TRAINING: OFFICIAL ROUTE TO SUCCESS

Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), pp.18-19.

As you read this description of the path to success within the art world dominated by the French Academy of Arts, think about the difficulties a young artist at the time would have had in successfully deviating from the officially approved classical styles of the period

Painting was becoming a profession in the middle-class sense. Methods of advancement in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts were as prescribed in principle as those of St.-Cyr [the French military academy] .Comforted by this, bourgeois fathers became more willing to send their sons through this official painting system where application and perseverance would produce a publicly discernible record of advancement.

French military academy] .Comforted by this, bourgeois fathers became more willing to send their sons through this official painting system where application and perseverance would produce a publicly discernible record of advancement.

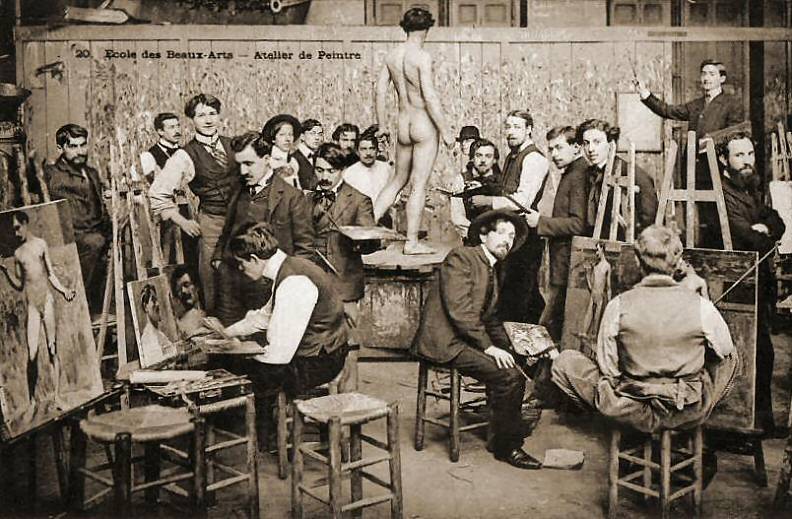

The Ecole des Beaux-Arts, outgrowth of the prerevolutionary Academy's Ecole du Louvre, was the basic step for the uninitiated young artist. Training was long and rigid, consisting entirely of drawing, until the reforms of Count Nieuwerkerke late in the Second Empire. From the copying of drawings the student graduated to plaster casts of classical statues and finally to the living model. From the first entrance competition where the weeding-out process finally produced perhaps 40 admittees and 80 continuing students, life at the Ecole was a series of contests. There were yearly medals for the best works and all who did not win them were required to keep on taking the annual examinations. The culminating contest of the student years begun at the Ecole was the Prix de Rome competition.

After the Ecole or sometimes while still attending it, the student obtained admittance to one of the painting ateliers where he paid a monthly fee to the master and was allowed to begin painting studies of the nude male or female model, which was again the basic subjects. There were a number of well-known professional teachers of painting and most of the Academy members maintained ateliers. The master appeared once a week and made his rounds, criticizing and correcting according to Academy doctrine.

Winners of the Grand or first prize in painting of the Prix de Rome contest, in addition to four years study at a comfortable salary in the French Academy of Rome, were later to have additional years in Paris at high stipends donated by wealthy friends of the official art system. They were supposed to be the principal carriers of the great tradition, although after Ingres (in 1801) the average caliber of winners gave pause to many of even the most conservative academicians. At this apex the official training system functioned smoothly and predictably as the road to success.