David H. Pinkney, Napoleon III and the rebuilding of Paris (4)

Paris Before Haussmann -- Sanitation

Certainly an inconvenient city, Paris of 1850 was also a smelly city. Perfumery was not a major business for no reason. The crowding together of tenements with factories and shops produced a concentration of industrial and domestic odors in areas where air could not easily penetrate to disperse them. The droppings of the city's 37,000 horses, removed only once a day, and the garbage nightly piled on the street for collection added to the city's odors, but the principal assault upon the Parisian's nostrils must have come from the sewers, the gutters that substituted for them on many streets, and the cesspools and carts used in the disposal of human excrement.26

The city had built its sewers over the course of centuries, adding to them bit by bit to satisfy the immediate needs of

La Bievre A river, running through the Left Bank, turned into an Industrial Waste Dump by the 16th century |

the time. In the course of the first half of the nineteenth century successive administrations made many improvements: they extended the total length of the system more than five-fold and nearly completed the centuries-old project of enclosing the principal sewers, but in 1850 the system was still shockingly inadequate

for a growing city of one million inhabitants. The three principal collector-sewers were still those used in the Middle Ages: the Seine River itself, the Biévre River on the Left Bank, and the ancient stream of Ménilmontant (called the Ceinture Sewer), running eastward from Ménilmontant between the inner boulevards and the octroi wall to the Seine at Chaillot. The latter two were enclosed, but, of course, the Seine, which received the discharge of the other two collectors and of a number of smaller sewers as well, lay open both to sight and to smell. A manual system of removing toilet sewage spared the river the city's human excreta, but pollution came from the wastes of households and shops, and the seepage of cesspools and cemeteries. Ordinarily the flow of the river assured self-purification quickly enough to avoid serious offense and to prevent any menace to health as long as the river was not used for water supply.26 Nevertheless, a speaker in the Legislative Body near the end of the Empire recalled with distaste "the black torrents" that two decades earlier poured into the river from sewers under the Pont Neuf, the Pont Royal, and the Pont de la Concorde.27 Zola watching the river near the Pont Royal in those days saw "the surface... covered with greasy matter, old corks and vegetable parings, heaps of filth....28

The Seine was not the only sewer disguising under a different name. Two-thirds of the city's streets ran with the waste water of the adjacent shops and houses, for despite the extension of the sewer system since the Revolution, Paris had in 1851 only eighty-two miles of underground sewers to serve more than 250 miles of streets.29 Most streets still depended on streams in the gutters to carry rain and waste water to the nearest underground sewer. At best these waters were unsightly and gave off a slight odor. When allowed to stand for twenty-four hours, as they might if caught in a depression of a gutter, or when they included liquid excreta, which were permitted in the gutters after 185o, they emitted a nauseating odor.30 In the covered sewers the excreta hastened fermentation, making worse the noxious smell issuing from the openings, despite twice weekly cleanings. Rains caused the gutters to overflow, spilling their contents into cellars, courtyards, and vestibules of neighboring buildings. . . .

The method of removing human excrement seemingly might have been designed to spread bad odors. Each proprietor provided a cesspool in the form of a masonry ditch or some less satisfactory receptacle in which his tenants deposited this sewage, and each night some 200 carts overran the sleeping city to collect the contents of filled ditches. When the carts were loaded to overflowing they made their dripping way to La Villette, where a pump, supplemented by canal boats, awaited to move the vile smelling mass on to a disposal plant in the Forest of Bondy, six miles to the east of Paris. Not until 1849 was disinfection of the household ditches made obligatory, and even then the process used failed to neutralize the bad odors, nor did covers confine them. They spread through streets and houses, and at night the heavy wheels of the carts bumping over the cobblestones awakened Parisians so that they might not miss the revolting smell broadcast by the leaking wagons.82

Sewage disposal and water supply are ever closely related problems, and in Paris a century ago there was one shockingly direct connection. The city drew part of its water supply from that main collector sewer, the Seine, and pumped it largely at points downstream from the mouths of sewers emptying into the river. Most of the remainder of the city's water supply came from sources little more inviting. . . .

