties a young artist at the time would have had in successfully deviating from the officially approved classical styles of the period.

The central event in the French painting world of the nineteenth century was the Paris Salon [i.e. the official exhibition of painting and sculpture]. Significant  historical changes in its structure brought out different, conflicting purposes and meanings. What was it? An exhibition of and for a professional group? A show put on by a benevolent state? Or an enormous picture shop? No one was quite sure. Everyone had his opinion and expectation. The result was a great mismatch in cultural and social meanings. This is an important theme in investigating the Salon as an instrument of control.

historical changes in its structure brought out different, conflicting purposes and meanings. What was it? An exhibition of and for a professional group? A show put on by a benevolent state? Or an enormous picture shop? No one was quite sure. Everyone had his opinion and expectation. The result was a great mismatch in cultural and social meanings. This is an important theme in investigating the Salon as an instrument of control.

Important (though rather backhanded) evidence that a social control exists comes from observation of what happens when the rules are changed. . . . [In 1791 during the French Revolution any French artist was free to exhibit in the Salon] The jury reappeared in 1798, a result of protests by artists and officials alike. By the beginning of the First Empire, it became a an established feature of the Salon. In the 1806 Salon the number of paintings exhibited was back down to 573 by 293 painters, and the total number of works was down to 704.

The jury's main function within the confines of eighteenth-century Academy exhibitions had been as a watchdog on morality. Now the jury was to judge merit. Later this ostensible task became obscured as the jury struggled to cope with and keep down the number of works to be exhibited.

There is no nineteenth-century example of a completely open Salon, previously announced as such. It is a fair guess that the response to one would have been astounding. In 1848, 5362 works had already been submitted when the revolutionary government announced that the Salon would be "free," that is, all the works on hand would be hung. . . .

The membership of the jury, which ranged in size from 8 to 15, was determined by varying methods. Until 1848 the Academy had the majority, electing its own members to the jury while the state had a minority share of appointed government officials. From 1849 on, the jury was partly state appointed, partly elected by all artists who had exhibited in prior years or, as a variant in some years, those who had been "medaled" at previous Salons. The proportions varied with changes in political winds. It is notable that those jurors elected by the artists were, almost without exception, either Academy members or men of conservative leanings. The same names appeared on the jury again and again.

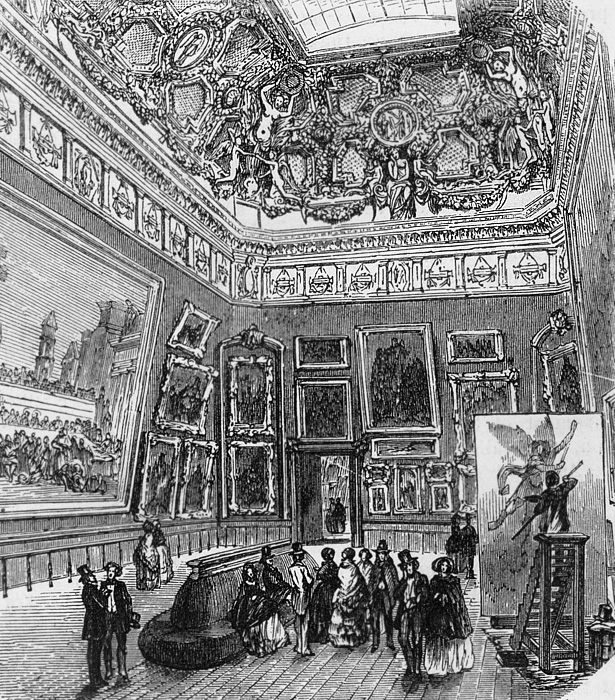

By the middle of the Second Empire the Salon was being held in the Palais d'Industrie the enormous exhibition hall built by Napoleon III in imitation of Victoria's Crystal Palace. Contemporary photographs, journalistic and literary accounts, and lithographs provide a vivid picture of the mid-nineteenth-century Salon. Tiers and tiers of paintings reached to the ceiling. Crowded halls, noise, and confusion were the hallmarks. Public (paid) attendance often reached 10,000 per day. The jury for painting had, as we have seen, a thankless task: to view as many as 5000 paintings and agree upon acceptances and rejections in a limited period of time. The "hanging committee" were no less harassed; it was their job to direct the placement of works, arrange catalogue numbers, and listen to endless pleas, in person and by letter, from painters who felt that their unfavorable placement was an insult.

Constant changes in Salon rules reflect the storms of protest that harassed the different governments. It was evident that the Salon was a highly unsatisfactory institution to most artists, and yet pictures kept coming in by the carload every year. The painter could not live with it -- but neither could he do without it under the existing system.

A Salon medal, press publicity, the faint hope of a state commission were the lures that set painters furiously to work around January of each year to finish their Salon offerings in time for the late March or early April deadline. Once a medal of a certain class had been won (specifications and number of medals varied over the years) a painter was "hors concours": automatically accepted for the Salon. In 1864, for instance, 367 out of 3478 works exhibited were hors concours. Cash prizes accompanying medals were fairly substantial; for example, in 1853, 250 francs were given with third, 500 francs with second, and 1500 francs with first-class medals, plus 4000 francs with the single Medal of Honor instituted in that year. But single paintings by favored masters commanded much more on the market, so that probably few thought of the medals for the money attached.

Two contradictory but avowed purposes were contained in the institution of the Salon. It was intended as the main instrument for review, reward, and control of painters seeking official recognition. In this professional aspect it continued the obstacle course of contests familiar to students. At the same time the Salon was a vast show put on in an age of expositions for the public at home and elites abroad. On the one hand, the judgments of the official elite were considered sacred to the welfare of the profession and the upholding of its standards. On the other hand, there was a strong faith in the judgments of the public. The building of reputation and the sale of works were linked to this faith, in the painter's view of the Salon.