Karen Offen, “Women, Citizenship, and Suffrage in France Since 1789”

French women obtained the vote just over fifty years ago, in 1944-1945. As the French political scientist Janine Mossuz-Lavau recently remarked, "France is one of the last countries in Europe to have accorded women the right to vote and to run for office (éligibilité), just before Italy, Belgium,

Greece, Cyprus, Switzerland , and Liechtenstein." The American historian of French suffragism [i.e. of the right to vote], Steven C. Hause, framed the French case in even broader world comparative terms, again underscoring the astonishing backwardness of a nation whose leaders portrayed it as the vanguard of civilization: "By the 1930s, while the French Senate stood intransigent, women were voting in Palestine, parts of China, and several Latin American republics. Women voted in Estonia, Azerbaijan, Trans-Jordan and Kenya but not in the land of Jeanne d 'Arc [Joan of Arc] and the Declaration of the Rights of Man." After World War I, suffragist advocate Cecile Brunschvicg posed the issue in terms of national honor: "It is humiliating to think that we are Frenchwomen, daughters of the land of the Revolution, and that in the year of grace 1919 we are still reduced to demanding the 'rights of woman."'

How can this be? Paradoxically, the issue of votes for women (not to mention their eligibility for office) was articulated earlier in France than in virtually any other nation in the world -- in 1789, at the outset of the mighty French Revolution. Moreover, in 1848 France became the first major nation in Europe to institute universal manhood suffrage without property qualifications -- that is, for male individuals. Following enactment of Napoleon's Civil Code of 1804, a law code whose provisions (including those that subordinated women in marriage) were imitated throughout Europe, France became the site of perhaps the most radical and thoroughgoing critique of women's subordination in all Europe; by the 1890s, French women's rights activists had launched the term feminisme throughout the world. Thus this long delay in according the vote to women seems startling, a dissonant historical fact that cries out for explanation. . . .

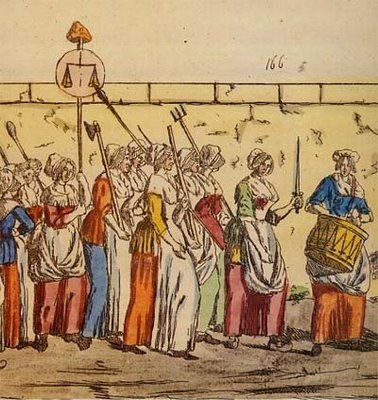

Women in the French Revolution

WHAT WAS REQUIRED TO ACHIEVE WOMAN SUFFRAGE IN FRANCE? (1848-1910)

The demand for woman suffrage arose again in the later 1860s, framed as an issue of political rights (droits politiques). This time, the French debate resonated with the contemporaneous debates in Britain (following introduction of the Second Reform Bill in March 1865) and the United States . . .

This phase of the French campaign for woman suffrage was spearheaded by Julie-Victoire Daubie, who revived the case for single adult women's suffrage, first in her book-length study La Femme pauvre, then in L'Emancipation de Ia femme en dix livraisons (1871 ). Daubie's crusade was accompanied by an extended debate on the issue of women's political rights within the Paris Law School, capped by Professor Alexandre Duverger's decisive conclusion against giving the vote to women on the grounds that previous instances of women meddling in French political life had proved pernicious! No one suggested that French women were nor capable of exercising the suffrage; instead, opponents implied that letting them do so was simply inopportune, inappropriate, or alternatively, dangerous!

The political context changed abruptly, however, following the sudden defeat of French armies by Germany in late 1870, the collapse of the Second Empire, the occupation of Paris, the Commune, and the founding of the Third Republic. With the election of a new National Assembly in 1871, in which republicans were very little represented, ambivalence about the practice of universal suffrage by men continued to cloud further discussion of the woman suffrage issue; such ambivalence would plague advocates of women's vote throughout the French Third Republic.

