Day 14

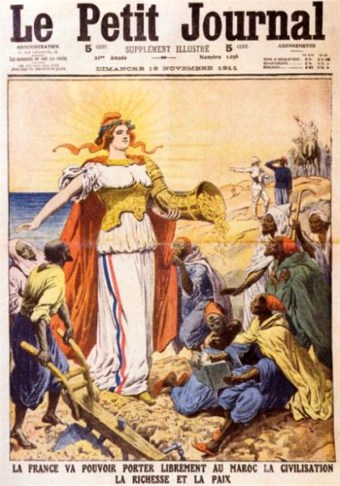

The Ideal of the Civilizing Mission

Civilization is a particularly French concept;

the French invented the term in the eighteenth century and have

celebrated the achievements of their own ever since. At no point in

modern history, however, did the French make more claims for their

civilization than during the new imperialism of the Third Republic. Of

course all European powers at the end of the nineteenth century claimed

to be carrying out the work of civilization in their overseas

territories; but only in republican France was this claim elevated to

the realm of official imperial doctrine. From about 1870, when France

began to enlarge its holdings in Africa and Indochina, French

publicists, and subsequently politicians, declared that their government

alone among the Western states had a special mission to civilize the

indigenous peoples now coming under its control -- what the French

called their mission civilisatrice.

have

celebrated the achievements of their own ever since. At no point in

modern history, however, did the French make more claims for their

civilization than during the new imperialism of the Third Republic. Of

course all European powers at the end of the nineteenth century claimed

to be carrying out the work of civilization in their overseas

territories; but only in republican France was this claim elevated to

the realm of official imperial doctrine. From about 1870, when France

began to enlarge its holdings in Africa and Indochina, French

publicists, and subsequently politicians, declared that their government

alone among the Western states had a special mission to civilize the

indigenous peoples now coming under its control -- what the French

called their mission civilisatrice.

This idea of a secular mission

civilisatrice did not

originate under the Third Republic; it nevertheless acquired a

particularly strong resonance after the return of democratic

institutions in France, as the new regime struggled to reconcile its

aggressive imperialism with its republican ideals. The notion of a

civilizing mission rested upon certain fundamental assumptions about the

superiority of French culture and the perfectibility of humankind.

It implied that France’s colonial subjects were to primitive to

rule themselves, but were capable of being uplifted.

It intimated that the French were

particularly suited, by temperament and by virtue of both their

revolutionary past and the4ier current industrial strength, to carry out

this task. Last but not

least, it assumed that the Third Republic had a duty and a right to

remake “primitive” cultures along lines inspired by the cultural,

political, and economic development of France.

The ideology of the civilizing mission could not

but strike a responsive chord in a nation now publicly committed to

institutionalizing the universal principles of 1789. At the end of the

nineteenth century, few French citizens doubted that the French were

materially and morally superior to -- and that they lived in greater

freedom than-the rest of the earth's inhabitants. Many may have scoffed

at the idea that the Republic's empire was actually bestowing these

blessings upon those ostensibly still oppressed. But no one questioned

the premise of French superiority upon which the empire rested, or even

that the civilizing mission could in fact be accomplished. Such

convictions were part of what it meant to be French and republican in

this period, and had a profound impact on the way in which the French

ran their colonies. Administrators

-- vastly outnumbered, and equipped with little more than their

prejudices -- relied upon the familiar categories of "civilization" and

its inevitable opposite, "barbarism," to justify and maintain their

hegemony overseas. These

categories served to structure how officials thought about themselves as

rulers and the people whom they ruled, with complex and often

contradictory consequences for French colonial policy -- and French

republican identity --in the twentieth century.