Tzvetan Todorov,

On Human Diversity: Nationalism,

Racism, and Exoticism in French Thought (Cambridge. Massachusetts:

Harvard University Press, 1993, pp.90-94

| In this passage Tzvetan Todorov, a late 20th century Bulgarian-French intellectual, is trying to distinguish between "racism," which is a form of behavior and political action, and "racialism," which is a theoretical concept. He does not approve of either position, and he acknowledges that in practice they almost always overlap. But for purposes of historical analysis, he is trying to understand the two different manifestations of this phenomena. We can talk about whether or not you find this to be a valid approach. |

Here I must begin by introducing a terminological

distinction. The word "racism," in its usual sense, actually designates two

very different things. On the one hand, it is a matter of behavior, usually

a manifestation of hatred or contempt for individuals who have well-defined

physical characteristics different from our own; on the other hand, it is a

matter of ideology, a doctrine concerning human races. The two are not

necessarily linked. The ordinary racist is not a theoretician; he is

incapable of justifying his behavior with "scientific" arguments.

Conversely, the ideologue of race is not necessarily a "racist," in the

usual sense: his theoretical views may have no influence whatsoever on his

acts, or his theory may not imply that certain races are intrinsically evil.

[P.91]

actually designates two

very different things. On the one hand, it is a matter of behavior, usually

a manifestation of hatred or contempt for individuals who have well-defined

physical characteristics different from our own; on the other hand, it is a

matter of ideology, a doctrine concerning human races. The two are not

necessarily linked. The ordinary racist is not a theoretician; he is

incapable of justifying his behavior with "scientific" arguments.

Conversely, the ideologue of race is not necessarily a "racist," in the

usual sense: his theoretical views may have no influence whatsoever on his

acts, or his theory may not imply that certain races are intrinsically evil.

[P.91]

In order to keep these two meanings separate, I shall adopt the

distinction that sometimes obtains between "racism," a term designating

behavior, and "racialism," a term reserved for doctrines. I must add that

the form of racism that is rooted in racialism produces particularly

catastrophic results: this is precisely the case of Nazism. Racism is

ancient form of behavior that is probably found worldwide; racialism is a

movement of ideas born in Western Europe whose period of flowering extends

from the mid-eighteenth century to the mid-twentieth.

Racialist doctrine, which will be our chief concern

here, can be presented as a coherent set of propositions. They are all found

in the “ideal type," or classical version of the doctrine, but some of them

may be absent from a given marginal or "revisionist" version . These

propositions may be reduced to five.

1.

The

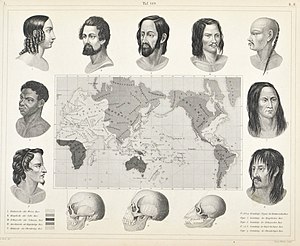

existence of races. The first thesis obviously consists in affirming

that there are such things as races, that is, human groupings whose members

possess common physical characteristics . . . From this perspective,

races are equated with animal species, and it is postulated that

there is same distance between two human races as between horses and

donkeys: not enough to prevent reproduction, but enough to establish

boundary readily apparent to all. Racialists are not generally content to

observe this state of affairs; they also want to see it maintained: they are

thus opposed to racial mixing.

The adversaries of racialist theory have often attacked the doctrine

on this point. First, they draw attention to the fact that human groups

intermingled from time immemorial; consequently, their physical

characteristics cannot be as different as racialists claim. Next, these

theorists add a two-pronged biological observation to their historical

argument. In the first place, human beings indeed differ from one another in

their physical characteristics; but in order for these variations to give

rise to clearly delimited groups, the differences and the groups would have

to coincide. However, this is not the case. We can produce a first map of

the "races" if we measure genetic characteristics, a second if we analyze

blood composition, a third if we use the skeletal

System, a fourth if we look at the epidermis. In the

second place, within each of the groups thus constituted, we find greater

distances between [p.92] one individual and another than between one group

and another. For these reasons,

contemporary biology, while it has not stopped studying variations among

human beings across the planet, no longer uses the concept of race . . .

2.

Continuity

between physical type and character. But races are not simply groups of

individuals who look alike (if this had been the case, the stakes would have

been trivial). The racialist postulates, in the second place, that physical

and moral characteristics are interdependent; in other words, the

segmentation of the world along racial lines has as its corollary an equally

definitive segmentation along cultural lines. To be sure, a single race may

possess more than one culture; but as soon as there is racial variation

there is cultural change. The solidarity between race and culture is evoked

to explain why the races tend to go to war with one another.

Not only do the two segmentations coexist, it is alleged, but most often a

causal relation is posited between them: physical difference determine

cultural differences. . . .

3.

The

action of the group on the individual The same determinist principle

comes into play in another sense: the behavior of the individual depends, to

a very large extent, on the racio-cultural (or "ethnic") group to which he

or she belongs. . . . Racialism is

thus a doctrine of collective psychology, and it is inherently hostile to

the individualist ideology.

4.

Unique

hierarchy of values. The racialist is not content to assert that races

differ; he also believes that some are superior to others, which implies

that he possesses a unitary hierarchy of values, an evaluative framework

with respect to which he can make universal judgments. This is somewhat

astonishing, for the racialist who has such a framework at his disposal is

the same person who has rejected the unity of the human race. The scale of

values in question is generally ethnocentric in origin: it is very rare that

the ethnic group to which a racialist author belongs does not appear at the

top of his own hierarchy. On the level of physical qualities, the judgment

of preference usually takes the form of aesthetic appreciation: my race is

beautiful, the others are more or less ugly. On the level of the mind, the

judgment concerns both [p.94] intellectual and moral qualities (people are

stupid or intelligent, bestial or noble.

5.

Knowledge-based politics. The

four propositions listed so far take the form of descriptions of the world,

factual observations. They lead to conclusion that constitutes the fifth and

last doctrinal proposition namely, the need to embark upon a political

course that bring the world into harmony with the description provided.

Having establish the "facts,'' the racialist draws from them a moral

judgment and political ideal. Thus, the subordination of inferior races or

even their elimination can be justified by accumulated knowledge on the

subject of race. Here is where racialism rejoins racism : the theory is put

into practice .