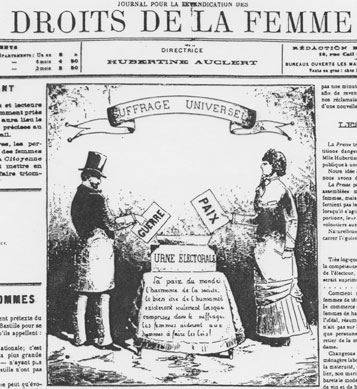

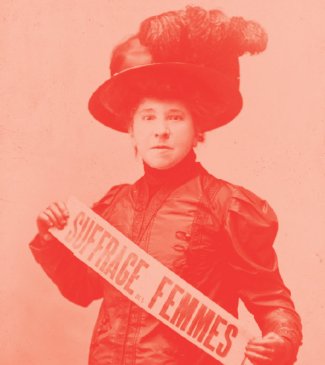

In the mid-1870s freedoms of the press and association (opened up briefly during the late Second Empire) were again sharply curtailed. Seriously compounding the political situation was the severe polarization of partisan political life between anticlerical republicans and monarchist Catholics. The former hesitated to champion woman suffrage for fear that women would support the monarchist Catholic factions that opposed the Republic. Even after 1880, when the republicans attained control of all branches of the new government, no major republican faction knew for certain just how women's votes might affect its fragile hold on power; both republicans and monarchists continued to insist on the significance of women's influence. The republicans established state secondary schools for girls to contest Catholic hegemony over women's education. With the notable exception of Hubertine Auclerr, who did spearhead a woman suffrage campaign from 1878 until her death in 1914, republican advocates of women's rights thought it best to postpone the suffrage question until the new and fragile Third Republic was more firmly established.

Hubertine Auclert, however, challenged French republicans to realize political equality for women as individuals, arguing that a republic in which women (including married women) were not considered full citizens was no "true" republic; she continued her campaign by founding a periodical provocatively entitled La Citoyenne [Female Citizen]. Such criticism was not welcome among republicans, for it confronted them squarely on the lack of inclusiveness of the very principles to which they subscribed! But the various republican factions, including the Radicals, resisted the implications of Auclert's charges. Before 1900 only the Socialists, who were very far from holding power and had little to lose, were willing to risk endorsing the principle of the female vote.

What was required to institute votes for women in Third Republic France? Literally, nothing more than a change of wording in a regime of textual law. The French electoral law of 1848 (and its 1884 amended version, the law of April 5) read: Tous les français [all the French]. This was equivocal, since in civil and penal law, the masculine form tous les français was deemed to encompass women. The British earlier, and before them the Americans in New Jersey (1807), had clarified the situation by stipulating "men," in line with the electoral laws of other states. In the 1860s England, John Stuart Mill proposed effecting the change by amending the term "men" to read "persons," which would include women. Could the same tactic be applied in France? The elasticity of tous les français was tested several rimes in court by small groups of women and their male supporters. In 1885, two women, Louise Barbarousse and Marie Richard Picot, attempted to register to vote under the new electoral law of 1884; the Paris Municipal Council denied their request, and their appeal was heard by a justice of the peace. Two male lawyers, Jules Allix and Leon Giraud, represented their case, pleading on the high ground of "imprescriptable rights" of the individual as well as national prestige that women should vote in France:

It is necessary to the glory of the French laws that they leave a place to woman in this sphere of public power, and it will be to the honour of the declaration of the rights of man to acknowledge also the rights of woman.... Does not tous les français encompass every individual of the French nationality, without exception of sex?

The judge handed down his denial of the appeal, framed in terms of legal- historical precedent that dodged the issue of principle. Even issues of grammatical gender were freighted with contextual precedent. Judge Carre insisted that since the Revolution, voting citizens had been males only; indeed the Constitutions of June 1793 and August 1795 had expressly spelled out this point. He noted further that the most recent laws stipulate that "in order to be an elector, one must be a citizen" and that "the citizen is the Frenchman who has full political and civil rights"; therefore since women have neither, and are therefore not citizens, they cannot be electors. In concluding, however, the judge abandoned his air of juridical neutrality:

Whereas, finally, if women repudiating their privileges and inspiring themselves with certain modern theories, believe the hour has come to break the bonds of tutelage with which tradition, law, and custom have surrounded them, they must bring their claim before the Legislative power, and not before the Courts of Law.