Only one house in five had water piped to it, and in all Paris fewer than 150 houses had running water above the first floor. This niggardly equipment was not owing alone to the stinginess of Parisian landlords. A quarter of the city's streets had no water conduits, and where water was available the uncertainty of supply must have repelled customers. In the summer when demand was heavy the customer could frequently get only a trickle from his water tap, because most of the secondary distribution pipes were so small that they emptied more quickly than they could be refilled, even though the reservoirs were full. In the winter flow was frequently cut off by freezing of water in pipes laid too close to the surface.34 . . . .

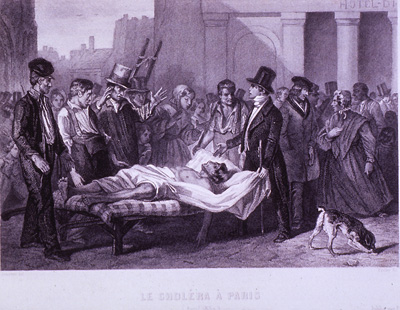

In the first half of the nineteenth century Paris had suffered two fearful epidemics. Cholera, a pestilence unknown or unidentified in the West before the 1830's, had moved westward out of India in the preceding decade and descended on Europe in 1831. In Paris it attacked 39,000 persons and killed 18,400 of them, including the Prime Minister himself. It struck again across Europe in 1848-49, and this time 19,000 Parisians died. Among medical men a great controversy had raged between the contagionists and the anti-contagionists over the means of transfer of this and other epidemic diseases, but by the time of the second epidemic the anti-contagionist view was generally accepted in France and in Britain and Germany as well. Although subsequently proved erroneous, its influence was salutary, for the anti-contagionists believed that cholera arose from local causes: accumulations of filth, over-crowding, lack of air and light, faulty drainage, infected sewers, polluted water, unwholesome food; and this belief tended to turn attention away from usually fruitless quarantines at frontiers, to efforts to remedy the evil within. The two great epidemics aroused popular and official alarm, and the anti-contagionist theory directed it toward problems of public hygiene. In the teeming slums of Paris and in the sewers and water supply it found abuses crying for reform.88

In the first half of the nineteenth century Paris had suffered two fearful epidemics. Cholera, a pestilence unknown or unidentified in the West before the 1830's, had moved westward out of India in the preceding decade and descended on Europe in 1831. In Paris it attacked 39,000 persons and killed 18,400 of them, including the Prime Minister himself. It struck again across Europe in 1848-49, and this time 19,000 Parisians died. Among medical men a great controversy had raged between the contagionists and the anti-contagionists over the means of transfer of this and other epidemic diseases, but by the time of the second epidemic the anti-contagionist view was generally accepted in France and in Britain and Germany as well. Although subsequently proved erroneous, its influence was salutary, for the anti-contagionists believed that cholera arose from local causes: accumulations of filth, over-crowding, lack of air and light, faulty drainage, infected sewers, polluted water, unwholesome food; and this belief tended to turn attention away from usually fruitless quarantines at frontiers, to efforts to remedy the evil within. The two great epidemics aroused popular and official alarm, and the anti-contagionist theory directed it toward problems of public hygiene. In the teeming slums of Paris and in the sewers and water supply it found abuses crying for reform.88

Americans forever puzzling over why Frenchmen behave so oddly like Frenchmen can find in Paris of a century ago another paradox wanting explanation. Here were the highly civilized and reputedly luxury-loving Parisians tolerating the inconveniences and hazards of an overgrown medieval city: alley-like streets without issue, slums without light and air, houses without water, boulevards without trees, crowding unrelieved by parks, and sewers spreading noxious odors. The needs of the city were apparent, and the daily congestion of traffic, the death rate (the highest in France), the two great cholera epidemics proclaimed them for all to see. Successive administrations had made efforts to meet them-a new street there, a passageway widened here, new sidewalks, more sewers, a few thousand gallons added to the city's water supply, but their efforts had been fragmentary. They had lacked the courage, the imagination, and the temerity to attack the staggering problem of virtually rebuilding the city, and if Paris were to support a growing population without peril to public order and public health, nothing less would suffice.