Colin Jones, Paris: A History

Haussmannism and the City of Modernity

1851-89Strategies that Made Haussmannization Possible

Even before Haussmann was appointed Prefect, an imperial Commission for the Embellishment of Paris had already begun to devise plans for the renovation of the city which in many details prefigured Haussmann 's programme. Interior Minister Persigny was also developing similar ideas at the same time. These precursors may have had a scintillating vision of the modern city, however, but they lacked the political, financial and administrative clout to bring that vision to life. This is what Napoleon and Haussmann were able to provide -- albeit only from 1853 onwards. The plans of renewal which Napoleon tried out when he was still only president of the Republic, for example, had failed to make much impact. Haussmann's predecessor as Prefect of the Seine, Jean-Jacques Berger, regarded Napoleon's plans as overcasted: 'I'm certainly not going to be involved,' he noted privately, 'in the city's financial ruin. He proved a perennial wet blanket. Napoleon's seizure of Paris by coup d'etat in December 1851, however, and then his declaration of the Empire in November 1852, swung the balance of power his way. In Haussmann , whom he put in Berger's place in June I853, he found an energetic and committed political fixer, who was altogether more receptive to hi s ideas, and who was more than happy to strong-arm the municipal council -- whose members he personally appointed anyway -- into assenting to his master's wishes.

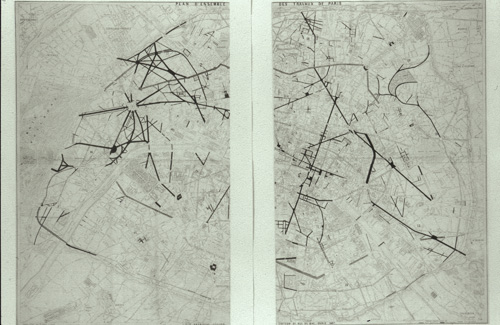

Haussmann's Map of the Streets to be Added to Paris

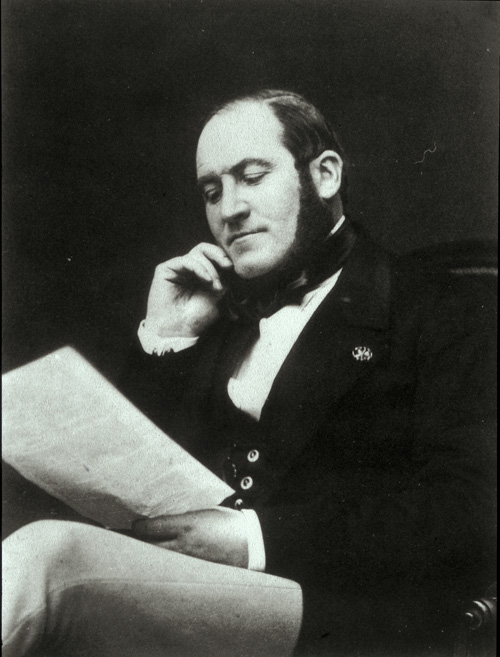

Photograph of Haussmann