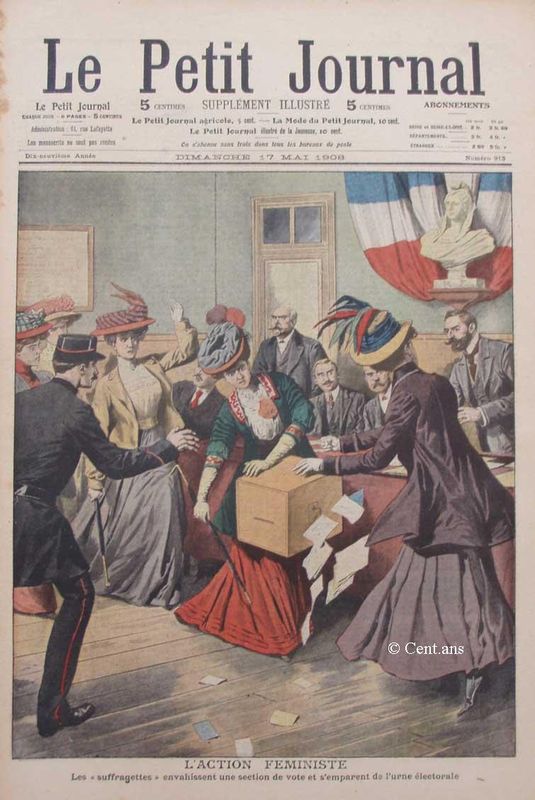

An intriguing aspect of the subsequent French suffrage campaign was the mobilization of historic precedent on the side of women's citizenship and women's suffrage, and the way in which it was done. An important contribution to this effort was Leon Giraud's study on the comparative status of women with respect to public and political rights, which won a prize from the Paris Law Faculty in 1891. Giraud shared the prize with a widely translated treatise by Moïse Osrrogorski, who had argued that the question of determining who would vote was a political question above all else. With such scholarship at hand, feminists such as Eliska Vincent again attempted to register to vote, while Hubertine Auclerr reminded her readers (and their legislators) of women's participation in political life during the ancien regime [the period before the French Revolution began in 1789]. These advocates of woman suffrage insisted, on the basis of incontrovertible evidence, that women had repeatedly voted in earlier periods of French history, when votes were tied to fiefs or landed property, not to individuals. The Rennes judge Raoul de Ia Grasserie argued for woman suffrage in the Revue politique et parlementaire (1894) in terms reminiscent of those used over a century earlier by Condorcet: "Half humankind is not represented in the vario s parliamentary assemblies; the laws are made without her and often against her." Her sex places her outside the class structure; "the worker, the most illiterate peasant have that choice [to select their representatives], and the most intelligent, most experienced women cannot.... She cannot eve n choose among those of the opposite sex who will be her masters." The judge went on to advocate (in principle) that women be permitted to run for office as well -- but not right away. But the measure must and inevitably would come. Woman su frage was, in Grasserie's eyes, a question of social justice.

In fact, the 1890s witnessed a tremendous outburst of public debate over the woman question, and Hubertine Auclert's term feminisme became common currency to describe the burgeoning movement for women's emancipation. Despite the visibility of the issues -- reform of women's situation in the Civil Code, including married women's property rights; demands for women's right to work and equal pay; issues surrounding maternity and sexuality -- few of the numerous civil and economic reforms advocated by and for women were realized. Male legislators seemed more absorbed in protecting -- and controlling women than in emancipating them, in spite of the valiant efforts by Julie Victoire Daubie, Hubertine Auclert, and their allies to place the suffrage question before the lawmakers. It was only after 1900 that woman suffrage arrived on the agenda of the Chamber of Deputies.

When, in 1900, the reformer and newspaperwoman Marguerite Durand convened an international congress on women's rights in Paris, the suffrage question occupied a prominent place. By this time many members of the new generation of women's movement leaders had come around to the position long asserted by Auclert; they now agreed that the main reason why substantive and sensible reforms in the laws governing women's situation were not forthcoming was because women bad no political power. As Rene Viviani, deputy and future prime minister of France, declared to the assembled delegates at the women's rights congress: "In the name of my relatively long political and parliamentary experience, let me tell you that the legislators make the laws for those who make the legislators." There was no getting around it women must have the vote in order to realize the feminist program.