Roger Shattuck, The Banquet Years (1) -- La belle époque (The Good Old Days)

The French call it la belle époque -- thegood old days. The thirty years of peace, prosperity, and internal dissension which lie across 1900 wear a bright, almost blatant color. We feel a greater nostalgia looking back that short distance than we do looking back twenty centuries to antiquity. And there is reason. Those years are the lively childhood of our era; already we see their gaiety and sadness transfigured.

For Paris they were the Banquet Years. The banquet had become the supreme rite. The cultural capital of the world, which set fashions in dress, the arts, and the pleasures of life, celebrated its vitality over a long table laden with food and wine. Part of the secret of the period lies no deeper than this surface aspect. Upper-class leisure- the result not of shorter working hours but of no working hours at all for property holders--produced a life of pompous display, frivolity, hypocrisy, cultivated taste, and relaxed morals. The only barrier to rampant adultery was the whalebone corset; many an errant wife, when she returned to face her waiting coachman, had to hide under her coat the bundle of underga1ments which her lover had not been dexterous enough to lace back around her torso. Bourgeois meals reached such proportions that an intermission had to be introduced in the form of a sherbet course between the two fowl dishes. The untaxed rich lived in shameless luxury and systematically brutalized le peuple with venal journalism, inspiring promises of progress and expanding empire, and cheap absinthe.

Jean Beraud, The Wedding Reception (c.1900)

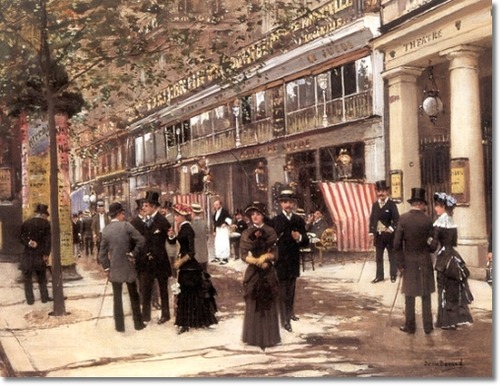

Jean Beraud, The Boulevard Montmartre and the Theatre des Varietes (c1886)

Politics in la belle époque found a surprisingly stable balance between corruption, passion ate conviction, and low comedy. The handsome and popular Prince of Wales neglected the attractions of London to spend his evenings entertaining in Maxim's restaurant, and he did not entirely change his ways upon becoming Edward VII. It was the era of gaslights and horse-drawn omnibuses, of the Moulin Rouge and the Folies Bergère, of cordon-bleu cooking and demonstrating feminists. The waiters in Paris cafes had the courage to strike for the right to grow beards; you were not a man or a republican without one at the turn of the century. Artists sensed that their generation promised both an end and a beginning. No other equally brief period of history has seen the rise and fall of so many schools of cliques and isms. Amid this turmoil, the fashionable salon declined after a last abortive flourishing. The cafe came in to its own, political unrest encouraged innovation in the arts, and society squandered its last vestiges of aristocracy. The twentieth century could not wait fifteen years for a  round number; it was born, yelling, in 1885. It all started with a wake and funeral such as Paris had never staged even for royalty. In May, 1885, four months after an immense state banquet to celebrate his eighty-third birthday, Victor Hugo died. He left the following will: "I give fifty thousand francs to the poor. I desire to be carried to the cemetery in one of their hearses. I refuse the prayers of all churches. I ask for a prayer from all living souls. I believe in God. Four years earlier, during public celebrations of his eightieth year of vigor, the Avenue d'Eylau, where he lived, had been officially renamed in his honor. Now his remains lay in state for twenty-four hours on top of a mammoth urn which filled the Arc de Triomphe and was guarded in half-hour shifts by young children in Grecian vestments. As darkness approached, the festive crowd could no longer contain itself. "The night of May 31, 1885, night of vertiginous dreams, dissolute and pathetic, in which Paris was filled with the aromas of its love for a relic. Perhaps the great city was trying to recover its loss. . . How many women gave themselves to lovers, to strangers, with a burning fury to become mothers of immortals!" What the novelist Barres here describes (in a chapter of Les déracinés entitled "The Public Virtue of a Corpse") happened publicly within a few yards of Hugo's apotheosis. The endless procession across Paris the next day included several brass bands, every political and literary figure of the day, speeches, numerous deaths in the press of the crowd, and final entombment in the Pantheon. The church had to be specially unconsecrated for the occasion. By this orgiastic ceremony France unburdened itself of a man, a literary movement, and a century.

round number; it was born, yelling, in 1885. It all started with a wake and funeral such as Paris had never staged even for royalty. In May, 1885, four months after an immense state banquet to celebrate his eighty-third birthday, Victor Hugo died. He left the following will: "I give fifty thousand francs to the poor. I desire to be carried to the cemetery in one of their hearses. I refuse the prayers of all churches. I ask for a prayer from all living souls. I believe in God. Four years earlier, during public celebrations of his eightieth year of vigor, the Avenue d'Eylau, where he lived, had been officially renamed in his honor. Now his remains lay in state for twenty-four hours on top of a mammoth urn which filled the Arc de Triomphe and was guarded in half-hour shifts by young children in Grecian vestments. As darkness approached, the festive crowd could no longer contain itself. "The night of May 31, 1885, night of vertiginous dreams, dissolute and pathetic, in which Paris was filled with the aromas of its love for a relic. Perhaps the great city was trying to recover its loss. . . How many women gave themselves to lovers, to strangers, with a burning fury to become mothers of immortals!" What the novelist Barres here describes (in a chapter of Les déracinés entitled "The Public Virtue of a Corpse") happened publicly within a few yards of Hugo's apotheosis. The endless procession across Paris the next day included several brass bands, every political and literary figure of the day, speeches, numerous deaths in the press of the crowd, and final entombment in the Pantheon. The church had to be specially unconsecrated for the occasion. By this orgiastic ceremony France unburdened itself of a man, a literary movement, and a century.