Howard Saalman, Haussmann: Paris Transformed

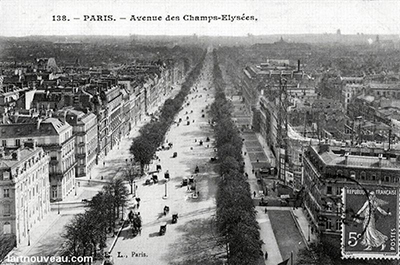

These streets [created by Haussmann] had a two-fold character: They existed both for their own sakes, as places to live and shop according to new standards of upper middle class affluence, as a kind of stage for elegant living, promenading, and socializing in outdoor cafés and restaurants, and also as connecting corridors between what an up-to-date mid-nineteenth century man such as Napoleon III considered key points of the city. As links the streets functioned in two directions: They provided rapid access from the railway stations at the city’s periphery to the key points at the center (government buildings, central markets, hospitals, business and entertainment districts), and in turn linked the central organs of administration and business (fire department, riot police, ambulance service, department store deliveries) with the focal points of the city’s various quarters. The intersections of two or more such arteries would clearly become major nodes of traffic and urban activity. . .

Demolition for the Rue de Rennnes

tasks of his day to a limited number of clearly defined projects capable of realization. His success in carrying out the imperial program for Paris would have been less if he or the government he served had been deeply concerned with catering to the wide variety of social, political, and cultural strata composing the nation. Such concern would have required nothing less than democratic give-and-take at all political levels, taking into account all the obstacles which the consequent political compromises would have posed to large-scale, single-minded solutions. Except for concessions to the Church in the form of publically supported denominational schools along with secular schools, the Empire neglected this political approach almost by definition. The new Paris visualized by Napoleon III and by Haussmann was to be first a city useful to the political interests that the Empire represented above all others, a city whose social ethos, combining economic liberalism with political conservatism, could be summed up: as much as possible for the people, as little as possible by the people. If the rapidly expanding economy fostered by the Empire provided a vast number of new jobs, thus keeping the peasants who were streaming to the cities content and off the barricades, so much the better. If social benefits in the form of an expanded public school system, extensive parks, new sewers and waterworks, improved health and recreational facilities, filtered down to the lower middle and working classes, no harm done. If trade unions (permitted in 1864) helped to keep industrial peace, so be it. But all of these benefits were part of an overall program geared primarily to the needs and objectives of the upper middle class in power.

tasks of his day to a limited number of clearly defined projects capable of realization. His success in carrying out the imperial program for Paris would have been less if he or the government he served had been deeply concerned with catering to the wide variety of social, political, and cultural strata composing the nation. Such concern would have required nothing less than democratic give-and-take at all political levels, taking into account all the obstacles which the consequent political compromises would have posed to large-scale, single-minded solutions. Except for concessions to the Church in the form of publically supported denominational schools along with secular schools, the Empire neglected this political approach almost by definition. The new Paris visualized by Napoleon III and by Haussmann was to be first a city useful to the political interests that the Empire represented above all others, a city whose social ethos, combining economic liberalism with political conservatism, could be summed up: as much as possible for the people, as little as possible by the people. If the rapidly expanding economy fostered by the Empire provided a vast number of new jobs, thus keeping the peasants who were streaming to the cities content and off the barricades, so much the better. If social benefits in the form of an expanded public school system, extensive parks, new sewers and waterworks, improved health and recreational facilities, filtered down to the lower middle and working classes, no harm done. If trade unions (permitted in 1864) helped to keep industrial peace, so be it. But all of these benefits were part of an overall program geared primarily to the needs and objectives of the upper middle class in power.