Day 14 -- Colonialization

Alice L. Conklin, A Mission to

Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895-1930

(Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997, pp.20-22.

of intermarriage.

The earliest advocates. of a civilizing effort in the New World -- certain

colonial administrators -- had accepted racial mixing as one obvious means

to the behavioral changes they sought. This policy, although very different

from Napoleon's plan to reintroduce all of civilization to Egypt, was at

least as open-minded. Although colonial administrators had assumed that

barbarians had no civilization of their own, their recommendation to remedy

this situation through intermarriage meant that they were not overtly

racist. How widespread this attitude was, like so much else in Enlightenment

thought, remams subject to debate. What is clear is that sometime during the

first thirty years of French rule, c mm n a tors on Algeria be an to condemn

the concept of racial mixing and, by extension, the univiersal assumptions

that underwrote it. . . .

of intermarriage.

The earliest advocates. of a civilizing effort in the New World -- certain

colonial administrators -- had accepted racial mixing as one obvious means

to the behavioral changes they sought. This policy, although very different

from Napoleon's plan to reintroduce all of civilization to Egypt, was at

least as open-minded. Although colonial administrators had assumed that

barbarians had no civilization of their own, their recommendation to remedy

this situation through intermarriage meant that they were not overtly

racist. How widespread this attitude was, like so much else in Enlightenment

thought, remams subject to debate. What is clear is that sometime during the

first thirty years of French rule, c mm n a tors on Algeria be an to condemn

the concept of racial mixing and, by extension, the univiersal assumptions

that underwrote it. . . .

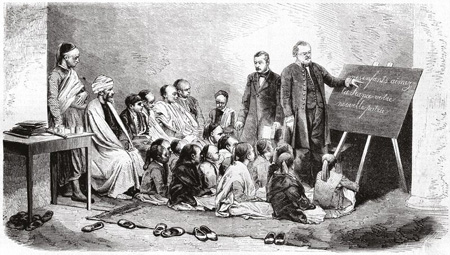

Several painful experiences acquired in the

colonization of Algeria, along with the theory of biological racism and the

onset of French industrialization at home, had predisposed the French to

alter that ideology between 1830 and 1870. By 1837, when the scientific

commission was formed, the army had met fierce Algerian resistance. French

soldiers were also dying from malaria and other tropical diseases. Indeed,

in the hostile Algerian, environment one of the greatest problems was not

only defeating the local populations, but identifying the proper hygienic

measures and civil engineering techniques that would make .the country

healthy and profitable for future settlers. After fifteen years of

educational and health care efforts -- in which metropolitan schools and

medical techniques were adopted in the colony without modification – the

Frernch also discovered a stubborn refusal by most of their new sub jects

to embrace the gifts of Western culture and ·science so "generously"

proffered. These various forms of resistance made new scientific arguments

about the inherent inferiority of other races that much more believable.

Meanwhile, with the help of modern technology and medicine, it became clear

that the white race could adapt to hot climates without intermarriage to

acclimatized "natives." These crosscurrents subdued any residual enthusiasm

for offering all of civilization's achievements to the colonized. Instead,

French definitions of what it meant to be civilized began to shift to

reflect the latest European accomplishment: the mastery of nature through

technology and science.