Masculinity and the Dreyfus Affair

Robert A. Nye, “Masculinities in War and Peace,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 112, No. 2 (Apr., 2007), pp. 417-438.

In this review of literature on masculinity, historian Robert Nye describes how the battle over the guilt of innocence of Army Captain Alfred Dreyfus became involved with the development of late 19th century French notions of what men should be like. Each side tried to appeal to aggressive notions of masculinity and homophobia to make their case. We will delve into the Dreyfus affair in more depth later in the course, but the details are not necessary to understand historians' arguments about how image of the ideal male were changing.

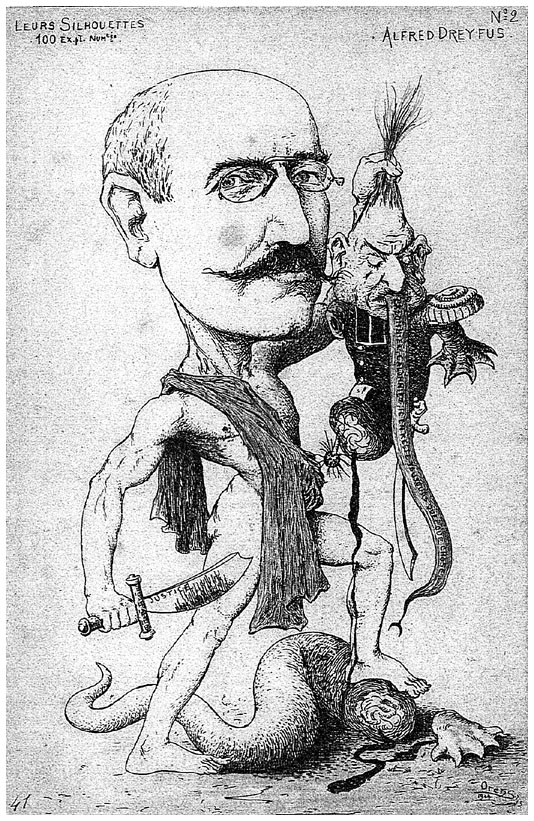

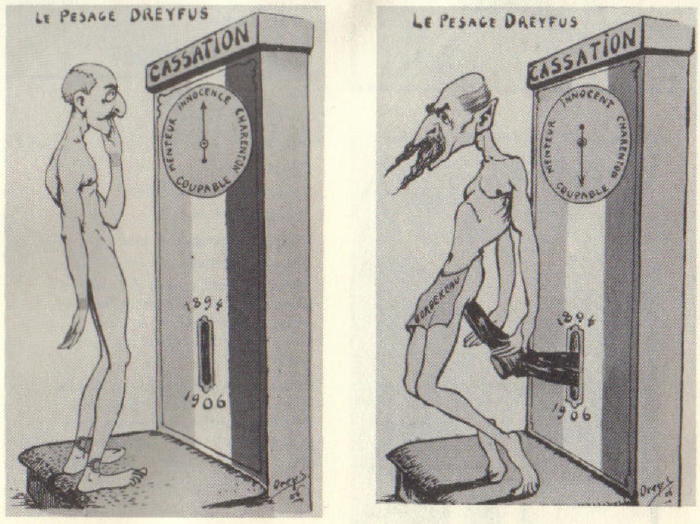

France experienced a similar fin-de-siecle [“end of the century” – in this case, the end of the 19th century] fascination with sport and physical culture. Pierre de Coubertin was the moving force behind the reestablishment of the Olympic Games in 1896, and the brutalizing rigors of the Tour de France bicycle race began just after the turn of the century. The biggest games in town, however, were the body wars of the Dreyfus Affair, which convulsed France in these same years. Christopher Forth has written a fascinating account of the struggle between antiDreyfusards and Dreyfusards for the privileged heights of masculine superiority. As was the case elsewhere, many French pundits were worried about the effeminizing effects of modern consumer culture, but they also feared the debilitating effects on young men of France's intensely competitive intellectual culture. Dreyfus's detractors used the interarticulated "others" of race and gender to make the body of Dreyfus into an effeminate, cowardly, and abject exemplar of a man, and those of his defenders into limp, unmanly homo sedentarius. Intellectualized Jews, pacifists, and socialists were the perfect foils, Forth reminds us, for the image of military manhood adopted by the apologists for the French Army.

The Dreyfusards fought back with similarly gendered and sexualized hyperbole. They claimed to be heroes of thought, fearless in their moral courage, and seekers after truth. Dreyfus himself and Emile Zola, forced into exile in England, were portrayed in religious imagery as sacrificial beings offering up their suffering bodies to the irrational anti-Dreyfusard crowd. Each side made insinuations about the homosexuality of the other, duels broke out between respective "champions," and women were brought onto the stage as moral exemplars and symbols of truth, but usually as incarnations of bodily frailty under the protection of gallant men. The Dreyfusards may have enjoyed a short-lived political triumph and won the symbolic victories in the Affair, but the real winner in this great political crisis was a discourse of military masculinity and a culture of the muscular, intrepid male body. By 1913, the new term "intellectual" had become an insult, and that bastion of intellectualism, the Ecole Normale Superieure, a "barracks." The "culture of force" was celebrated everywhere as a physical manifestation of strength and a moral force of will. The soldier in the citizen was primed to emerge. As George L. Mosse has taught us, by the end of the nineteenth century the male body had come to represent the health and well-being of the body politic.

Image by Supporters of Dreyfus

|

Image by Opponent of Dreyfus  |