David H. Pinkney, Napoleon III and the rebuilding of Paris (3)

Paris Before Haussmann -- Circulation

The toll bridges had handicapped free movement between the two banks, but they were minor obstacles to traffic

Crowded and Muddy Streets of 18th Century Paris |

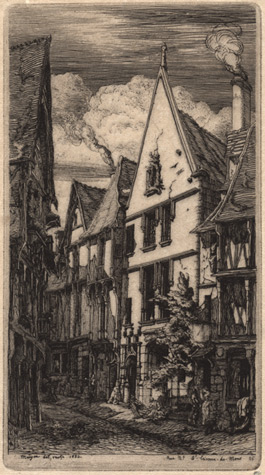

compared with the medieval street system. Evolved in a city of a few tens of thousands, for pedestrians, sedan chairs, and horsemen, it was ill-suited for the carriages and wagons of a city of one million inhabitants. Except on the boulevards or along the quais, which offered only circuitous routes to most traffic, one could not on the Right Bank travel directly across the city from east to west. The Louvre, the Palais Royal, and the Bibliothbque Nationale lay like a long barricade athwart the western end of the inner city, and the maze of ancient streets and houses just to the east formed a second and broader barrier. . . .

On the Left Bank traffic was no better served. From L'Institut de France to the Pont d'Austerlitz no adequately broad thoroughfare cut southward through the heavily settled belt along the river. The Luxembourg Garden, the hill of SainteGenevieve, and the Jardin des Plantes were obstacles to traffic, and the streets that ran through the gaps were in some places scarcely wide enough to permit the passage of two wagons side by side. Other streets in the Latin Quarter were little better than culs de sac . . .

The confused street pattern made even a short trip across the city a complex journey. Baron Haussmann, who as Prefect of the Seine later carried out Napoleon III's transformation of Paris, described the tortuous route he followed in his student days in the 1830's from his home on the Right Bank to the School of Law in the Latin Quarter:

Setting out at seven o'clock in the morning from the quarter of the Chaussée d'Antin, where I lived with my family, I reached first, after many detours, the Rue Montmartre and the Pointe SainteEustache; I crossed the square of the Halles, then open to the sky, among the great red umbrellas of the fish dealers; then the rues des Lavandi.res, Saint-Honor6 and Saint-Denis;... I crossed the old Pont au Change, which I was later to rebuild, lower, widen; I next walked along the ancient Palais de Justice, having on my left the filthy mass of pot-houses that not long ago disfigured the Cite.... Continuing my route by the Pont Saint-Michel, I had to cross the poor little square [Place Saint-Michel].... Finally I entered into the meanders of the Rue de la Harpe to ascend the Montagne Sainte-Genevieve and to arrive by the passage de l'Hôtel d'Harcourt, the Rue des Maqons-Sorbonne, the Place Richelieu, the Rue de Cluny and the Rue des Gres, on the Place du Pantheon at the corner of the School of Law.22

Haussmann's long daily trek from home to work was, however, unusual in the Paris of his youth and even later. Parisiansof a century ago ordinarily lived, worked, and found their pleasures within the confines of a few blocks, having yet to acquire that "dizzying idea" that Jules Romains noted among Parisians of the twentieth century that "they could move about just as they liked and that distance was the last thing that counted." Balzac's Jules and Sylvia Rogron living in Paris in the 1820's knew nothing of the city beyond their own street, and even a substantial citizen like CUsar Birotteau in the normal routine of his life as businessman, deputy mayor, and judge never went beyond the inner boulevards and only rarely crossed the river.

Haussmann's long daily trek from home to work was, however, unusual in the Paris of his youth and even later. Parisiansof a century ago ordinarily lived, worked, and found their pleasures within the confines of a few blocks, having yet to acquire that "dizzying idea" that Jules Romains noted among Parisians of the twentieth century that "they could move about just as they liked and that distance was the last thing that counted." Balzac's Jules and Sylvia Rogron living in Paris in the 1820's knew nothing of the city beyond their own street, and even a substantial citizen like CUsar Birotteau in the normal routine of his life as businessman, deputy mayor, and judge never went beyond the inner boulevards and only rarely crossed the river.

The next thirty years brought no change in common habits. Gervaise Macquart, the heroine of Zola's L'Assommoir, who came to Paris in 1850, lived first on the Boulevard de la Chapelle. After her marriage she moved to a lesser street nearby, later opened her laundry shop a few doors away, and when she had to give it up she took a room in the same building and lived there until her death in 1859. On only a few occasions did she leave the neighborhood. Following her marriage in the local mayor's office a member of the wedding party proposed a visit to the Louvre, and although they were all residents of Paris only one of the twelve in the party had ever been there, and their behavior on the walk to the Louvre and back betrayed that the center of Paris was strange to them.

Neither the wedding party nor Haussmann apparently ever considered taking a bus, although Paris had been served by public buses since 1828, and in 1850 had thirty lines (with fascinating names like Gazelles, Doves, and Reunited Women) and more than 300 buses. They were equipped, moreover, with cushioned seats, and every passenger was assured of one, for once all the places were filled no more riders were taken. But old habits were not likely to be broken down while the fare remained at 30 centimes, about one-tenth of an ordinary worker's daily wage in 1850, and while fashionable Parisians would not be seen on the public buses. In 1856, the first year for which information is recorded, the average number of fares paid by each of the city's residents during the entire year was only thirty-nine.23

This localized existence, contrasting so oddly with urban life today, appears less strange when considered against the pattern of Paris' streets in 1850. Continued toleration of such a system of streets reflected perhaps a distaste for movement, but the streets themselves discouraged mobility. And it was not only their dimensions and their aimlessness that dismayed the traveler. They were paved with nine inch cubes of sandstone whose edges quickly crumbled under constant wear and produced a surface that was jolting and noisy and offered an uncertain footing for pedestrians and horses alike. The slightest rain turned the dirt from the paving sand into black mud. Although the administration under the July Monarchy had built sidewalks along most streets, the pedestrian on the narrow ways often had to depend on the hospitality of shop doors to avoid being run down or splattered with mud and the filthy water that flowed in the gutters. In the winter when this water froze, ice was an added hazard. By night the streets were little inviting either to carriages or to pedestrians. During six months of the year some 12,000 gas lamps and 1,600 surviving oil lanterns were lighted nightly along the streets. During the remainder of the year only a fraction of them was used and for only part of the night. The permanently fixed gas lights installed during the July Monarchy were an improvement over the oil lamps that swayed like ships' lanterns on ropes hung across the streets, but even they cast little light on the streets.24